Warning: Long post incoming! Leave all hope ye who enter!

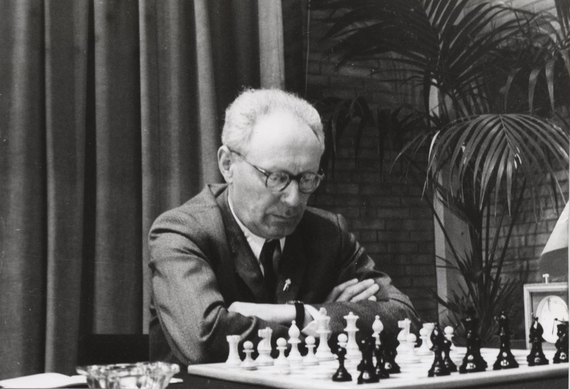

Last week, a very intriguing question, titled: Is it fair to say that Mikhail Botvinnik is the “bad guy” of modern chess? appeared on the Q&A website Quora.

I ventured to provide an answer and was very satisfied with the result. Without false modesty, it was one of the better researched and coherent pieces of writing I did lately.

I think I have managed to portray Botvinnik’s complex character to a certain degree.

I was so satisfied, I decided to share it on this blog as well.

Hope you will enjoy it.

The answer depends on your definition of the term “bad guy”.

He wasn’t evil.

But he wasn’t a particularly nice guy either.

Allow me to elaborate.

First of all, many chess players (me included) don’t like Mikhail Moiseeich the sixth.

For the most part of his life, Botvinnik was interested only in one thing.

Himself.

His personal interests came first and foremost. He worked toward achieving his goals with his famous logic and consistency… and disregarded other people in the process.

He himself admitted that openly. One of his books is titled Achieving the aim. The following quote…of his own… is a very accurate description of him as a person:

I was lucky in life. As a rule, my personal interests coincided with the interests of society – it is this that probably constitutes genuine happiness.

And I was not alone – in the fight for the interests of society I had support. But not all with whom I associated were as fortunate as I was.

The personal interest of some people differed from those of society and these people interfered with my work. It was then that conflicts arose.

(Source: Garry Kasparov – On My Great Predecessors, Part II)

How did this “interest in himself” and “disregard of other people” manifest? There are several examples:

Botvinnik – Levenfish match for the title of the absolute USSR Champion, 1937

In 1935 and 1937, Botvinnik skipped the USSR Championships. In his absence, Grigory Levenfish won the double crown.

There was one problem. The greatest tournament of those times, AVRO 1938, was getting close. Every country was supposed to send their best player. Levenfish had every right to expect he would be the chosen one.

There was just one problem – Botvinnik was more suitable for the role of the leader of the USSR chess. Younger than Levenfish, a staunch communist, successful engineer.

So he decided to challenge Levenfish to a match of the absolute USSR champion. Naturally, he got the support, since “his personal interests coincided with the interests of society”:

Botvinnik claimed that Nikolai Vasilyevich Krylenko was furious with him for missing the tournament and forced him into the match with the new Soviet champion.

Levenfish claimed that Botvinnik challenged him personally without any persuasion.

(Source: Botvinnik – Levenfish (1937) )

Alas, after a sharp battle, the match ended in a draw. Botvinnik didn’t manage to prove he was stronger than Levenfish. In Achieving the Aim, Botvinnik wrote that:

“The outcome of the match was awkward for Grigoriev not only because my opponent was helped by a whole brigade of masters. At that time Soviet players needed a leader on whom they could rest their hopes of winning the world championship, yet here was a new champion – Levenfish.

The situation was a muddled one and the match result only made matters worse.”

Just to make it clear. You don’t participate in a championship. You gain the privilege to challenge the champion. You don’t beat the champion. And you say the situation is a muddled one?

Entitlement at its finest! Botvinnik wrote such things without a hint of embarrassment.

