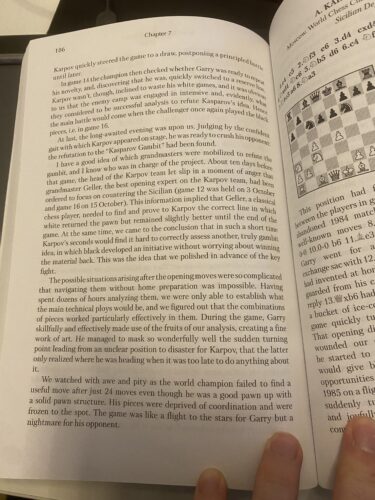

Disclaimer 1: The following article contains several affiliate links to Amazon.com, meaning that if you go to Amazon and buy the recommended product (or some other product in an allotted period of time), the author of these lines will get a commission % from the purchase

Disclaimer 2: Given that the following article turned out to be much longer than I expected. Even though it is still easy to navigate to the specific part of it due to the Table of Content, I have nevertheless decided to post every review as a separate article. The links can be found below:

- Think Like A Super GM by Phillip Hurtado and Michael Adams

- How to Play Equal Positions by Vassilios Kotronias

- 100 Endgame Patterns You Must know by Jesus De La Villa

- The Art of Attacking Chess by Zenon Franco

- The Life and Games of Vassily Smyslov by Andrey Terekhov

- Mating the Castled King by Danny Gormally

- Chessays: Travels Through the World of Chess by Howard Burton

- Endgame Strategy by Mikhail Shereshevsky

- Understanding The Grünfeld by Jonathan Rowson

- Attacking Manual Part 1: Basic Principles by Jacob Aagard

- Sacrifice and Initiative by Ivan Sokolov

- World Chess Championship 1948 by Paul Keres

- Mastering The Sicilian by Danny Kopec

- Your Opponent Is Overrated by James Schuyler

- Chess Queens by Jennifer Shahade

- How To Outprepare Your Opponent by Jeroen Bosch

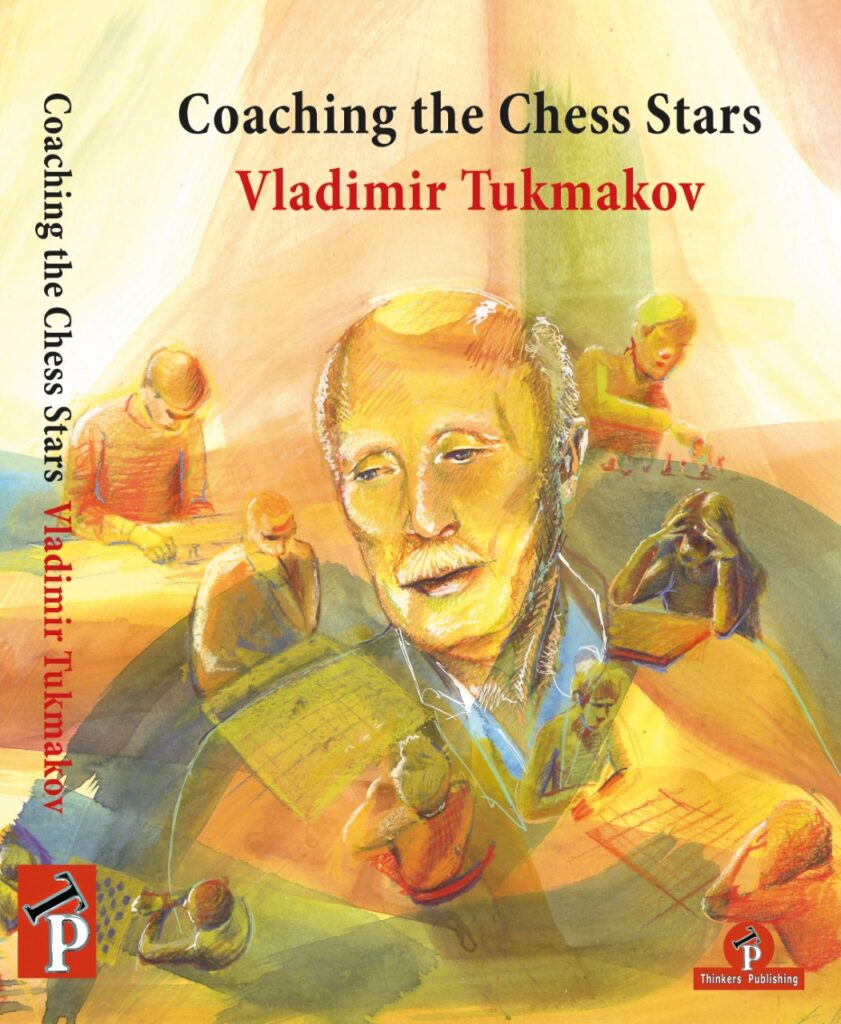

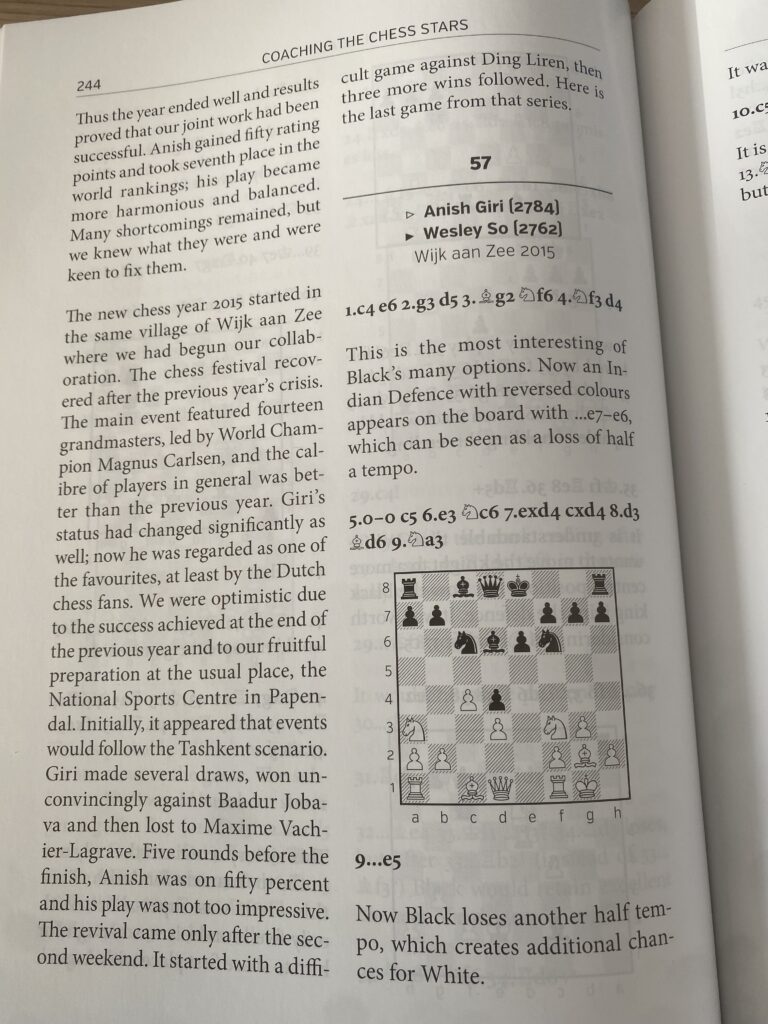

- Coaching The Chess Stars by Vladimir Tukmakov

- Coaching Kasparov by Alexander Nikitin (Parts 1 and 2)

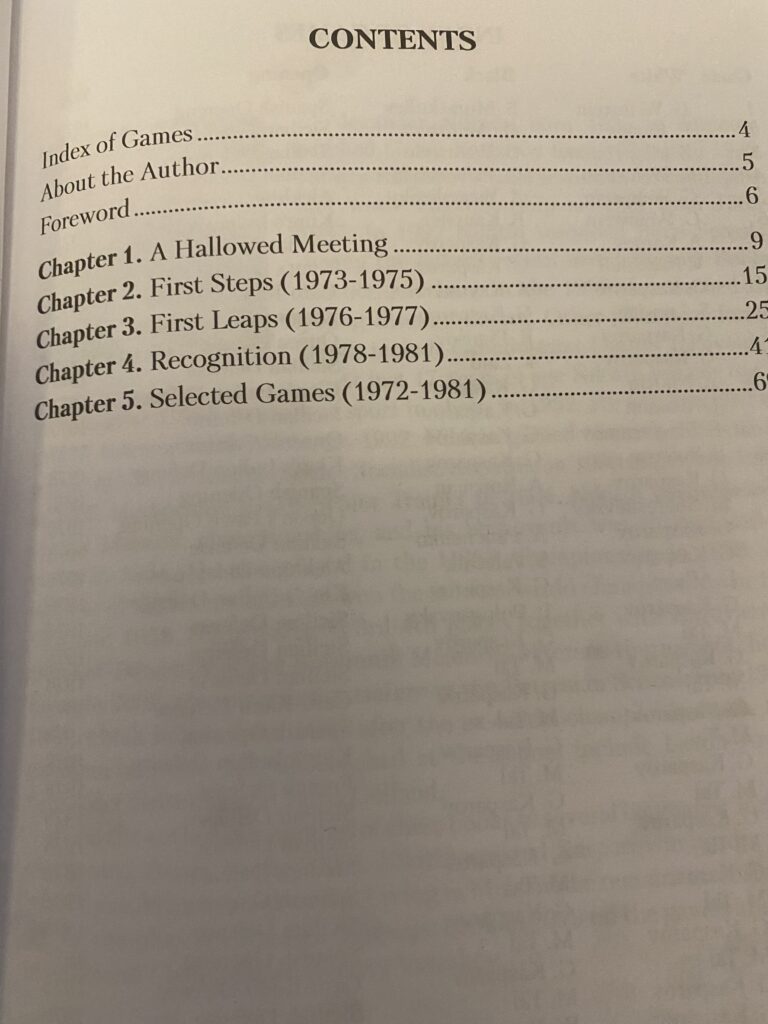

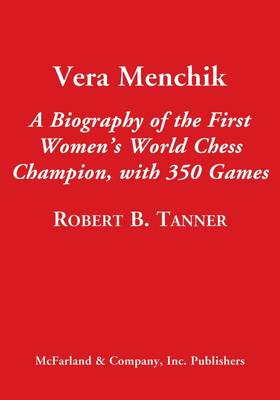

- Vera Menchik: A Biography by Robert Tanner

Table of Contents

INTRODUCTION

2022 was a great year for chess book lovers. I can’t recall when was the last time so many renowned titles were published in the same year. It is crazy to think that books such as Think Like A Super GM, Improve Your Chess Calculation, Evaluate Like a Grandmaster and 100 Endgame Patterns You Must Know were all published in the last 12 months. 1 I have a feeling I have been excited about a new release every few weeks and that I bought more books than ever before.

On the other hand, when I was first assembling this list, I realized that, despite my praise for the 2022 chess book publishing industry, only a few titles on the list are actually from 2022. 2 Also, I have a feeling I actually read way less this year than usual. This is maybe not so apparent in the domain of chess books given that I read a total of 20, which is only 4 books less compared to 2020 when I last made a yearly list similar to this one. But if we are talking about non-chess books, my annual numbers are way lower compared to the peak of 42 books I reached back in 2019.

But that is now beside the point. When we are talking about the chess books one potential reason for the absence of the brand new 2022 titles is my focus on books that I considered important for my own chess development. On the list, you will notice quite a few books devoted to the topic of attack, dynamic play, and initiative, for example – an area of the game in which I felt my game was seriously lacking. Since no new books – to the extent of my knowledge – on this very difficult and niche topic were published in 2022, I had to resort to some of the „classics”.

This focus on the training aspect is also reflected in how I approached reading chess books. This year, I actually made a conscious effort to read books from cover to cover – which involved solving all the puzzles and exercises (provided the book had any). This – together with my general focus on chess training, opening work, and puzzle solving slowed down my reading quite a bit. If I were to stretch it, it is arguably one of the reasons why I didn’t get to all the shiny new titles I purchased throughout the year. 3

To be completely frank, I think this focus on training and improvement was actually a bit counterproductive. There were definitely periods where I felt burnt out on chess – especially since I decided to go full-time on it this year. It is very hard to be „on” all the time and to constantly put pressure on yourself and I am very prone to doing this to myself, given that this is what I wrote in the aforementioned article from 2019:

„Since I have some problems with being constantly productive and doing something “useful”, I have problems with permitting myself to enjoy things in life. I don’t think it is a good sign when it starts manifesting itself in an activity such as reading”

These burnout periods also reduced my motivation to read chess books – especially BECAUSE I often managed to turn reading chess books into another stepping stone on my road to improvement, instead of a leisure and fun activity. This is definitely something I would urge the reader to be aware of. I will certainly try to find a better balance between „useful” and „fun” chess books 4 in the future.

But okay, I have diverted you with my philosophical ramblings long enough. Let’s get back to the main topic of the article and dive deep into the list of Best Chess Books I Read in 2022.

7 BEST CHESS BOOKS I READ IN 2022

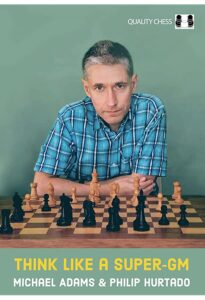

Phillip Hurtado and Michael Adams: Think Like A Super GM

What is the book about?

In 1946, Dutch psychologist Adriaan de Groot – who was also a chess master who played for the Netherlands at two Chess Olympiads – published his landmark thesis titled Het denken van het schaker, which was in 1965 translated under the title of Thought and choice in chess. The thesis summarized the results of a series of experiments de Groot consisting of giving a set of predetermined positions to players of various levels – from amateur to master.

The participants in the experiment were instructed to try and solve the positions and to express their thought process aloud, which was then being recorded for the purposes of the experiment. The goal of the experiment was to shed some light on the thinking process of a chess player – and also what parameters distinguish the thinking process of weaker players compared to the thinking process of stronger players.

