I recently stumbled upon the following question on Quora:

I thought this was a fantastic question. It immediately got me thinking. I considered it a perfect opportunity to search for some lesser-known names in chess history and bring them to the fore.

I spent some time researching and pondering and I came up with 5 names. I was pretty proud of my choice and I thought this is a topic that is worth discussing and investigating further, so I decided to take the answer and post it here on Chessentials as well.

FIDE first introduced its titles (including the Grandmaster title in the 1950s. Initially, 27 top players got it – mainly the best players at a time and players still living who were among the best players in the world at some point during their careers.

However, FIDE didn’t award any titles posthumously, which means that many chess masters from the 19th century and the first half of the 20 century didn’t receive one.

And even though FIDE later introduced the honorary GM title, it was awarded only to two players posthumously – Rudolf Maric and Karoly Honfi.

This means that all the greats from the past – Morphy, Steinitz, Lasker, Capablanca, Alekhine – were never awarded one. These 5 World Champions are very obvious candidates, to begin with.

However, I think legacy is already so well-known that the question of whether they are actually holding a piece of paper is irrelevant. I think that, in the instance of these great players, GM title is completely superfluous – every chess schoolboy knows their name (and their games) as it is.

For me, personally, awarding the GM title posthumously should serve as a recognition of a player’s achievements and contributions to the game.

Considering that the World Champions’ achievements and contributions are already recognized, I’d ideally search for some forgotten names – players who achieved high level of chess mastery, but due to various circumstances never realized their full potential (and earned their GM title).

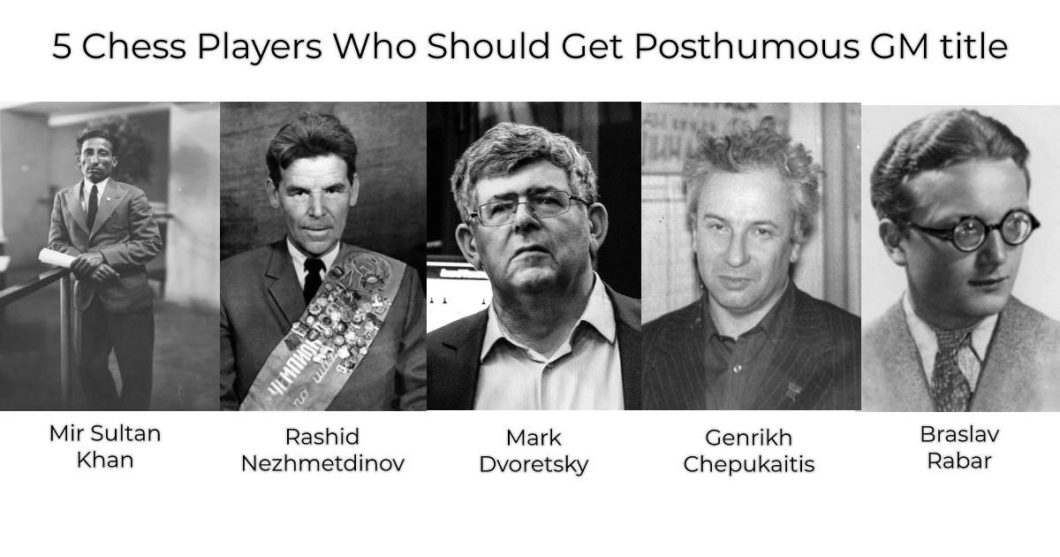

This was my guidance while assembling this list. Below you will find 5 players who never became GM, yet who clearly played at the GM level at some point in their life.

1. Mir Sultan Khan

Just yesterday, I wrote an answer about Anand’s legacy where I mentioned that he single-handedly rose from a country without a chess culture to become one of the world’s best players.

However, I completely forgot Anand had a predecessor. Mir Sultan Khan was a servant from British India owned (I guess) by colonel Nawab Sir Umar Hayat Khan. He learned chess from his father at a young age and quickly became the strongest player in his region.