Unfortunately for Levenfish, the Soviet authorities agreed with Botvinnik’s point of view. They solved the Gordian knot quite handily – they decided to send Botvinnik to AVRO:

Levenfish had probably expected to represent USSR in the next big international tournament [that was AVRO 1938].

But… “Levenfish tried to insist that he represent the Soviet Union, but he was not supported and I was assigned to play in the AVRO tournament”. [in Botvinnik’s Achieving the Aim, p. 65].

Levenfish had written about this in his Selected games and memories, 1967:

“I thought that my victories in the ninth and tenth USSR Championships and the draw in my match with Botvinnik would give me the right to participate in the AVRO-tournament. However, contrary to my hopes, I was not sent to this tournament. My condition could be defined as a moral knock-out. All my efforts of the preceding years had been in vain. I felt confident in my powers, and I would undoubtedly have competed honorably in the tournament. But I was 49 years old, and it was obvious that the coming years would tell adversely on the strength of my play. I was losing the last opportunity to display my worth. I gave up my chess career as lost, and although subsequently I participated in a few events, only in rare cases did I play with enthusiasm and competitive interest.”

(Sources: Garry Kasparov – On My Great Predecessors, Part II and Grigory Levenfish vs Mikhail Botvinnik, USSR 1937… in the shade of world chess championship )

AVRO 1938 – Aftermath

So, Botvinnik was sent to the historic AVRO tournament 1938. The strongest chess players of the time, including the World Champion Alexander Alekhine, were invited.

The tournament was supposed to serve as a sort of Candidates tournament. The winner of such a prestigious event would be regarded as the worthy challenger for the World Championship.

Although Botvinnik distinguished himself with victories against Alekhine and Capablanca (the latter, featuring the famous Ba3 shot, being particularly impressive), he fell short of the first prize – Paul Keres and Reuben Fine shared the victory.

After his victory, Keres promptly scheduled a meeting with Alekhine and expected to arrange the details of the future match. However, he was forestalled by … Botvinnik, who decided to disregard the pre-tournament arrangements.

In the Great Predecessors, I have read somewhere that he “considered he deserved a shot at the title after his victories over Capa and Alekhine”.

(Much entitlement. So wow!)

Alekhine was reluctant to sign any written arrangement with Keres. Keres left, the AVRO company refused to meet Alekhine’s demands and the question of the next challenger was left open.

(I am not quite sure what Fine was doing and whether he negotiated with Alekhine as well, though. Does anyone know?)

(Also, this was not the last time Keres’ suffering brought Botvinnik benefits. I have written more about Paul the Eternal Second in one of my Quora answers Vjekoslav Nemec’s answer to Who is the most unfortunate chess player in history? and in a separate article on this blog)

Botvinnik – Tal Return Match 1961

In 1960, Mikhail Tal beat Botvinnik convincingly in their World Championship Match. According to the match clause, Botvinnik was guaranteed the right to a Return Match. Blinded by Tal’s brilliant play, his seconds weren’t convinced it is such a good idea.

Botvinnik, being the stubborn and consistent man he was,

„[…] realized that the return match definitely had to be played!“

Almost immediately after the 1960 match, he started seriously preparing for the upcoming clash.

Tal, on the other hand, was far from his best form. Already back then, his lifestyle started taking its toll. Being a heavy smoker and a drinker, he fell seriously ill just before the match. Riga doctors advised him to defer the start of the match by a month.

USSR Sports Committee was ready to agree, but Botvinnik demanded (!) that Tal should come to Moscow for an official medical examination. Upon hearing this, Tal apparently said:

„Never mind, I’ll beat him as it is!“.

As we all know, this turned out to be a crucial mistake – Tal lost the match quite convincingly.

But it is interesting to observe how Botvinnik continued to behave like a champion and make demands even after losing the title…

Not to mention how non-empathic and selfish his demand was in the first place.

Treatment of other people

Botvinnik saw people around him purely as a means of achieving his own end.