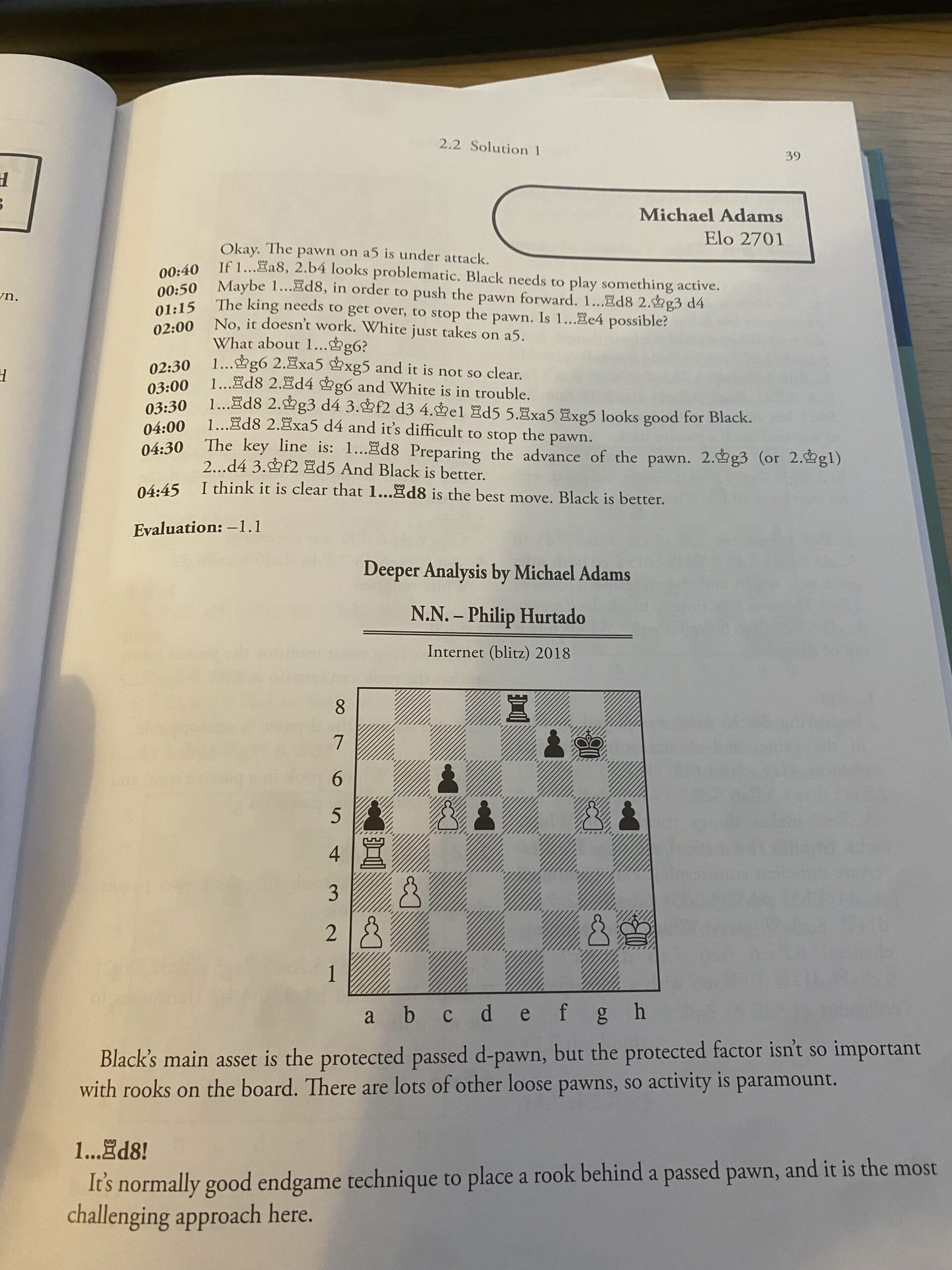

Think Like A Super GM came to life as the result of the collaboration between Phillip Hurtado, a statistician, engineer and physicist, and amateur chess player who came up with the book idea – and GM Michael Adams, the best English player of the last two decades, who was asked by Hurtado to be one of the participants and then got involved in the capacity of the co-author.

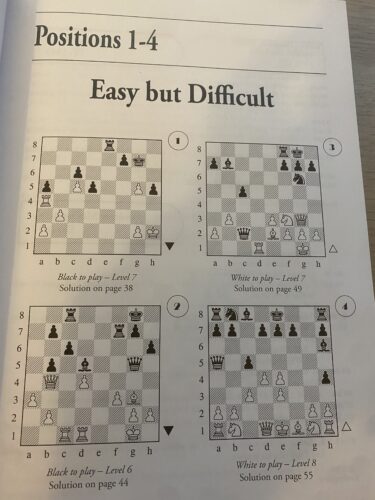

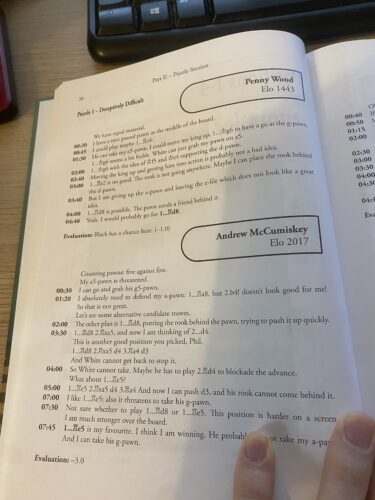

The book is essentially an attempt to replicate de Groot’s experiment in 2022. Hurtado gave a total of 48 puzzles 5 to players of different playing strengths, ranging from unrated to 2700 6 and had them record their thought process as they were solving it. These puzzles with participant notes are then provided in the book, together with solutions and Hurtado’s and Adams’ insights and comments.

The puzzles were mostly taken from Hurtado’s (and sometimes Adams’) games and are varying in theme and difficulty. They also come with a unique scoring system, allowing the reader to score points for each individual puzzle and collect them as they go through the puzzles.

It is, therefore, possible, to test yourself as you go through the book, compare your solutions and thought process with the solutions and the thought process of weaker and stronger players, and learn a lot about the thinking process in chess.

Why do I love this book?

It is hard to understate how great this book really is. The core idea, of course, is unique enough to make the book stand apart on the market. But everything related to the execution of the core idea was done so perfectly that I genuinely consider Think Like a Super GM one of those groundbreaking books that will be talked about for decades to come.

I found it extremely interesting to try and solve puzzles, track my scoring and compare my solutions with the solutions of other players. It was much more engaging and interesting compared to solving your average set of puzzles in an average book – being able to see the thoughts of other players provided me with immediate and very useful feedback and helped me detect the flaws in my own thinking process for those puzzles that I got wrong 7 Hurtado and Adams’ comments – both at the end of each puzzle, as well as the end of the book – very also quite insightful, profound, and interesting. I genuinely think this book does a good job of shedding a light on the thinking process in chess – but also helping you improve your own thinking process along the way.

Another thing I really liked about the book are the puzzles themselves. Given that this is a Quality Chess book, I was a bit worried some of the harder puzzles might be a bit too hardcore. But that was definitely not the case – I found most of the positions – even those with difficulty 9 or 10 – to be more than solvable for someone of my level. Even when I didn’t get the puzzle right 8 I rarely got the feeling of: „Okay, who cares, that solution is way above my head“ – a sentiment that is sometimes encountered in practice, especially if we are talking about Quality Chess books.

The presentation and the structure of the book are also logical and quite neatly done. The only complaint I have 9 is that the analysis given in the solutions to the puzzles sometimes goes to obscure lengths. However, since the book forces you to spend some time thinking about the position before looking for a solution – and since you also have the opportunity to read the thoughts of human solvers before reaching the engine analysis part, I didn’t find it as bothersome or annoying as with some other books.

To conclude, due to its novel concept, fascinating insights, and great puzzle selection, Think Like a Super GM is one of the best chess books I have ever read. If I had to pick only one book from the 2022 list, I would probably pick it and I can only wholeheartedly recommend it to anyone!

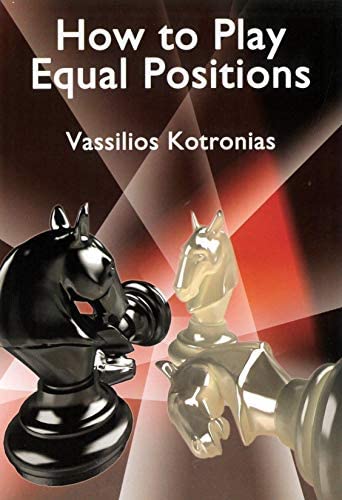

Vassilios Kotronias: How To Play Equal Positions

What is the book about?

As the title suggests, the book How To Play Equal Positions, written by the Greek Grandmaster Vassilios Kotronias and published by the publishing company Chess Stars 10 is devoted to the topic of playing equal positions. Over the course of six chapters and 200 pages, the author discusses several sub-topics related to the main topic, such as:

- How to handle the positions where there is no clear plan available

- When to bail on and when to play on

- Fear of exchanges in equal or close-to-equal positions

- The dangers of overpressing

To put it simply – the book is aimed at helping the reader handle situations where the computer would give the eternal „0.0“ evaluation, yet where there is a lot more chess to be played. 11

Why do I love this book?

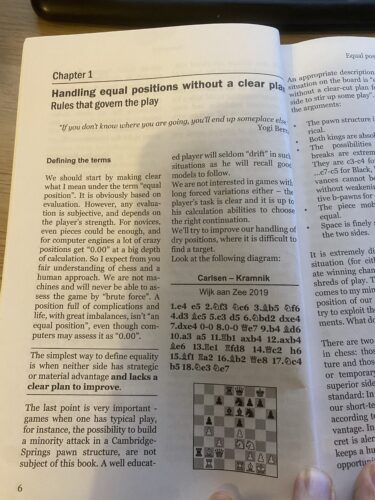

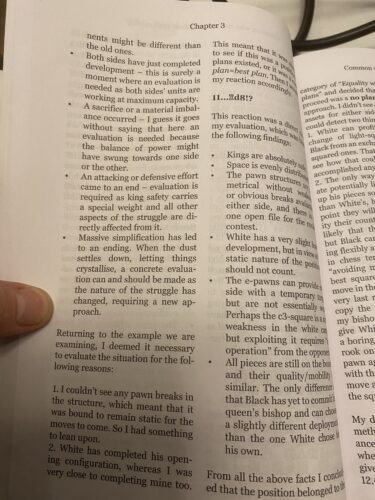

Even though it was published back in 2020, I somehow became aware of the existence of this book somewhere in 2022. Given that earlier that year I crossed 2200 for the first time, the title of the book interested me very much as I realized I am forced to play an equal position with increasing frequency. 12 Thus, even though I wasn’t particularly familiar with Kotronias as an author, I decided to buy the book. And boy, oh, boy – it turned out to be one of the best purchases I have ever made in my entire life.

There is one and only one reason why – text. This book features some of the most thorough, informative, and detailed annotations I have ever seen in the chess book. The author goes to unprecedented lengths to explain the concepts and to shed light on the players’ thinking process during the games. Not only is virtually every single move of every single game followed up with a wall of text, but the author also writes A LOT in between games, summarizing the lessons that were covered in the previous game or introducing new concepts that will be examined in the next game/set of games.

This tendency is apparent from the very beginning of the book. One quick look at pages 6 and 7 of the book will serve as the best evidence:

To be completely honest, I would be full of praise for any chess book with such a heavy focus on textual explanations. But the fact that this one is devoted to such a very complex and convoluted topic makes it extremely good and useful.

It is not only about the quantity of the text, though, but also about the quality. How To Play Equal Positions features some of the most insightful, clear, and compelling explanations of important chess concepts I have ever seen in a chess book. Throughout the book, the author touches on a number of chess-related topics such as playing on a move-by-move basis, pressuring your opponent, posing practical problems, using psychology as a weapon, playing with or without a plan, etc – and explains them in an absolutely masterful way. I remember I was particularly impressed with his thoughts on how and when to evaluate certain positions:

Since many of these concepts are highly useful in all sorts of positions, not just equal positions, I genuinely think this book helps you improve your overall chess skills and thinking process and not just equal positions. And even if it is maybe not the most suitable for absolute beginners and lower-rated players who struggle with tactical issues, I think it is a must-read for any ambitious club player who wants to seriously improve his positional skill, thinking process, and general chess understanding.

Because to my mind, it is one of the most remarkable chess books ever written and I can only wholeheartedly recommend it!

Jesus De La Villa: 100 Endgame Patterns You Must Know

What is the book about?

After the big success of his first book titled 100 Endgames You Must Know, 13 the Spanish Grandmaster and coach Jesus de La Villa made a grand return in 2022 with another book on the topic of endgame, titled 100 Endgame Patterns You Must Know. 14

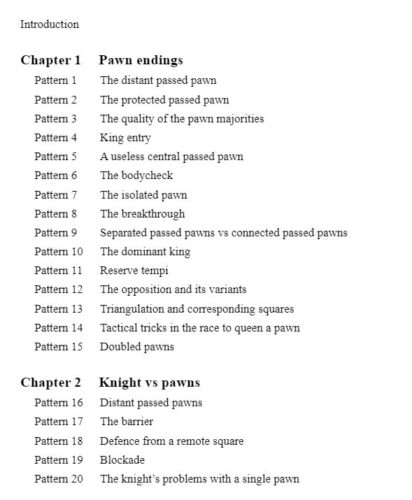

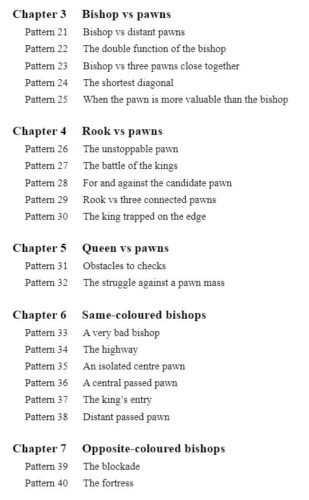

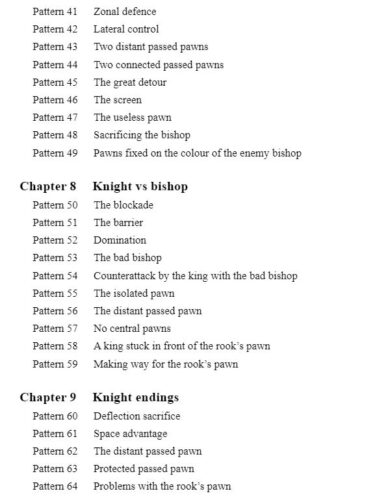

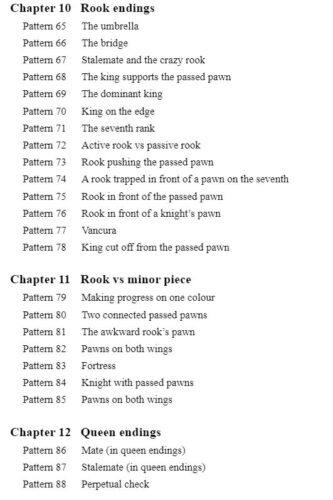

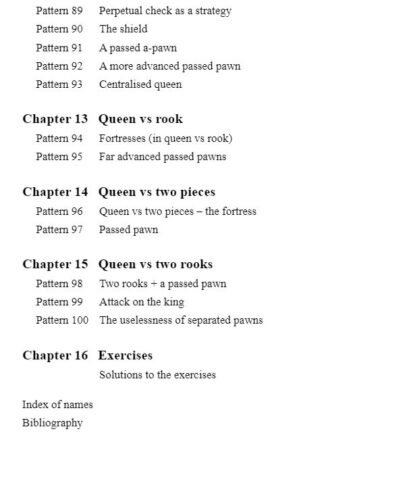

As the title suggests, the focus of the book is endgame patterns. Over the course of 16 chapters, the reader gets acquainted with some of the most important patterns/principles of endgame play, such as blockade, triangulation, distant passed pawns, reserve tempi, lateral defense, zonal defense, barrier, bad bishops, bad knights and many others. The division of the chapters is done on the basis of the piece composition – every chapter is devoted to a different composition (e.g. Rook endings or Knight vs Bishop) and then a set of patterns relevant to that exact piece composition is studied.