In 1929, sir Umar traveled to Britan with Sultan Khan (since my main reference at this point is Wikipedia, I am not sure if Umar actually took Sultan Khan to play in the tournament as hinted there).

In any case, Sultan started competing in tournaments and, despite initial bad results, became the British Champion.

Then, after a brief return to India, he came back stronger than ever and in the 1930–1935 period, competed successfully in International tournaments, played on the first board in several Olympiads with good results and played en par with the best players in the world.

Alas, after this, his master decided to return to India, Sultan Khan went with him and virtually never played chess again. This quote from the pen of Reuben Fine (taken from Wikipedia) is the best evidence of how circumstances affected potentially great careers:

The story of the Indian Sultan Khan turned out to be a most unusual one. The “Sultan” was not the term of status that we supposed it to be; it was merely a first name. In fact, Sultan Khan was actually a kind of serf on the estate of a maharajah when his chess genius was discovered. He spoke English poorly, and kept score in Hindustani. It was said that he could not even read the European notations.

After the tournament [the 1933 Folkestone Olympiad] the American team was invited to the home of Sultan Khan’s master in London. When we were ushered in we were greeted by the maharajah with the remark, “It is an honor for you to be here; ordinarily I converse only with my greyhounds.” Although he was a Mohammedan, the maharajah had been granted special permission to drink intoxicating beverages, and he made liberal use of this dispensation. He presented us with a four-page printed biography telling of his life and exploits; so far as we could see his greatest achievement was to have been born a maharajah. In the meantime Sultan Khan, who was our real entrée to his presence, was treated as a servant by the maharajah (which in fact he was according to Indian law), and we found ourselves in the peculiar position of being waited on at table by a chess grand master.

Unfortunately, when FIDE introduced the GM title, he was never awarded one:

In 1950, when FIDE first awarded the titles of International Grandmaster and International Master Sultan Khan had not played for 15 years. Although FIDE awarded titles to some long-retired players who had distinguished careers earlier in their lives, such as Rubinstein and Carlos Torre it never awarded any title to Sultan Khan.

I, therefore, think, Sultan Khan is an ideal candidate for a posthumous GM title.

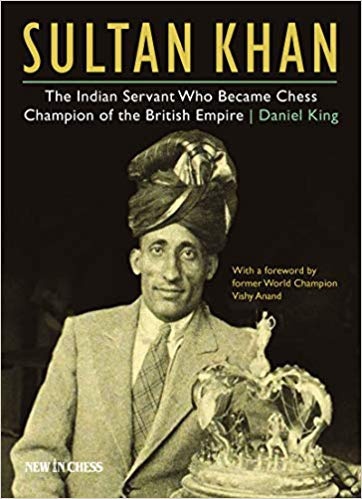

P.S. As I was writing this, I realized I don’t know much about Sultan Khan’s life, apart from the Internet sources (which should be always taken with a grain of salt). Incidentally, there is a biographical book about Sultan Khan’s life and games, written by Daniel King, which will be published on 15th April 2020. Can’t wait:

2. Braslav Rabar

Braslav Rabar’s name will maybe not be very familiar to the international audience, but his name is rather well known among the chess aficionados in Croatia, as he was one of the strongest Yugoslav players in the 1940s and 1950s.

Among other things, his achievements include:

- Yugoslav Champion 1951

- Qualified for the 1954 Interzonal Tournament in Göteborg

- Team gold medal and individual gold medal on fourth board (+8–0=2) at the Olympiad in Dubrovnik, 1950

- Team bronze medal and individual bronze medal on second board (+5–1=6) at the Olympiad in Helsinki, 1952

- Team bronze medal at the Olympiad in Amsterdam, 1954

It has to be said he was never a chess professional as he worked as a journalist at the Yugoslav television his entire life.