100 Endgame Patterns was envisioned as a follow-up/complementary book to 100 Endgames. While the latter primarily focuses on the most important theoretical positions, the 100 Endgame Patterns has a significantly more practical flavor.

The idea is that the two books in combination will provide the reader with a complete toolkit required to play the final phase of the game more successfully.

Why do I love this book?

Even though I am not the biggest fan of the modern tendency to oversimplify and „dumb down“ everything possible in every possible field of human endeavor, I do feel chess endgames are one of the areas where the simplification – especially for educational purposes – is very much necessary. Even though I definitely see the value in books such as The Dvoretsky Manual, I do feel the majority of the chess audience requires something a bit more comprehensible – especially at the beginning of the journey in the magical world of the endgames.

I am, therefore, a big fan of the concept introduced by a book such as 100 Endgames You Must Know. As a matter of fact, back in the day when I first read it, I felt the number of „essential“ positions could have been reduced even further, as I found the majority of these presented in the book mostly irrelevant for the practical play. 15

Thus, when 100 Endgame Patterns You Must Know, I immediately got myself a copy 16 and in 2022, I read it with great joy and interest.

First and foremost – I really liked the way this book was structured and organized. I think dividing the patterns on the basis of the piece composition is very clever and clear from a pedagogical standpoint. It is not a coincidence that another great endgame book I often recommend to people – Understanding Chess Endgames by GM John Nunn – adopts a very similar approach. 17

Second of all, I really liked the selection of examples presented in the book. I felt the choice was much more relevant and useful compared to the 100 Endgames. The majority of examples I have also seen for the very first time. 18 They were also quite varying in difficulty – some of them were very obvious for a player of my level, but some of them I found very challenging and insightful. I felt this variety provides a lot of value to players of different playing levels 19

Last but not least, I really like the way this book was edited and typeset. The abundance of diagrams makes it possible to read even without the board – especially since the majority of the examples/patterns are relatively short. This is usually the case with the majority of New In Chess Books 20, although there are some notable exceptions 21

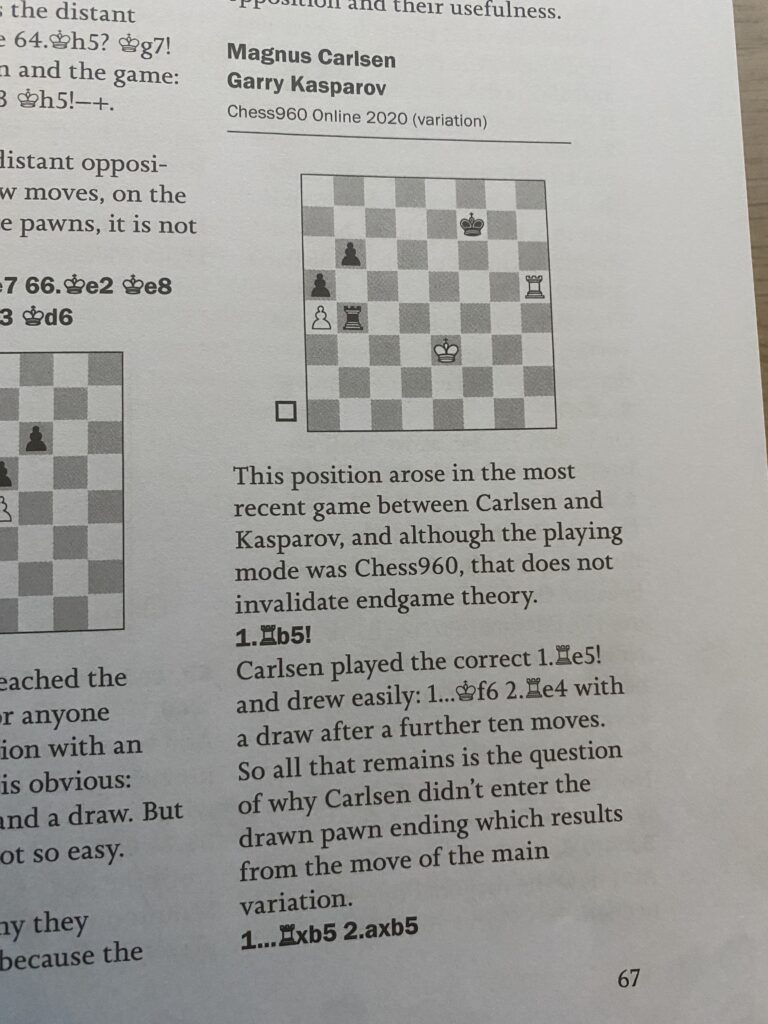

It is true that some of the explanations could be more „verbose“ and thorough and that certain examples feature long variations proving the evaluation of the initial position in the Aagard/Dvoretsky style:

but these instances are few and far between and don’t spoil the general impression of the book.

As for the level – I do think that the book has a lot to offer to players in the range of, say, 1500(1700?)-2300 FIDE. I wouldn’t probably recommend it as your very first endgame book, 22, but I do think it is suitable to be the second or the third.

It is hard to say whether it is better or worse than, say, Understanding Chess Endgames, but I would definitely recommend it before 100 Endgames You Must Know or Shereshevsky’s Endgame Strategy. To say nothing about Dvoretsky’s Endgame Manual.

All in all, a very enjoyable, well-structured, and well-written book and a very welcome addition to the chess literature!

The Art of Attacking Chess: Zenon Franco

What is the book about?

The year 2022 was one of the most successful years for me as a chess player. For the first time in years, I broke the 2200 ELO rating barrier again and even managed to reach my peak rating of 2250. 23

Still, since I hope this is not yet my peak performance, I am always looking for things to improve. And one trend I noticed while analyzing my most recent games – both on my own and with my coach – is my tendency to play very positional, controlled, „old men“ chess.

Therefore, in order to diversify my style and to make it more universal, in 2022 I embarked on the project of reading quite a few books focusing on the more dynamic, attacking element of our beloved game. Among other books, The Art of Attacking Chess by Paraguayan GM Zenon Franco was recommended to me by my coach. And it turned out to be one of the best recommendations for a chess book I have received.

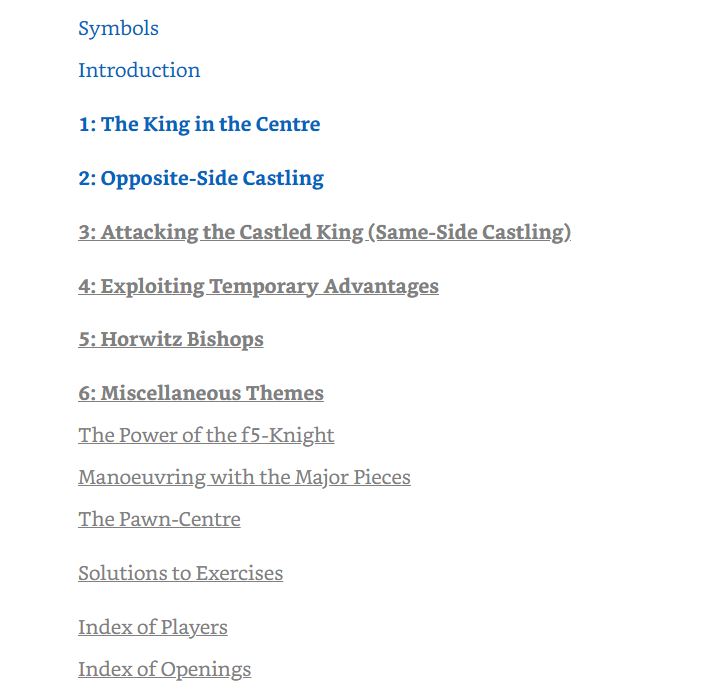

As its title suggests, the topic of the book is attacking chess. Over the course of 6 chapters and 33 annotated model games, the author examines several very important and typical themes related to attacking play, such as:

- The King in the Centre

- Opposite-Side Castling

- Same-Side Castling

Thus, in contrast to some other books on attacking play such as The Art of Attack 24 or, say, Mating The Castled King, which have a heavy focus on concrete patterns and techniques that can be utilized when finishing the attack, The Art of Attacking Chess focuses more on the preparation and build-up leading to these final blows. 25 As the author himself emphasizes in the Introduction:

„ Referring to Alekhine’s extraordinary play, Spielmann once wrote, „ I can comprehend Alekhine combinations well enough, but where he gets his attacking chances from and how he infuses life into the very opening – that is beyond me.“ Achieving the positions where combinations are possible is indeed the most difficult task. In this book we shall not only see games with brilliant conclusions but also examine the different stages in the creation of these finishes.“

Why do I love this book?

Good question! In contrast to some other books on this list that delighted me with a particular aspect, say a novel book idea, freshness in the writing style, or absurd amounts of text, 26 The Art of Attack In Chess doesn’t have anything that immediately stands out about it. The reason why I love it is much more mundane and simple – it is simply a very good chess book that gets all 27 fundamentals just about right.

Let’s start with the structure and the organization of the material. The way the book is divided is very reasonable and sensible – and the topics that are covered seem very important and very relevant for practical play. 28 Every chess player is bound to find themselves in a position where the opponent has a king in the center or where the kings are castled on opposite sides. I also liked how the author provided the reader with a set of exercises related to the given topic after every chapter.

And even though some of these topics are covered in other books, I can’t recall when was the last time when it was done in such an elegant and logical fashion.

Another thing I really liked about the book are the games themselves. They are, first and foremost, very exciting and interesting, while at the same time retaining that instructive component that is important for a chess book. The author does a good job of illustrating several important sub-topics within the main topic and often references earlier games when analyzing the current one.

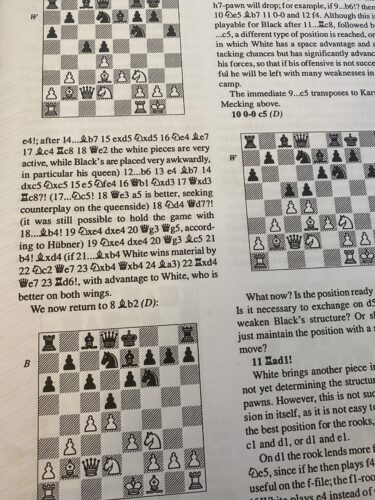

One thing I also like about the book is its objectivity. The author doesn’t tell us to attack at all costs, but tries to teach us under which circumstances is the attack well-timed, and under which it is premature. There are quite a few examples demonstrating the latter. I particularly enjoyed Game 21 from the chapter on Exploiting Temporary Advantages:

The amount and the style of textual explanations is also much higher than in your average chess book. 29 This is especially apparent in the introduction to every game, where the author foreshadows the important theme/several themes that the game illustrates – and also in the conclusion to every game where the author summarizes the lessons we can extract from it. Again – nothing extraordinary or out-of-this-world. But very solid and more than sufficient.

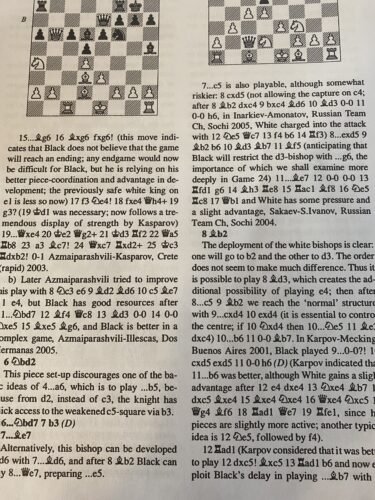

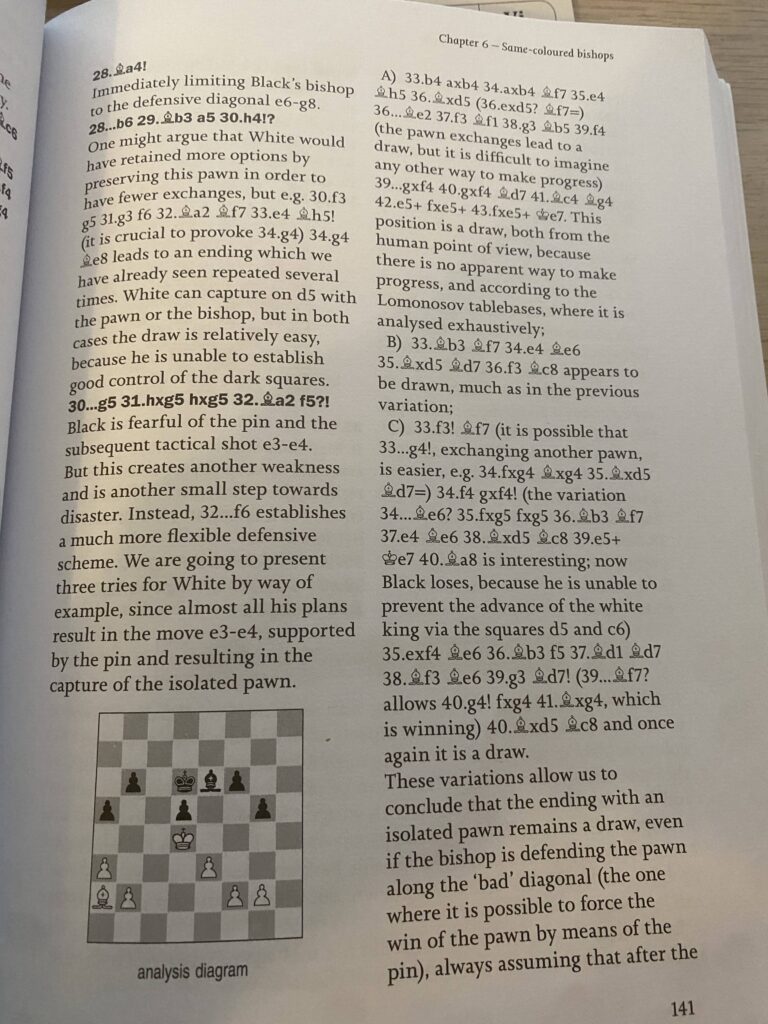

The analysis of the games, on the other hand, is the only issue I have with this book, due to its protracted nature. There are quite a few places in the book where the author embarks on lengthy explorations that take 10+ moves. And even though one could make an argument it is necessary for a book dealing with such a complex topic chess, more often than not I felt it was overdone. Especially since there are quite a few places where these analytical escapades are done very early in the opening – for example on move 8 of the game 23 on pages 131 and 132 of the book:

It is true that The Art of Attacking Chess contains more diagrams and better-placed diagrams than your average chess book. But due to the prolonged nature of the analysis, it is still impossible to fully follow the book without the use of the board – or to follow the subvariations in your head when going through the main line on the board.

Alas, in regard to this, I have a very clear bias – if I like the book in general, I will not have that many problems with the fact I need to use the board to read it. But if I don’t like it, then all the other aspects of the book will be more bothersome, as well.

Fortunately, The Art of Attacking Chess is the case of the former. I don’t think that these editing limitations are sufficient to negate the fantastic and instructive content that the book contains and I can only wholeheartedly recommend it!

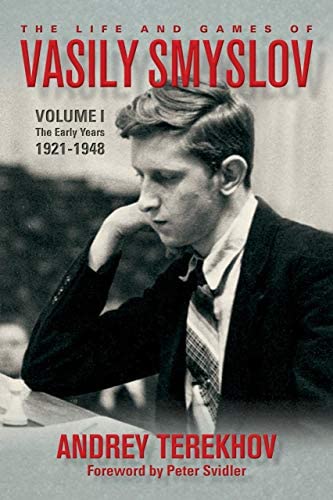

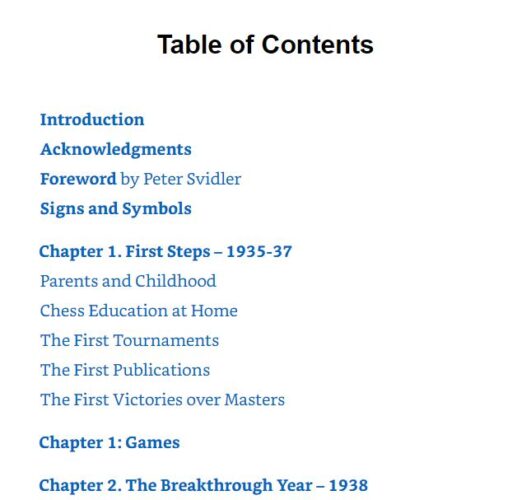

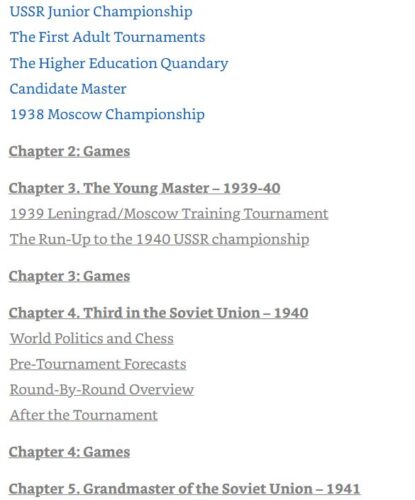

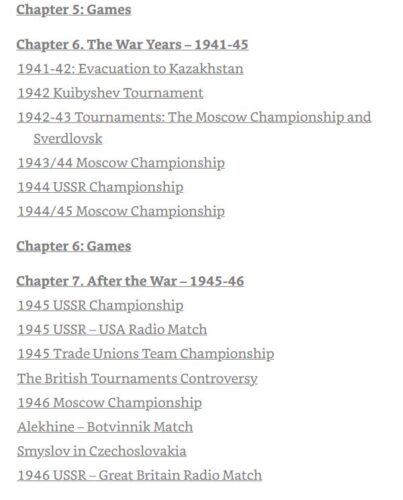

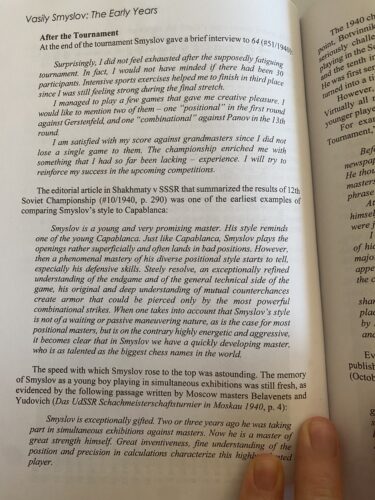

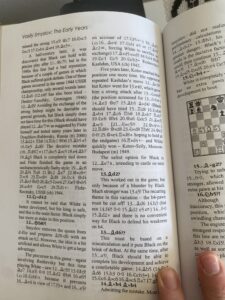

Andrey Terekhov: The Life And Games Of Vasily Smyslov, Volume I, The Early Years, 1921-1948

As the title suggests, the book is devoted to the earlier, arguably lesser-known, part of Vasily Smyslov’s career, covering the 1921-1948 period over the course of 10 separate chapters. Every chapter is split into two parts, the first one covering the events and telling the story and the second one featuring Smyslov’s games from the given period. The book concludes with a special chapter about Nadezda Andreevna (Smyslov’s wife) and even features two specialized chapters – one about Smyslov’s System in the Grünfeld defense, and one about Smyslov’s Endgames (specially prepared by a renowned endgame specialist Karsten Müller).

Why do I love this book?

I first got acquainted with the name of the Russian Fide Master, ICCF International Master, and owner of the Ph.D. in Computer Science, Andrey Terekhov, on Twitter, when someone shared an article he wrote for chess 24 about the early years of Vasily Smyslov.

I was thoroughly impressed by all aspects of the article, but especially with the amount of research that was poured into the article, evident from the abundance of historical resources referenced throughout the article. When I realized this article is only an excerpt and that Andrey is writing a full book devoted to Smyslov’s Life and Games, I was immediately excited. When the first part, titled The Life and Games Of Vasily Smyslov, Volume I, The Early Years, 1921-1948 came out, it was, thus, a no-brainer for me to purchase it. 30

In my mind, this book sets a gold standard when it comes to chess historical/biographical books. The amount of research and historical references is almost unprecedented. Almost on every other page, there are quotes taken from old magazines 31, newspapers, and other books and publications. Just like in his articles, Andrey Terekhov doesn’t make any claim without substantiation and one can only imagine how much time and effort was put into the research and compilation of all these historical sources.

On the other hand, despite the abundance of historical sources, the book is not dry or boring to read by any means. Just like in his articles, Andrey manages to weave the historic data with his masterful writing and storytelling to create a very compelling, interesting, and not-too-difficult-to-read narrative.

To be fair, the fact that the entire 1921-1948 era is extremely interesting not only from the chess perspective but from a general historical perspective, probably didn’t hurt. Maybe it is just me, but I can never read enough stories from these old Soviet times – especially if they are connected to chess. I find learning that Smyslov was a big celebrity who had genuine „groupies“ from whom he received regular letters, realizing that he was a part of the aviation squad during World War II, or just reading about chess life in the Soviet era in 1940-1945 endlessly fascinating.

As for the chess aspect of the book, it is also of very high quality. The games are carefully selected and thoroughly annotated, with a lot of annotations and meaningful textual explanations. True, the author does heavily rely on the engine 32 and there are certain instances where the engine analysis is prevalent and may be overly prolonged, but these instances are few and far between.

Now, the aspect I didn’t like as much as the very decision to split the chapters into two parts. The problem is that in the first part of the chapter, the author often references key games in the context of a specific tournament – but then they are provided in the second part of the chapter. This means that the reader often has to scroll back and forth between the two parts of the same chapter to connect the game to the specific moment in the specific tournament.

Another aspect of the book that I didn’t find as enjoyable is related to the amount and layout of diagrams provided with each game. Even though the analysis is mostly not that hardcore and prolonged, it is still not possible to read the book entirely without the board. There are even pages where not a single diagram is provided:

Another minor trifle I have with this book 33 are not-so-ideal line breaks, as there are quite a few instances where a sentence/variation starts on one page and ends on another page, making the reading process even more difficult.

But all these issues are not major enough to spoil the overall impression of the book and to overshadow the tremendous effort, research thought, and love that went into the writing of this book.

There is a reason why it got the FIDE Book of the Year 2021 award and why the foreword was written by none other but the legendary Russian Grandmaster Peter Svidler.

I can only wholeheartedly recommend it – especially to those with a marked interest in chess history and Soviet times.

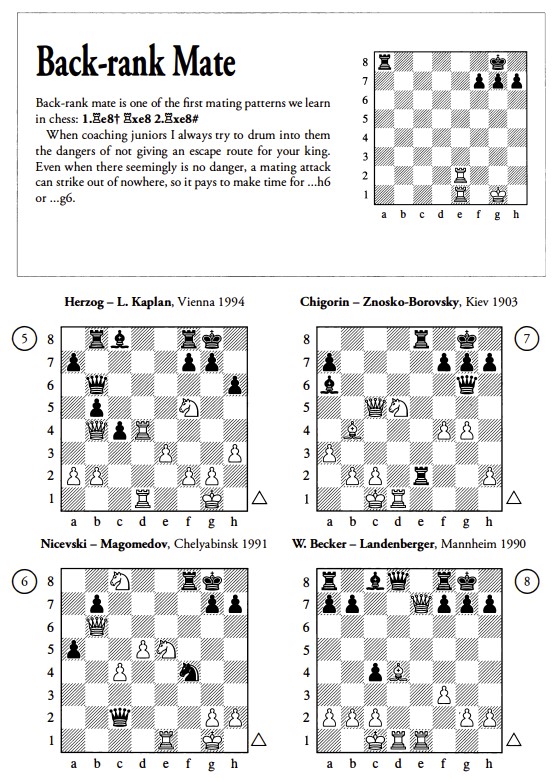

Danny Gormally: Mating The Castled King

What is the book about?

As I mentioned earlier in my review of The Art of Attacking Chess 34, in 2022 I spent quite some time reading books on the topic of attacking and dynamics. Among other titles, another one I enjoyed this year is another Quality Chess book written by the British Grandmaster Danny Gormally and titled Mating The Castled King. Since I was already familiar with Danny’s work through my work on Chessable, 35 I was aware of his style and his gift for writing. Thus, when my coach also suggested I check this book, I gladly dived deep into it.

As its title suggests, the book heavily focuses on the topic of giving mate to the opponent’s king. After the first, introductory chapter, we dive straight into the largest chapter of the book, consisting of 160 examples where the goal is to deliver the checkmate to the enemy king.

The examples are divided into 20 subchapters, on the basis of different motifs/piece configurations and are presented in the exercise–solution form. At the beginning of each subchapter, the position diagrams are provided as puzzles – and only later in the chapter is each separate position discussed and analyzed. Even though the motifs (say, such as Greek Gift) are relatively well-known, the exercises are not always that trivial and I very much liked such a presentation, as it forced me to try and solve them before searching for the solution. 36

Now, if this was all there was to this book, I would have probably still regarded it quite highly, but I probably wouldn’t have included it on the list of the best books I read in 2022. However, Mating The Castled King is not only a checkmating but also very much an attacking manual. Because chapters 3-6, or more than half of the book, are devoted to attacking play. More precisely, to classical attacking techniques: attacking with the pieces and attacking with the pawns.

Apart from teaching us WHEN an attack with the pieces or the pawns should work, the author does his best to also explain WHAT the typical attacking methods are. The second half of the book has a very heavy emphasis on pattern recognition as the author writes in great detail about typical piece sacrifices, typical pawn breaks, methods of opening the enemy king in situations with opposite side castling, and much more.

Last but not least, the final chapter provides the reader with additional 12 exercises, prompting them to test the knowledge and check to which extent they have internalized the lessons from the earlier parts of the book.

Why do I love this book?

There are several reasons I am very fond of this book. First of all, I think Gormally is a very talented writer with an engaging writing style. Not only are his explanations elaborate and very thorough, but they are also accompanied by a healthy dose of self-deprecation and a dent of typical British irony, which appeals greatly to yours truly and makes the prose very enjoyable to read.

Secondly, I really like the book’s logical and crystal-clear structure and content. I think the author has found a very fundamental and instructive way of presenting material related to attacking chess. I think it is educational to have a section devoted to attacking patterns and then a section devoted to some attacking techniques. I think such a way of approaching the topic of attacking chess is quite didactic and very suitable for someone newer to the game.

That is not to say that the book is aimed at beginners or that it doesn’t have anything to offer to stronger players. Even in the section devoted to mating patterns, the puzzles provided are of varying difficulty – some of them I got instantly, while some of them presented a much greater challenge. None of them were as hardcore, as say, the puzzles in Aagard books, but they can definitely be regarded as too easy.

I would, therefore, not recommend the book to total beginners. 37 I would recommend it to someone who is not a complete beginner and who has potentially acquired some basic knowledge of mating patterns via a book like The Art of The Checkmate or The Checkmate Patterns Manual 38

Thus, if you are someone who fits this description, or someone who doesn’t care that much if the book is „NoT aBsOlUtElY sUiTaBlE fOr ThEiR lEvEl AnD oPtImAl FoR iMpRoVeMeNt“ and are just looking for a well-written, high-quality book, I can wholeheartedly recommend this one.