Apart from his playing achievements, he was a big chess publicist, the editor of the legendary Chess Informant and the inventor of the ECO opening system classification.

Despite all this, he was “only” awarded the title of International Master in 1950.

Back in the day, getting a GM title was much, much harder than nowadays.

I think that granting a posthumous GM title would be a great recognition of Rabar’s contribution to our game.

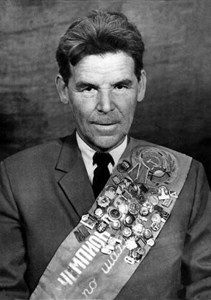

3. Rashid Gibiatovich Nezhmetdinov

When it comes to the players deserving of GM title yet never obtaining it, Rashid Gibiatovich Nezhmetdinov is arguably the name that first comes across your mind.

This brilliant attacking genius was one of the strongest players in the 1950s. He was a five-time Russian Champion (not to be confused with the USSR Championship). Even though this was a „minor“ competition, just look at the names he finished ahead of in some editions – Lev Polugaevsky (in 1953) and Viktor Korchnoi (1958).

Nezhmetdinov had an overall positive score in ~20 games against World Champions. He was very close to Tal and even served as his second in the 1960 match. On one occasion, in reply to the question: „What was the happiest day of your life?“, Tal answered, „The day I lost to Nezhmetdinov.“

Nezhmetdinov got his IM title in 1954, after a successful performance at the Bucharest International tournament. It is symptomatic to notice how he got the title – FIDE simply decided his performance was worthy of one since other criteria didn’t really exist (source: chessgames).

What is also noteworthy in regard to this tournament is the following: it was only one out of three instances when Nezhmetdinov was allowed to play abroad.

This trademark characteristic of the Soviet era is the reason a number of Soviet masters (Kholmov, Furman, Stein, etc.) are not really well known and appreciated in the west.

It is also one of the reasons why someone like Nez never got beyond the IM title – apart from the fact the GM title was more difficult to obtain, he didn’t get ample opportunities, to begin with.

I think it would be really great if FIDE changed that posthumously.

P.S. Everyone who watches Agadmator’s videos knows he is Antonio’s favorite player. As a matter of fact, Agad has publicly declared he will write a petition to FIDE to award Nezhmetdinov the GM title posthumously if he ever reaches 1 million subscribers.

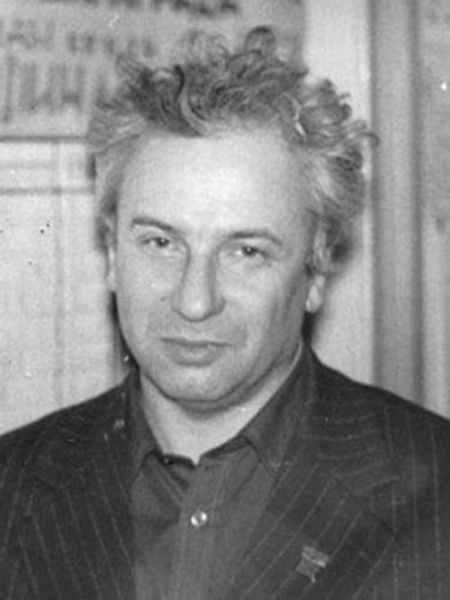

4. Genrikh Mikhailovich Chepukaitis

While we are at Soviet players who aren’t that well known in the West, last year I read the entire bibliography by Genna Sosonko, whose writing is almost exclusively devoted to various players from the Soviet era.

I was particularly fond of the book Chip from St. Petersburg and Other Tales from the Bygone Chess Area, devoted to the lives and games of several masters from that ancient Russian city.

The nickname ‘Chip’ refers to the legendary player, hustler, gambler and character, Genrikh Mikhailovich Chepukaitis.

‘Chip’, who worked as a welder his entire life and was never a chess professional, who never obtained an official international title, was widely regarded as one of the strongest blitz players of his time, if not the strongest.