P.S. This book is also available on Chessable 39

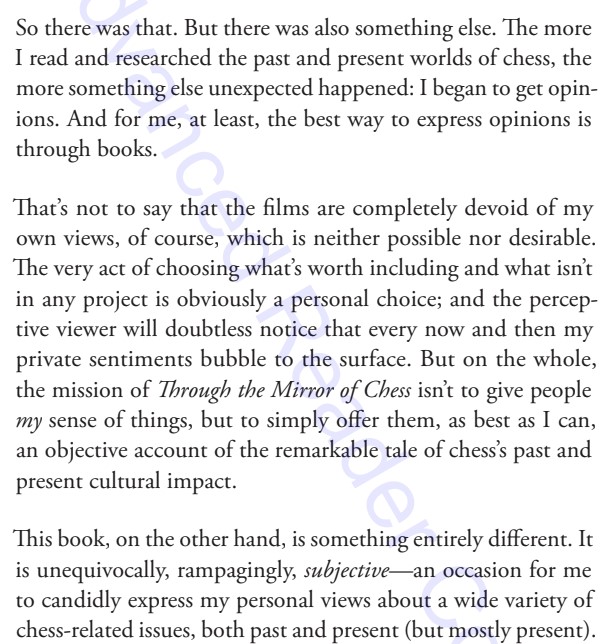

Howard Burton: Chessays -Travels Through the World Of Chess

Howard Burton is an independent filmmaker, author, and founder of The Ideas Roadshow, which describes itself as „an award-winning multimedia initiative dedicated to harnessing the benefits of modern technology to explore ideas across the arts and sciences through thoughtful and seriously-entertaining documentary films, books and podcasts.“ In simpler terms – a multimedia initiative that publishes books and movies produced and authored by Howard on a variety of topics from different fields, based on a series of conversations Howard conducts with experts from these same fields.

And his own research and observations.

In March 2020, Howard started working on a documentary film on the topic of chess, titled Through The Mirror Of Chess: A Cultural Exploration. By his own admission, he initially expected it wouldn’t be such a lengthy and encompassing project, but then the pandemic and the chess boom happened, and he got more and more immersed and ended up accompanying the movie with a book about the chess world titled Chessays: Travels Through the World Of Chess.

As the title suggests, the book consists of a series of essays – 8 to be exact – giving Howard’s thoughts on a variety of topics from the chess world, as follows:

- Chess history and chess historians

- Is chess a waste of time? What activities are not regarded as a waste of time?

- The cultural status of chess. Should it be regarded as a sport? If yes, under what circumstances?

- FIDE

- The eternal question of gender, sexism, male bias, female-only tournaments, and competitions

- Are chess skills transferable to other domains

- Chess as a vehicle for societal changes?

- Chess in relation to technology and artificial intelligence

In contrast to the majority of the chess books on this list, 40 this book doesn’t contain any chess moves and diagrams. It is a purely subjective, personal 41 account of the chess world from the perspective of an outsider.

Why do I love this book?

In the second half of 2022, I got contacted by Howard’s partner Irena, who mentioned he is working on a four-part documentary series about the world of chess and also writing a book. She asked me whether I would be interested in reading and reviewing the book, as well as the movie. 42 Despite my initial skepticism caused by me being a staunch chess elitist, 43 I decided to keep an open mind and read the book at the end of 2022. 44

It turned out to be one of the best decisions I have ever done since Chessays turned out to be one of the most profound, interesting, entertaining, humorous, and thought-provoking books I have ever read. Not only if we are talking about chess books, but about books in general.

It is hard to even begin to explain how and why this book is so good. I absolutely love every aspect of it, but for the sake of this article, I have singled out five characteristics that delighted me.

- Opinionation

If you have ever read any of my other articles 45 or my Twitter, you might have noticed that I am a very opinionated person and that I love shoving them wherever and whenever possible.

Part of being opinionated is very dismissive of other people’s opinions, at least when you don’t agree with them or consider them dumb. In the aftermath of the Great Chess Boom caused by the pandemic/The Queen’s Gambit, we have seen all sorts of newcomers 46 express all sorts of stupid opinions about many things related to chess. 47 Thus, when I realized that the main purpose of this book was for the author to share his opinions with a broad public (which is announced in the very introduction of the book), I was immediately intrigued and eager to find out more.

To be fair, my eagerness was very much based on my willingness to read the author’s arguments and then laugh them off. Since I didn’t do my research properly, I expected to read a superficial, half-informed account of the chess world based on a few newspaper headlines, Youtube videos, and clips from GMHikaru’s stream.

Oh boy, was I wrong. The book not only turned out to be superficial and half-informed – it turned out to be one of the most informed, meticulous, and well-researched I have ever read.

This leads me to the next point.

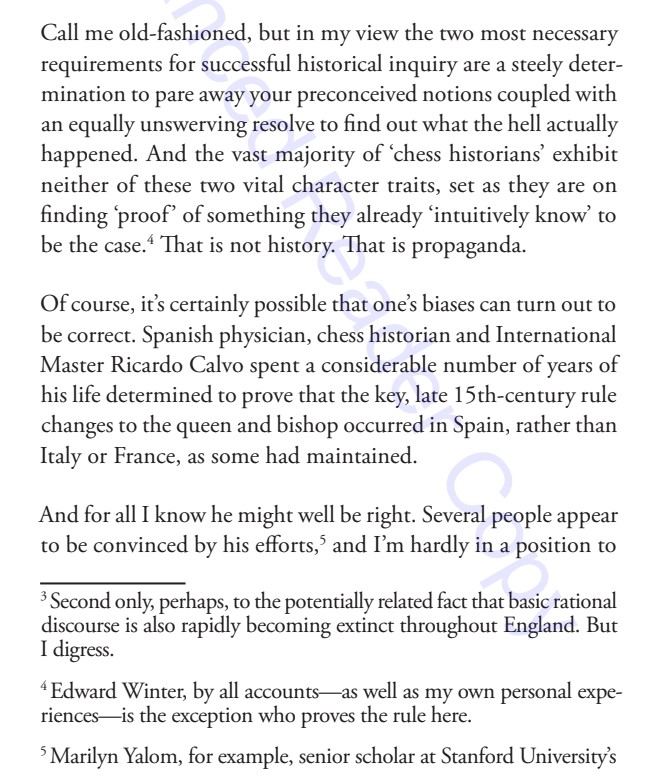

- Deep insights and knowledge about the chess world

One thing I didn’t immediately realize before I started reading the book is that Howard Burton is a very intelligent, meticulous, and thorough individual – which is not surprising given that, apart from his writing and filmmaking credentials, he also holds a Ph.D. in physics.

Pretty much from the very first chapter of the book devoted to chess history and chess historians, it was quite apparent that Howard has done his research and immersed himself very deeply in the chess world. Not only does he display quite big erudition related to the origins of the chess game and early publications – but already as early as page 10 he already mentions the name of the renowned chess historian Edward Winter – the founder of the website chesshistory.com – and pretty correctly recognizes his trustworthiness and credibility. 48

The fact that the author has done the research and is well-versed in the chess world keeps being apparent throughout the book. References are made to famous streamers, Youtubers, FIDE officials, players, historical figures, initiative leaders, and many others. Whether we are talking about Jerry from the Chessexplained Youtube channel, Arkadij Dvorkovitch or Pontus Carlsson, you can be sure that Howard has heard about them – and in many cases interacted with them.

Thus, irrespective of whether you agree or disagree with his opinions, 49 claiming that they are baseless and uninformed would definitely be unjust!

- No filter in writing

Now, considering Howard’s academic background 50 , you might expect the writing to be…well… very academic, dry and correct.

Not only is that not the case, but the writing is completely on the opposite side of the spectrum. One thing I really like about Chessays is the fact that Howard has absolutely no filter. If there is an opinion/point to be made, Howard will make it very directly and succinctly, without beating behind the bush or caring whether someone might get offended in the process.

One of the favorite groups Howard likes to insult is chess players themselves. As early as page six, we get the taste of what is to come:

Slightly later, on page 28, we get another round, but this time we share the burden with the respected citizens of the United States of America:

I think by this point, it has become clear that, if Howard thinks someone deserves to be called an „idiot“, you can be sure he will let you know, irrespective of what their name or status within the chess world is. And while calling Nigel Short an „idiot“ might not be very revolutionary:

expressing very harsh, yet well-founded and reasonable criticism of Garry Kasparov is not something you have the opportunity to read every day:

Of course, some people might be immediately put off by this „Talebian“ language, 51 but I honestly find this candid and open writing style endlessly entertaining and refreshing in the era where everyone is treading so carefully and trying oh-so-hard to be politically correct at all times.

Especially since I felt that Howard is very masterfully balancing the thin edge between being funny and being purely offensive and is never really crossing it. I personally found not only these „offensive“ remarks but the book as a whole absolutely hilarious.

This brings me to the next point.

- Humour/writing style

As you might have figured from the screenshots I shared above and the general tone of the review so far – I think Chessays are absolutely hilarious. Howard strikes me as a person who doesn’t take anything – including himself – too seriously and I find his sharp remarks insightful and witty at the same time. I remember I was endlessly entertained by his comment in regard to chess historians which can be found on page 13 of the book:

One trait of Howard’s writing that reinforces the feeling of humour and jovial tone is the use of the footnotes throughout the book. As you might have figured out from reading this article, I am very fond of trying to make pitiful humoristic attempts in footnotes – and Chessays use this technique all over the place. As can be seen from the screenshots above, the majority of humorous and snarky remarks are actually hidden within the footnotes. And at a certain point in the book, the author intentionally mocks himself for that tendency:

Of course, if it were only about insults and humour, this book probably wouldn’t be nearly as good as it is. However, as it usually happens – people with the innate ability to be extremely funny are often the people who have the innate ability to be extremely intelligent and profound.

This leads me to the final part of this review.

- Profound and original ideas, thoughts, and observations

From what I have written so far, you might get the impression that this book is a semi-serious, half-baked attempt to write a humoristic piece about the chess world and insult as many chess players as possible in the process and that the author doesn’t really care for the chess world as a whole.

Nothing of the sort.

Through Chessays, the author elaborates on what he thinks are some of the burning problems of the chess world that prevents its further growth and limit its potential – and tries to propose concrete solutions for solving these problems.

I can’t recall when was the last time I encountered so many profound and original ideas and potential solutions regarding some very concrete issues we are facing as a chess world. The most interesting proposal was for the chess players to find a separate organization under the auspices of FIDE:

and for the female players to do the same, very much how it is done in tennis with the existence of the ATP and WTA:

This model proposes FIDE to be more of a regulatory body, rather than an organizational body with the central power. Definitely, a profound concept that is worth exploring further.

And this is just the tip of the iceberg. Throughout the book, Howard comes up with very profound ideas and observations about a myriad of other issues, but this article would very quickly get way too long if we started to explore all of them very deeply. 52

I think it is much easier for you to read the book. I can only wholeheartedly recommend it and you will definitely not regret it!

13 OTHER CHESS BOOK REVIEWS

Mikhail Shereshevsky: Endgame Strategy

Even though I have obviously heard about this famous endgame book and even though former collaborator on Chessentials Bruno Pavčević once reviewed it for this blog, it wasn’t until 2022 that I finally decided to actually check it out. Purely by coincidence, I did it at the beginning of the year, before the new and revised edition was published by New In Chess later in the year (and also on Chessable with the video presentation by GM Sam Shankland).

Endgame Strategy is a famous book devoted, well, to the strategy in the endgame. 53 In contrast to some other endgame books which cover different types of endgames in terms of pieces (Rook Endgames, Minor Piece Endgames, Queen Endgames, etc.), Endgame Strategy takes a slightly different route and approaches the endgame from the standpoint of endgame principles.

Over the course of 13 chapters, the author covers typical endgame principles such as the Centralization of the King, „Do Not Hurry” or The Principle Of Two Weaknesses. 54 Every chapter is supplemented with a series of examples (usually somewhere between 5-10, depending on the chapter) devoted to the topic at hand. The majority of examples are game fragments, although occasionally, the authors provide the readers with full games.

For the most part, the examples are really well-selected and highly instructive. The book is full of games by old champions such as Capablanca and Lasker and Soviet masters of the 1950s and 1960s, often featuring positions that might have as well arisen in one of our own games.There is definitely a tremendous value in setting these positions up, thinking about them, and playing through them while following the explanations.

With that being said, there were a few instances where the selection of examples caused me to raise an eyebrow. For example, take a look at the opening example of the 5th chapter of the book, devoted to the „Don’t Hurry” principle. I felt this is a very strange choice for the opening example of a very counterintuitive and difficult theme – not only because I think it is not the best demonstration of the „Don’t Hurry” principle – but also because the author’s analysis of this example is significantly flawed.

This brings me to the main problem with this book – the weakness of the game analysis. It is true that the mistakes in the analysis of the book originally published in 1981 are to be expected, but in my mind, in the Endgame Strategy, this reaches epic proportions. There are so many positions like the one given in the diagram above where the author totally misses the evaluation of the position.

I tried ignoring this aspect of the book as much as possible and simply play through the examples to get the feeling for these endgame positions. But in situations like this when the entire evaluation of the position was off the mark and when I had a zillion of questions even before I entered the position in Chessbase and turned on the silicon friend, I personally found them very bothersome.

Especially since I felt that the author of the book could have done a much better job when it comes to annotating the examples and stopping to explain some key points. Sure, at the beginning 55 of each example, a lengthy elaboration of the position on the board and how to apply the principle of interest is present, but once the moves start floating, I have found the commentary rather sparse. Very often in the book, there are long series of moves left without any text whatsoever. Maybe the most egregious example is featured on page 46 of the book:

I felt it would have been much more beneficial if the authors cut some examples earlier and used that space to add some more positions – or additional diagrams. Because the distribution and the number of diagrams in the book make it very difficult to read it without the use of the board.

In combination with the previously mentioned issues, this resulted in me basically entering every single example in Chessbase and clicking through it while simultaneously going through the text, which was – quite frankly – a tedious and frustrating experience, which kinda diminishes the point of reading a chess book, to begin with.

Thus, after going through the book I can’t avoid the feeling that it is one of those classic books that is nowadays somewhat outdated and quite overhyped. You might make an argument that 2200+ players are maybe not the target audience, but while I did find it quite superficial for my needs – I also feel it is quite complex and difficult for the players on the relatively lower end of the spectrum.

I honestly don’t know how many of these issues were corrected in the revised edition. But if I were to recommend a book on the topic of endgame strategy, I would probably recommend something like Understanding Chess Endgame by GM John Nunn 56 to lower-rated players or the renowned Mastering Endgame Strategy by GM Johan Hellsten to higher-rated players. I also think books such as 100 Endgames You Must Know and 100 Endgame Patterns You Must Know offer you a greater value for the buck while being immensely less frustrating and confusing to read. 57

Jonathan Rowson: Understanding the Grunfeld

As some of you might know, somewhere in March 2021, I decided it is finally time to ditch my beloved Modern and start playing some proper openings. When Peter Svidler released his Chessable course in April 2021, I took it as a sign from above and decided to pick the Grünfeld as my main weapon against 1.d4.

However, despite spending a large part of 2021 clicking through the course and even scoring some nice victories with Svidler’s lines in January 2022 58 I realized I still don’t fully feel the resulting Grünfeld positions and that I mix up my move orders way too often. 59 Thus, at the suggestion of my coach, I decided to pick up a Grünfeld resource that would be more oriented toward understanding. Thus, the book titled Understanding the Grünfeld, written by a renowned author and philosopher GM Jonathan Rowson (whose book Moves That Matter I rated very highly back in 2019) seemed like a very logical choice

Understanding the Grünfeld, is essentially, a Grünfeld repertoire book. Out of the total 14 chapters, approximately 11.5 have a heavy theoretical flavour. If we disregard early deviations, Londons, and Tromps, this book covers it all – from rare 3rd moves to main variations of the Grünfeld.

Alas, as expected from an opening book written in 1999 – a lot of the material presented in it is quite outdated. Many 60 lines proposed by the author are not the best from the standpoint of the modern theory – while some of them are just outright unplayable. From a purely theoretical perspective, the book simply doesn’t stand the test of time. 61

The value of this book is primarily contained in the 2.5 non-theoretical chapters – as well as parts of theoretical chapters – where the author talks about key Grünfeld ideas, motifs, and concepts such as dealing with the passed d-pawn or handling the typical Grünfeld endgames. Whereas concrete lines are constantly changing, the fundamental ideas behind any opening are very much permanent – especially if we are talking about the lower-rating levels. In these chapters/chapter fragments, the author really does try his best to help you understand the Grünfeld, as opposed to purely trying to memorize it.

Since I am also a big fan of Rowson’s introspective, evocative and elaborate writing style, it is not surprising that this book did appeal to me despite its theoretical deficiencies. Since it has a huge number of Model Games, I think there is a lot of value in playing through them and in treating it as a non-opening book.

Although I will admit it is probably not the most efficient way to go about learning the opening as complex and theoretical as Grünfeld.

Jacob Aagard: Attacking Manual 1: Basic Principles

If anyone out there is not familiar with the name of GM Jacob Aagaard, he is a Scottish Grandmaster of Danish origin with a peak FIDE rating of 2542. However, rather than for his playing achievements 62 he is much better known nowadays due to his work as a chess trainer, chess writer, book editor and publisher.

He is one of the main coaches of the American superstar and former US Champion GM Sam Shankland 63, the founder of the platform Killer Chess Training and also the founder of the Quality Chess book publisher (who published the aforementioned book Think Like A Super GM, among a myriad of other high-quality titles).

Aagaard is also a very prolific chess writer, who has written more than 20 books since 1998. However, it is not only about quantity – his books are well-known and highly regarded due to their very high quality. Almost any stronger chess player will be familiar with at least one of Aagard’s titles and it is not really surprising a number of his publications have received multiple awards.

Aagaard has written books on different topics. But since I was focusing on improving my attacking play in 2022, I decided to start with the first part of the two-series book devoted to this very topic, titled Attacking Manual 1: Basic Principles.

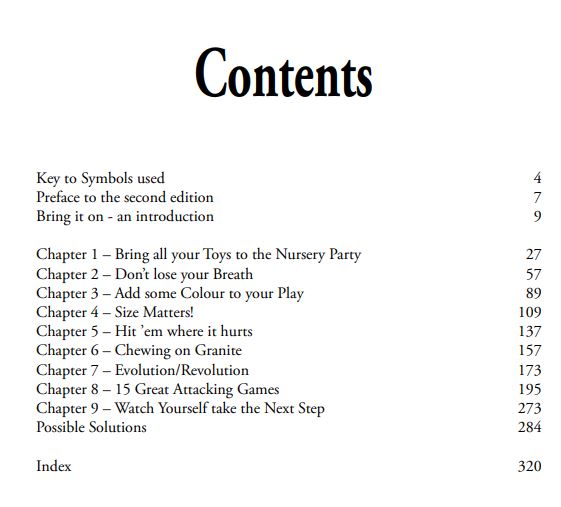

As the title suggests, the book focuses on what Aagaard considers to be the basic principles of attacking play, as follows:

- Chapter 1: Bring All Your Toys to the Nursery Party – a chapter about including every single piece into the attack

- Chapter 2: Don’t Lose Your Breath – a chapter about momentum and maintaining it throughout the attack

- Chapter 3: Add some Colour To Your Play – a chapter about attacking the weakened colour complexes around the king

- Chapter 4: Size Matters – a chapter about sacrificing the material in order to keep the attack going

- Chapter 5: Hit ’em where it hurts – a chapter about attacking your opponent on their weakest point/square

- Chapter 6: Chewing on granite – a chapter about attacking your opponent on their strongest point/square 64

- Chapter 7: Evolution/Revolution – a novel concept I have never stumbled upon prior to reading this book. Evolution is, very simplistically, a concept of building up the position and revolution is the concept of changing the nature of the position. 65

In the final two chapters, the author provides us with fifteen great attacking games and with a set of 50 positions we can solve as exercises, or use as starting positions for training games.

Every chapter consists of a series of deeply annotated and analyzed games. And when I say deeply – I really mean it. Attacking Manual – just like many other Aagaard works – is one of the most deeply annotated books I have ever seen. The number of textual explanations are quite astounding, irrespective of whether we are talking about explanations of concepts at the beginning of each chapter, annotations to the games themselves, or chunks of texts between the games in each chapter, which often talk deeply about the concept studied, while often digressing into other chess-related topics.

One additional aspect I really like about this book is simply – how it looks. As mentioned earlier, one of the things I really like about Quality Chess books is their outline, editing, and structure. I am simply very much a fan of how their books look visually – from font, text outline, diagram size, diagram placement, etc. In general, I do think their books are very pleasurable and enjoyable to read.

So much about the good sides. Alas, one of the big issues I have with this book is its sheer complexity. As mentioned earlier, the level of its depth is astounding, both in terms of the textual explanations and in terms of computer analysis provided. However, while it is definitely desirable in terms of the former, I am not 100% sure if it is desirable when we are talking about the latter. There are quite a few places within the book where the analysis of the subvariations goes on for 15+ moves long, for example on page 211:

I understand how it is very necessary to check everything thoroughly with the modern engines when you are a chess book author in the 21st century, but I am not 100% sure whether it is beneficial to have a major chunk of that analysis presented in a book – especially a book with the title „Manual” with the clear educational/pedagogical purpose.

I understand that such an approach is quite characteristic of all of Aagaard’s books 66 and that it was also endorsed by another great trainer Mark Dvoretsky, but I have personally never enjoyed having a long-computer analysis presented in books and usually don’t bother checking it in greater detail anyway.

The other way in which the complexity manifests itself is the material itself, which is very complex and difficult in itself. Even though the concepts themselves are explained extremely clearly and are simple to grasp, the games provided are definitely NOT. The material is definitely not aimed at lower-rated players and even I have a feeling a lot of it went way above my head.

Of course, in a world constantly pushing for oversimplification and where people are more and more seeking to have everything spoonfed to them, it is refreshing to have a school of thought that insists that the most reliable path toward chess improvement is deep thinking and immersing yourself in the difficult material. 67

However, it can be very tricky to balance between making things too difficult and too easy and I do feel that Aagaard sometimes errs on the side of making things too difficult. 68

Thus, while I do respect the enormous effort that goes into Aagaard’s books and do genuinely think they are high-quality and excellent for higher-rated players, I definitely wouldn’t recommend them to anyone rated, say, below 2000 FIDE.

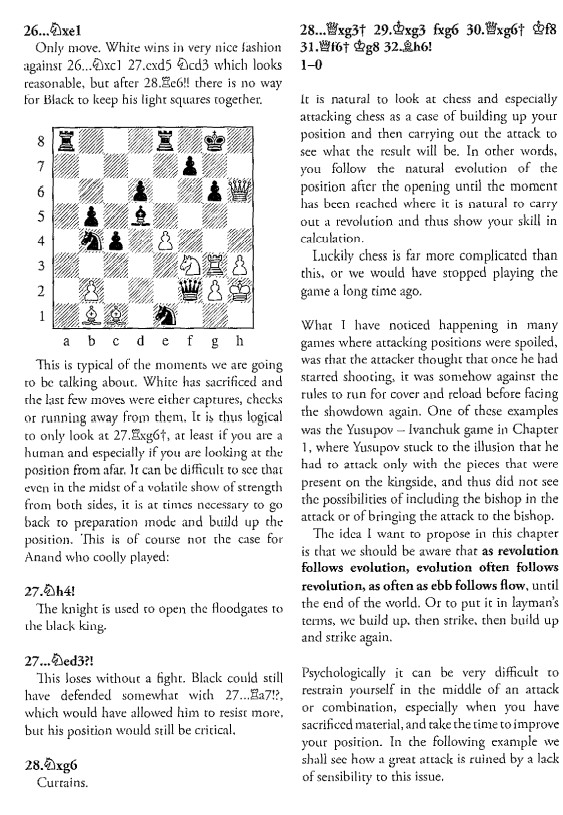

Ivan Sokolov: Sacrifice and Initative: Seize the Moment to Get the Advantage

Continuing with the theme of studying attacking and dynamic play, somewhere in the second half of 2022, at the recommendation of my coach, I also grabbed a copy of the book Sacrifice and Initiative by a well-known former player and another renowned author and coach, GM Ivan Sokolov. 69

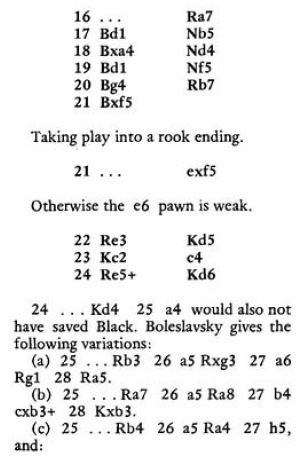

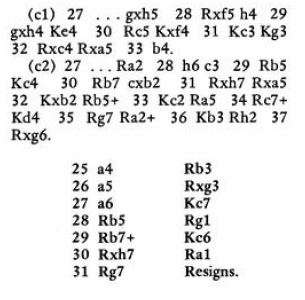

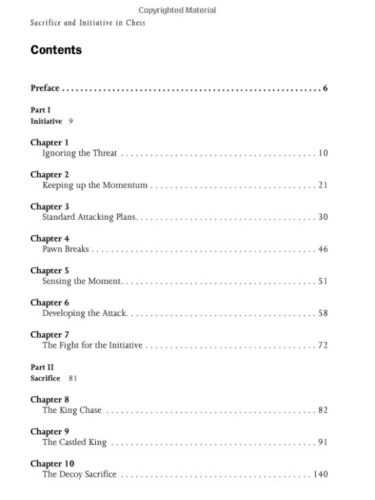

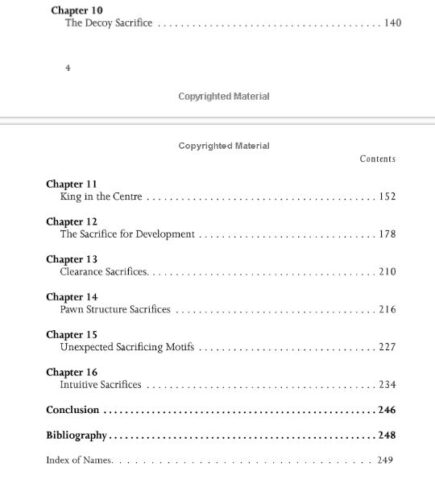

As the title suggests, the book deals with the topics of Sacrifice and Initiative in chess and is divided into two parts. The initial 7 chapters are devoted to the latter, 70 while the subsequent 9 chapters deals with the former:

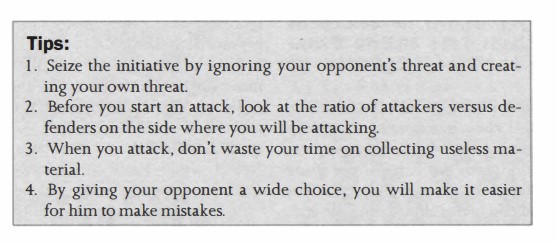

Just like the chapters in the Attacking Manual, every chapter of Sacrifice and Initiative consists of a series of annotated and analyzed games devoted to a certain topic. The selection of the games is again the book’s strong suit, as they very vividly illustrate the concept of the chapter, apart from being quite exciting and interesting. Especially in the first half, Sokolov has done an extremely good job of breaking down such a complex concept such as the initiative into smaller chunks and illustrating them with well-selected games. In that regard, the book was definitely an eye-opener in many ways.

I also think the book did a good job of mentioning important principles at various places – most notably at the beginning of each chapter, but also throughout the games themselves. I especially liked how every chapter was concluded with a small „Tips” window, summarizing the lessons and important principles that have been demonstrated throughout the chapter:

On the other hand, if we disregard the explanation of various principles related to attacking play and handling the initiative, I felt the games themselves left a lot to be desired in terms of their presentation. In contrast to the Attacking Manual which is full of text at every corner, Sacrifice and Initiative is much more lacking in that regard.

First of all, in quite a few places – especially in the subvariations – there are streams of analysis with trees of variations and without a single explanation. Even in the main text of certain games, the author assigns annotation symbols (?, !) to certain moves without explaining why they are so good (or so bad).