Already in his first appearance in the Leningrad blitz championship in 1958, Chip, as an unknown 23-year-old, finished second, behind Korchnoi, tied with Korchnoi and Taimanov. He beat all three GMs in individual games.

Later, he would win this tournament six times in total – in 1965, 1967, 1976, 1978, 1982 and – most amazingly – in 2002. In these tournaments, he finished ahead of Korchnoi, Taimanov, Furman and Tal.

All these chess greats acknowledged his strength in blitz. Anatoly Karpov, referring to the shrinking time controls, once remarked:

We might all end up playing blitz, and then Chepukaitis could become world champion.

There is also a story that Petrosian’s wife Rona, notorious for being the “puppeteer” and “pulling the strings” of his husband’s career, once forbid his husband to participate in a blitz tournament where Chip was playing:

[Rona] once prohibited her husband from playing in the Moscow blitz tournament because Chepukaitis was participating: “Tigranchik, you’re the World Champion. Who will praise you if you win? And if you lose? It’s fine if Bronstein, Tal or Kortchnoi beats you, but what if you lose to Chepukaitis? No, you will not play there!”

Even the member of the new generation, Peter Svidler, had nothing but words of praise:

Chepukaitis “in his prime could easily hold his own against World Champions.”

Chip’s strength in classical chess was nearly on the World Championship level, but he was no slouch either.

In his peak, he was rated above 2400, yet he never even got the IM title. Considering he worked as a welder his entire life and probably never played abroad, this rating is indeed remarkable, in my opinion.

I know some people will say that blitz is “random” and not “real chess”, but I honestly think that someone like Chip is worthy of the GM title – probably even more than some people who bear it in this modern time where it can be “easily” “obtained” in closed Bergers and similar tournaments.

I would be very happy if FIDE decided to posthumously award him this title because it would certainly mean a lot to him. In Chip from St. Petersburg, Sosonko describes how, at a certain tournament, the organizers put a sign with Chepukaitis’ name and father’s name initials (GM) on the board where he was playing.

Chip, mistakenly thinking they proclaimed him a Grandmaster, was apparently ecstatic:

You can imagine how sweet it was for him to see on the tournament table for the Senior World Championship in Germany: GM Chepukaitis, when the organizers mistook the initials of Genrikh Mikhailovich for a title

P.S. Apart from Chip from St. Petersburg, my main source for this short overview of Chip’s career was this excellent chesscom article

5. Mark Dvoretsky

Last, but not least, many people know that Mark Dvoretsky is widely regarded as one of the best chess coaches of all time.

What many people fail to appreciate is how strong he was in over-the-board play in his youth. Back in the 1970s, before he devoted himself to coaching, he was a very successful tournament player and definitely one of the strongest Soviet players at a time.

From his Wikipedia page:

He was awarded the International Master title in 1975, and for a time he was widely regarded as the strongest IM in the world. This was due to a number of excellent results: he was Moscow Championship in 1973, finished equal fifth in a strong Soviet Championship in 1974, and won the Wijk aan Zee Masters tournament of 1975 by a clear point and a half. Along with another creditable finish at the USSR Championship of 1975, the results were an indication that he was already of grandmaster strength.

Considering he recently departed from this world, is there a better way of recognizing his outstanding accomplishment and legacy than awarding him an honorary GM title?

I hope you guys enjoyed this list! Feel free to let me know what you think about the article in the comments below.

Also, let me know if there are other players that might be deserving of the honorary posthumous GM title I may have overlooked.

I would be very happy to write part 2 of this article, as well!

I also think that Bannik the Ukranian master deserves a honorary posthumous G. M. title. He played in the USSR Championships 11 times and secured wins against the likes of Tal, Petrosian and Geller. He was also Ukraine Champion twice in the 1940`s .Due to his circumstances he was not allowed to play in events outside of the then Soviet bloc.