Furthermore, even at places where there is textual commentary, the book is full of generic and common chess phrases such as „with compensation”, „This is a blunder”, and „Was the only move” that fail to dig deeper and answer the eternal question bothering club chess players worldwide – WHY.

Mind you, this problem – which was labeled as „Grandmasteritis” in certain circles within the chess community71 – is not at all new, unique, or restricted to this particular book. 72 Yet, it is nevertheless very frustrating to read a book on very complex topics such as Initiative and Sacrifice 73 and constantly ask yourself questions about certain continuations that might have seemed obvious to the author, but that definitely doesn’t seem obvious to yours truly.

Another thing that bothered me somewhat in regard to this book is its overlay/editing. In contrast to the majority of other New In Chess titles, here it is definitely not up to the task, with diagrams being way too small and too few, with text having breaks from one page to another, and with new games starting at the very end of a certain page, and so on.

Thus, for me, Sacrifice and Initiative can be regarded as a diamond in the rough. The topic is extremely interesting and insufficiently covered in the chess literature and the material selection is excellent, which makes it a good choice for higher-rated players who don’t mind doing a lot of work on their own. However, due to the book’s issues and the fact the topic is quite complex, I wouldn’t recommend it to a wider chess audience.

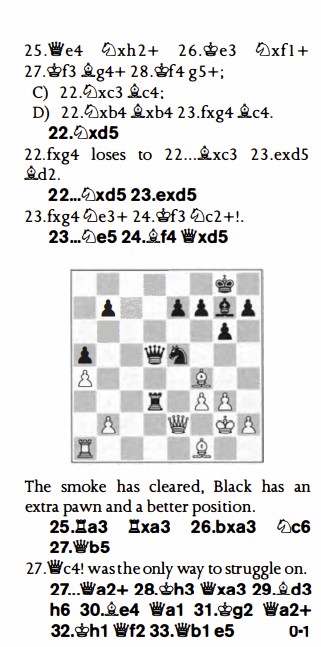

Paul Keres: World Chess Championship 1948

In 1948, after the death of Alexander Alekhine left the chess throne vacant, a historic World Championship tournament was organized to determine his successor and the next world champion. Paul Keres, one of the strongest players never to become a World Champion, was one of the participants (together with Max Euwe, Vasily Smyslov, Samuel Reshevsky, and the ultimate winner, Mikhail Botvinnik). After the tournament, Keres spent several months analyzing the games and writing the tournament book. 74

Thus, this book features Keres’ round-by-round analysis and commentary of every single game played in that tournament. I found the level and amount of annotations quite remarkable. Almost every few moves, Keres offers his unique insights and opinions about different types of positions. Apart from the opportunity to hear the thoughts of such a legend of the game, I also found some of these comments quite instructive. Especially when they are referring to positional concepts or strategical themes, as I feel the difference in pure elementary understanding of the game between the old masters and modern grandmasters is not as pronounced as, say, opening knowledge or calculation ability.

Sure, as with almost all old books – the accuracy of analysis does not fully stand the test of time and the all-seeing-eye of the chess engines. But somehow, I didn’t find this aspect so bothersome with this book as, say, with Endgame Strategy. Maybe it is my bias for Keres, maybe it is the fact that this book is much more densely annotated or maybe I consider the accuracy of analysis more important in a book that is supposed to be an instructive manual and not a game collection.

The aspect of the book that didn’t appeal to me as much was the absence of any actual non-chess content, such as behind-the-scenes events, Keres’ own impressions and struggles, his experience with preparation, his impression of other players, etc. It is very understandable he wasn’t really willing to express too many opinions given the entire political climate and the context of the times, but I feel it is a great pity that the book lacks a little bit more personality. 75

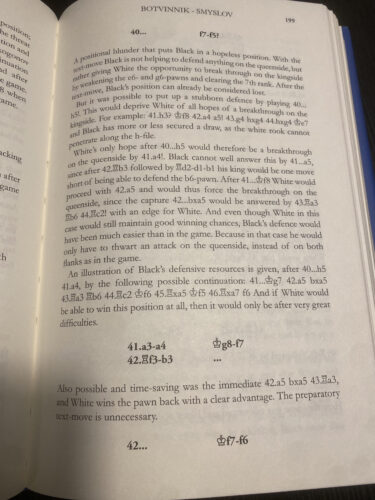

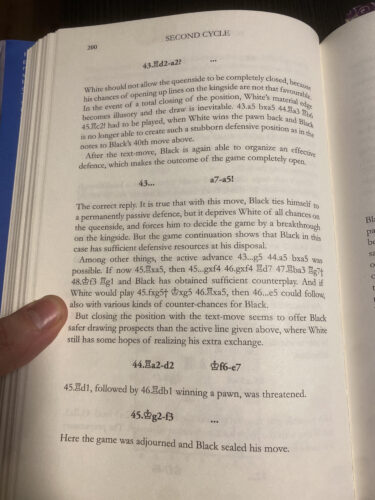

Another drawback of Keres’ books is the usual problem of chess books – lack of diagrams which makes it very difficult to read the book without the board. This lack of diagrams is especially bothersome given that the book has extremely large font and margins, due to which a single game often spans across multiple pages. For example, take a look at pages 199-200 of the book:

Last but not least – I am not really sure how instructive this book is purely from the „chess improvement” perspective. I do feel it might have something to offer to players up to a certain rating level, but in general, I regard it as a primarily historic, rather than instructive, work.

Thus, if you are looking for a nice game collection written by one of the strongest players of the time, this book might be for you!

Danny Kopec: Mastering The Sicilian

Somewhere at the beginning of 2021, I decided to do significant work on my opening repertoire. Aside from adding Grünfeld against 1.d4, I also decided to expand my repertoire against 1.e4 and stop playing the Modern exclusively. Apart from returning to my old love Alekhine, I also figured I might want to add a real, healthy opening to the mix. An opening that is more mainstream, yet still leads to the combative play. Thus, picking up 1…c5 was a natural choice – especially since Sicilian structures can also often be reached via the Modern move order.

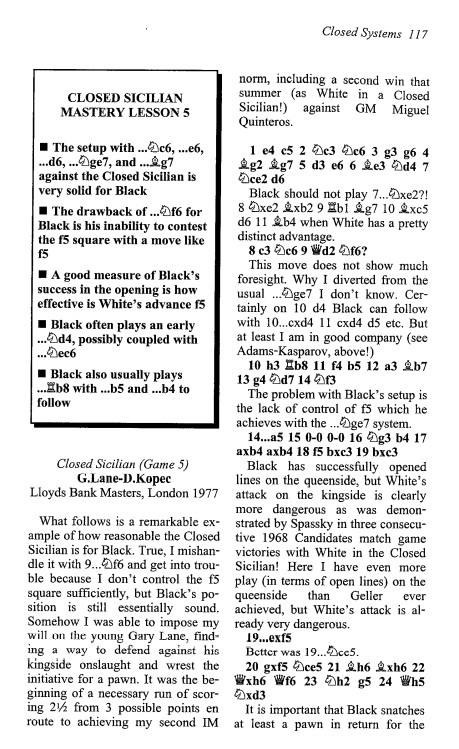

However, similarly, as with Grünfeld, I realized that I should probably study some middlegames and typical games instead of solely clicking through the lines in Chessbase/Movetrainer. And even though I did get the impression that the Sicilian structures are much better covered in the chess literature than the Grünfeld structures, 76 I was still happy when my coach recommended the book Mastering The Sicilian by American International Master Danny Kopec and I promptly got down to reading it.

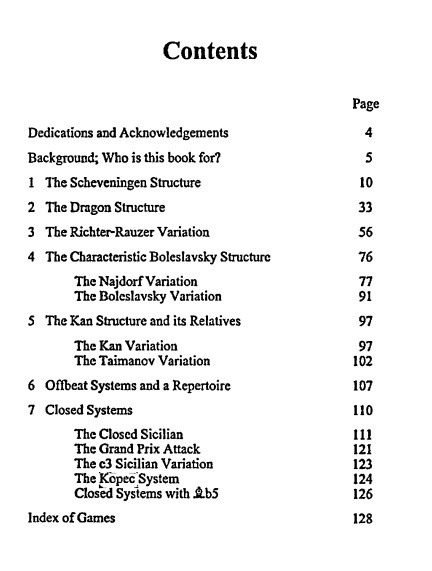

Mastering the Sicilian is basically a book on Sicilian Structures. In the first 5 chapters, the author covers some of the most common Sicilian structures out there, as follows:

- The Scheveningen Structure

- The Dragon Structure

- The Rauzer Structure

- The Boleslavsky Structure

- The Kan Structure

The final two chapters are devoted to rare Sicilians and provide some insight into systems such as Closed Sicilian, Grand Prix, etc. Thus, even though this book is aimed at Sicilian players, it is not necessary for a Sicilian player to read every chapter, but only that refer to structures related to the variation of the Sicilian you play. Thus, if you are a Dragon player, you can probably only focus on the second and the seventh chapter of the book and ignore the rest.

As you might have figured out by now, this book is not a theoretical manual, but rather a middlegame book. Every chapter starts with a relatively detailed elaboration of the structure at hand and consists of a set of model games featuring that very structure displaying a variety of possible plans and ideas for both sides.

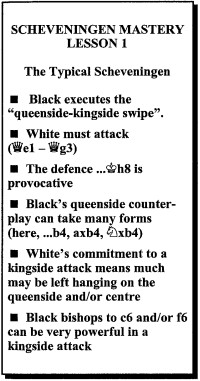

As a matter of fact, I think this emphasis on typical plans and ideas is the best thing about this book. Before every game, the author provides the reader with the so-called „Mastery Lesson” box, outlining the most important and instructive moments, maneuvers, and themes for every single game.

I think such a streamlined approach is absolutely necessary for a „structure-oriented” book. It is not a coincidence that the aforementioned Chess Structures: A Grandmaster Guide implements a very similar approach.

As for the annotations and the analysis of the games themselves, they leave a lot to be desired. The commentary is very sparse, both in terms of density (how many moves are actually annotated) and the number of words used. Most commentary resorts to the typical „XYZ is equal” grandmaster remarks or to the standard „let me give a long variation with a lot of moves and no explanations to prove a point”. Since I knew from the very start I want to focus on ideas and play through a bunch of games without necessarily being concerned by the accuracy of the analysis, I didn’t even bother to check it too thoroughly, but one does get the impression that the book was scraped hastily, somewhat lazily and without too much attention to details.

This haste is especially apparent if we consider the general size of the book (only ~130 pages), the fact that the sixth chapter devoted to rare 2nd moves is only 3 pages long, or if we consider the visual design of the book. The distribution of the diagram, the outline of the elements on pages, and the general visual identity of the book are simply atrocious and I can’t be left wondering where on Earth was the editorial input in regard to these matters?

Thus, even though the book features a nice collection of games and contains instructive lessons for a Sicilian player, it leaves a lot to be desired. It is definitely not sufficient in itself to help you „Master the Sicilian”. 77

If I were to rate it, I would hardly give it more than, say, 3 stars out of 5. Even though you might find a lot of value in it if you are a Sicilian player just starting your journey through the 1.e4 c5 waters, I think you are better off buying another designated Sicilian book (say, Starting Out: The Sicilian) or another book featuring the Sicilian structure (such as the aforementioned Chess Structures: A Grandmaster Guide).

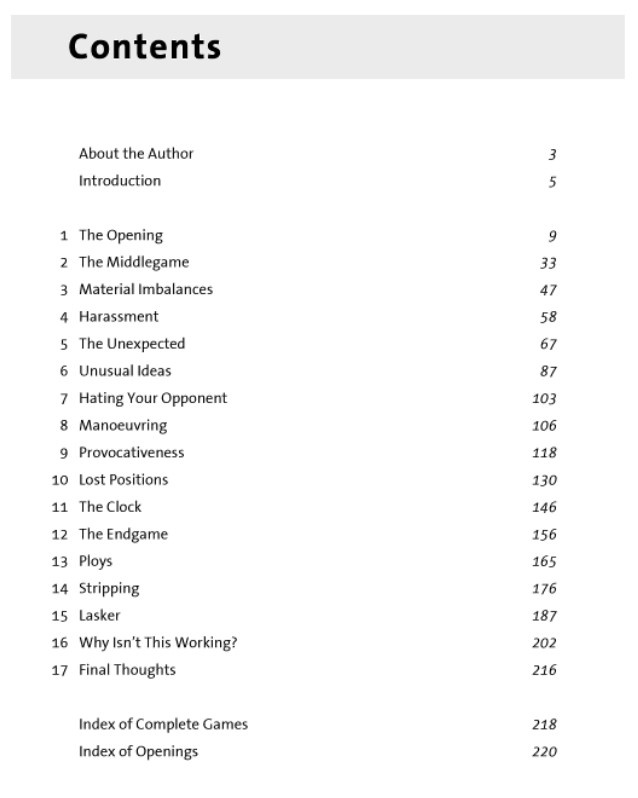

James Schuyler: Your Opponent Is Overrated

In episode 148 of the „King Of The Chess Podcasts” – The Perpetual Chess Podcast, an old friend of the blog and a renowned Chessable author Kamil Plichta mentioned that the book Your Opponent Is Overrated is one of his favorite chess books of all time. Ever since it has been on my wishlist, and this year I finally got around to reading it.

This book is all about the psychology of chess and how to use it to your advantage to force your opponent to make a mistake (which is why the subtitle of the book is A Practical Guide To Inducing Errors). Over the course of 17 chapters, FM James Schuyler talks about different topics such as how to make your opponent uncomfortable straight out of the opening, how to handle lost positions, how to prepare tactical ideas in a manner where your opponent is likely to miss them, how to play in „provocative” manner, about the controversial topic of „using the clock to your advantage” and much more.

The goal of the book is, basically, to provide you with ideas, tools, and a mindset that will help you become a more successful practical player. It is definitely a very fresh book dealing with topics that are rarely covered in chess literature. 78 I do genuinely believe every chess player would benefit from learning how to be more resilient in lost positions 79 or not being too much attached to the objective value of the chess opening – even in a classical game. 80 I feel players with limited/no OTB experience would particularly benefit from reading this book as it can teach them techniques and concepts that are usually learned mainly through experience.

On the other hand, I do want to emphasize that, in my opinion, there is the danger of overestimating the value of the psychological approach to the game. I do feel such an approach can sometimes make you overconfident and lose your objectivity. And even though the author does occasionally tackle this conundrum and even devotes an entire chapter to the concept of „overpressing”, I do feel it is necessary to keep an open mind and take everything written „cum grano salis”.

I, for one, would say that having an opening like Latvian Gambit as one of your main weapons against 1.e4 and employing it against master-level opposition in classical games in 2022 does fall in the „overstepping the risk” category. I feel that the author very often goes to extremes where moderation is required in order to illustrate a certain concept and that it might give some wrong ideas to the (inexperienced) reader.

But leaving that aside, Your Opponent Is Overrated is definitely a very fresh and original book that I would recommend every chess player to read at least once during their career.

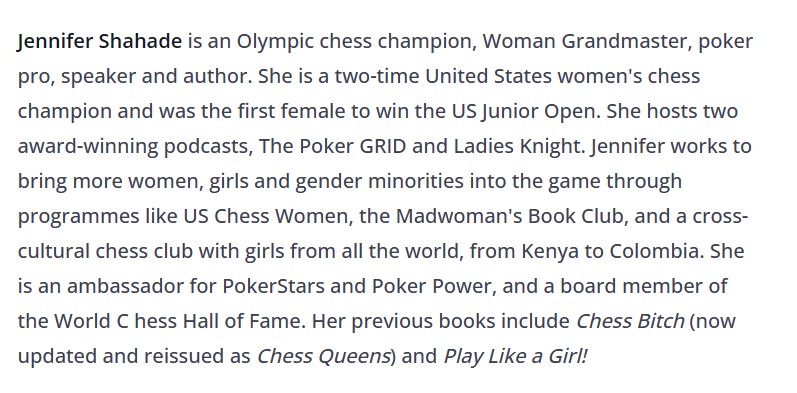

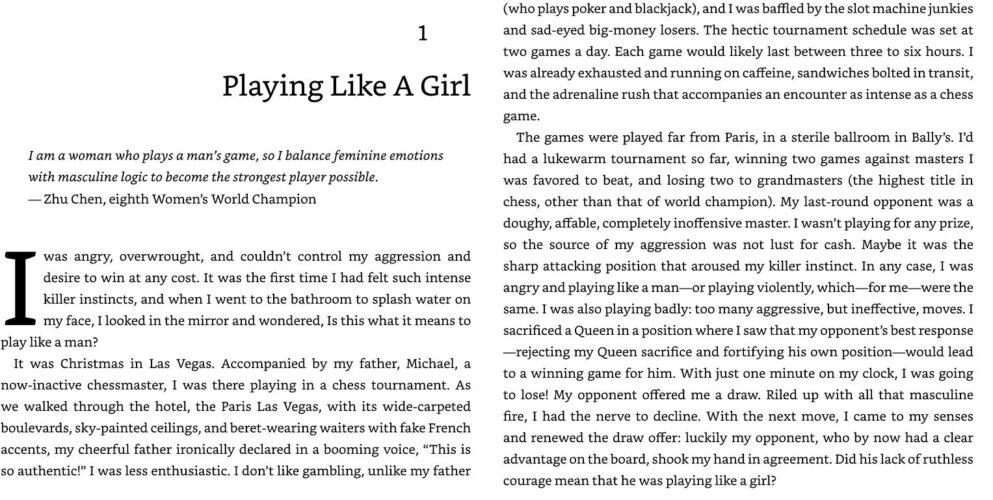

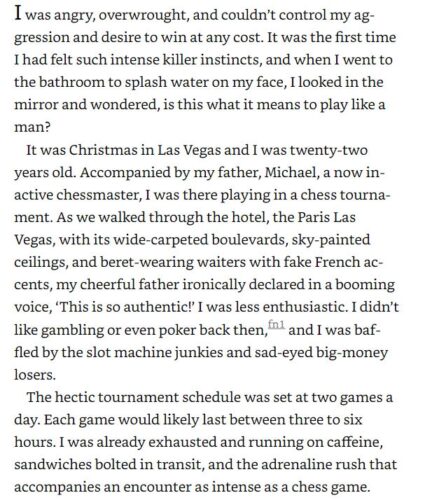

Jennifer Shahade: Chess Queens: The True Story of a Chess Champion and the Greatest Female Players of All Time

WGM Jennifer Shahade, the current Women’s Program Director of the US Chess Federation is probably one of the biggest ambassadors of our game and advocates for female inclusivity and dignity within the chess world. 81 Some older readers might remember that her very first book titled Chess Bitch: Women In The Ultimate Intellectual Sport, devoted to great female chess players of the past (and present) was featured and reviewed in my previous post on the list of best chess books I read back in 2020.

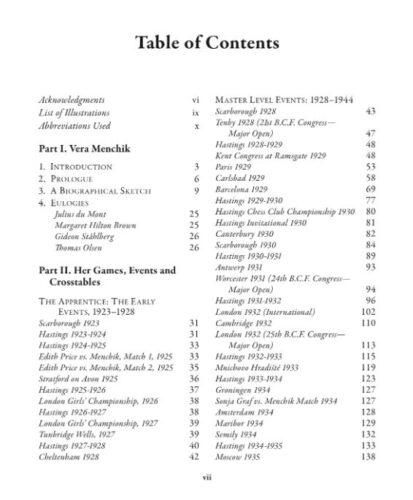

Chess Queens is WGM Shahade’s latest publication and is a follow-up to the Chess Bitch devoted to the very same topic. In the book, WGM Shahade talks in great detail about great female chess players of the past (and present) – from the early trailblazers such as Vera Menchik and Sonja Graf, via great Soviet and Georgian players of the 1950s-1980s period, to more modern heroines such as the Polgar sisters or great female Chinese players of the last 30 years. In selected chapters, she also talks about her own experience as a female in the chess world, the challenges she had to endure, and the sexism she had to face.

Just like Chess Bitch, the content of this book is excellent. In a world where too little is written from the female perspective and about female chess players, books such as this one are not only fresh and interesting but also very necessary. Reading about the fates of these great chess players, hearing about the challenges and difficulties they had to endure, and realizing female chess players have to think about things most male players never even consider will hopefully more male players aware of all these issues and more sympathetic toward the „female issue” in chess. 82

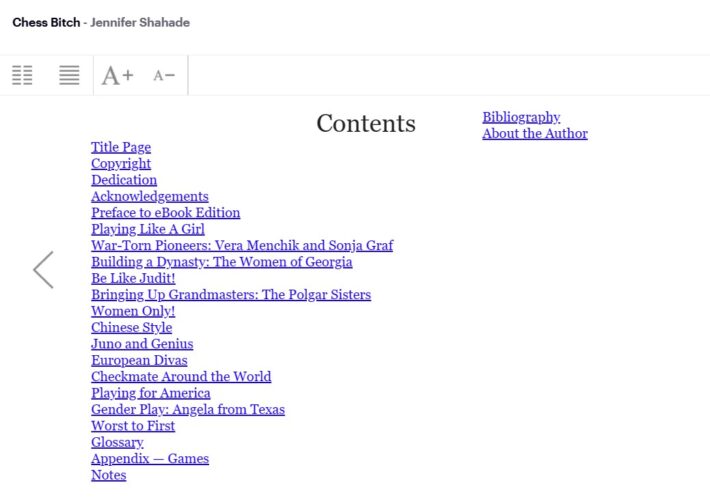

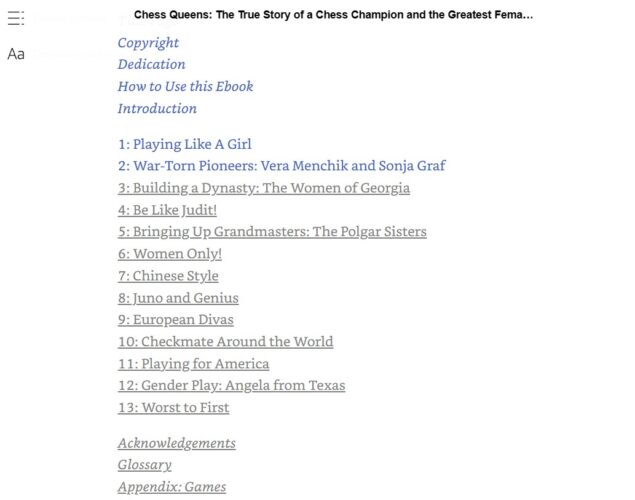

However, due to the big overlap in topics between Chess Queens and Chess Bitch, a lot of people were wondering – what are the differences between the two books? Is Chess Queens a completely new work completely independent of Chess Bitch, or more of an update and revision of the existing book?

This question was discussed in some detail before Chess Queens was released and the general messaging was that this book is an updated and revised, 2022 edition of Chess Bitch. This was confirmed by Jen herself in episode 269 of the Perpetual Chess, where she described in great detail how and why Chess Queens happened to be. The similarity with the previous book is clearly emphasized in the Introductory chapter:

but it is also very obvious if one takes a look at the chapter distribution of both books:

(The table of contents of Chess Bitch can be seen on the left, while the table of contents of Chess Queens can be seen on the right)

I felt this fact could have been emphasized more clearly in marketing texts on the websites of different publishers. For example, the product description on Amazon.com or on Ichess.net don’t mention Chess Bitch at all, while a book review on Chessbase also doesn’t make it very clear given that it states that:

„After “Chess Bitch” she has now published another book on women’s chess, “Chess Queens”.”

The only place where I have seen Chess Bitch clearly mentioned and referenced is on the New In Chess website, where it is stated that:

„Jennifer’s previous books include Chess Bitch (now updated and reissued as Chess Queens)”

It is true that this info is presented in the section dedicated to the author and not the book itself, but at least it is present – which is what can’t be said about the author information on Amazon:

As for the content – I haven’t really done a detailed page-by-page analysis to compare the differences. I recognized places where the book was updated, e.g. sections of the book mentioning new and relevant studies from more recent years or the chapter „Chinese Style” that does talk about Hou Yifan – the 2nd best female player ever who wasn’t even around back in 2005 when Chess Bitch was first published.

But I also recognized many parts/paragraphs that are absolutely identical to paragraphs/parts also present in Chess Bitch. Overall, while I was reading Chess Queens I had a very strong feeling of deja vu and didn’t really have a feeling I am reading a fundamentally different book.

(The opening chapter from the Chess Bitch (on the left) compared to the opening chapter from the Chess Queens (on the right) )

Therefore, if you have read Chess Bitch in the past, I wouldn’t recommend you to also dive deep into Chess Queens, as I don’t feel the fundamental difference between the books is sufficient to justify spending the money anew.

But if you haven’t read any of the two, I can only wholeheartedly recommend Chess Queens, because all the points I made in my review of Chess Bitch about the value, relevance, and importance of the book still stand.

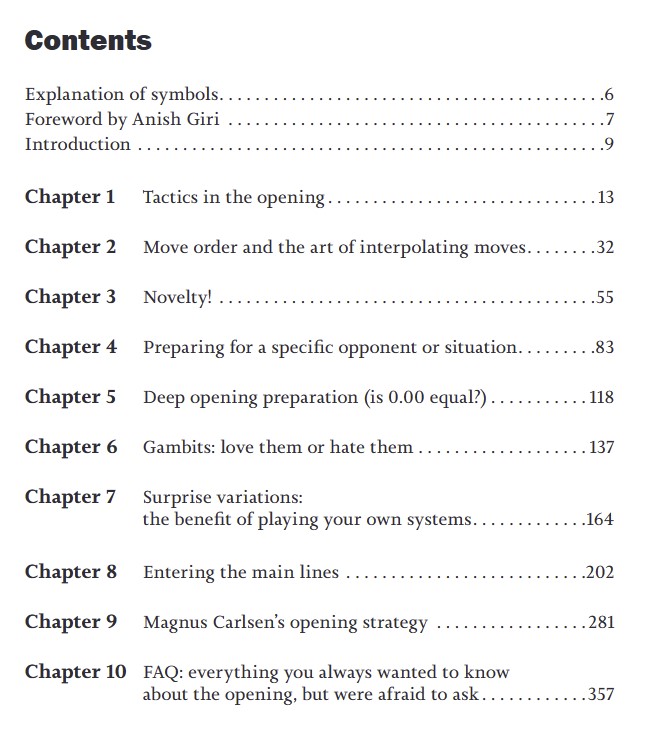

Jeroen Bosch: How To Outprepare Your Opponent – A Complete Guide to Successful Chess Opening Preparation

As mentioned previously, 2022 was really a great year for chess books, during which an unprecedented number of interesting and fresh books were published.

One book of particular interest to the author of these lines was the book titled How To Outprepare Your Opponent, written by Jeroen Bosch and published by New In Chess in June 2022.

For those of you who are not familiar with Jeroen Bosch, he is a strong International Master who is very well regarded as a theoretician and opening specialist. He has been the coach of the Dutch national female team and is also a long-standing contributor to the New In Chess Magazine where he has been writing a column titled Secrets of Opening Surprises (SOS).

Thus, when I heard he is writing a book on the topic of opening preparation, I was very excited and knew I would very likely buy the book at the first opportunity. 83

So, how does one go about writing about the opening preparation? After the somewhat introductory chapter about the tactics in the opening, Bosch examines a number of extremely important practical topics related to the openings and opening preparation. He also tries to answer/discuss some „eternal” questions every tournament player is either constantly pondering, or not pondering enough at all.

Over the course of the ten chapters, some of the topics that are considered are:

- Importance of move-orders and transpositions in your opening play/opening preparation

- Value of novelties and dangers of overestimating them

- Preparing for a specific opponent

- Understanding that not all positions where the engine gives „0.00” are necessarily equal

- Are gambits playable in the 21st century? How to determine whether they are and how to decide when to employ them?

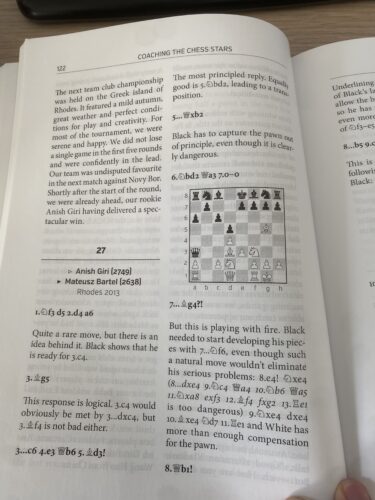

- The benefits of playing the mainlines compared to playing the sidelines