I remember a story from Garry Kasparov’s my Great Predecessors. I will paraphrase it here.

During a tournament, Botvinnik adjourned a game.

He sealed his secret move in his envelope.

One of his seconds (which I believe was Ragozin, although I am not 100% sure – VN), immediately started to analyze the game. By evening, he found a nice idea, so he knocked on the door of Botvinnik’s room to demonstrate it. Botvinnik told him to show it later.

The next day, Ragozin tried again during the breakfast. Botvinnik listened to him attentively. Then the car with the driver arrived and picked them both up. During the ride, Ragozin kept explaining. Botvinnik simply nodded.

Finally, they arrived at the playing hall. As they were exiting the car, Botvinnik suddenly remarked: “You know, Viacheslav, I sealed a different move!”

This suspicion toward those closest to him was characteristic of Botvinnik. He was always alert and perceived everyone as a threat. It is not surprising he played without seconds for most of his chess career.

Moreover, from his annotations (and other writing) it seems he never really appreciated and admired… well, anyone.

This is not just my opinion. From an interview with Yuri Averbakh:

Q: There’s a legend that Botvinnik had a very difficult personality. Is that true?

A: I’ll share with you a story that Baturinsky told me. When Botvinnik had only a first category and played against the older St. Petersburg players, he would write derisive epithets about them into his notebook. “Old hooker” was the mildest of them. That’s characteristic of him: he thought very skeptically of people.

I remember he was also very dismissive of Tolush, the first trainer of Spassky, famed for his combinative and (irregular) attacks. According to Kasparov, he several times told him something along “If you continue to play like this, you will become the next Tolush/Larsen/Taimanov”.

As if becoming the next Botvinnik is that much better.

Okay, now that I have ranted for quite a bit, let’s be fair and take a look at the other side of the story.

Nothing in life, (apart from the squares of the chessboard) is white or black. Although he had a lot of flaws Botvinnik definitely had his good sides.

First of all, after losing the match in 1963 against Petrosian, Botvinnik decided to retire from World Championship competition (even though he had a right to a Return Match). Cynics would say he feared another defeat. But even if he was, he was simply being realistic and objective about his playing strength (see below).

But I also think he was honest when he said he wants to give chances to younger generations.

Secondly, his foundation of the Botvinnik Chess School in 1963 is admirable. We could debate whether he did it out of altruism or to feel relevant (and important) after the end of his competitive career.

But that is beside the point – Botvinnik School raised several generations of top chess players. Anatoly Karpov, Garry Kasparov, Vladimir Kramnik and Alexei Shirov all attended sessions there, among others.

More importantly, Botvinnik didn’t just give his name to the school. He was ACTIVELY engaged there. He gave lectures, he advised his students before and during competitions and he helped them a lot off-the-board.

He was the one who convinced the organizers of the Banja Luka 1979 tournament to invite an unknown Soviet Master Garry Kasparov.

He dedicated himself completely to passing chess knowledge to young generations.

Yes, he was fairly strict. I recall a story about how he was asked to evaluate Ljubomir Ljubojević, a talented Yugoslavian Grandmaster. At one session in the school, Botvinnik asked him whether he analyzes his own games.

“What for?” asked Ljubo in genuine surprise.

Then I realized nothing worthwhile will come out of him.

However, in his Predecessors, Kasparov writes that, behind all the strictness, there was a warm man who deeply cared about pupils.

And who loved chess with his whole heart.

According to Lev Khariton:

Botvinnik’s apparent coldness and arrogance were, in my opinion, his defence not only at the chessboard, but in life as well when he had to prove his supremacy. But as a chess player, he brought up many pupils who became strong masters and grandmasters. Many leading trainers – M.Dvoretsky, A.Nikitin, A.Bykhovsky and others – have more than once relied on Botvinnik’s advice and experience.

(Source: Lev Khariton: English Lessons (Remembering M.M.Botvinnik))

In the same article, Lev Khariton praises Botvinnik for his modesty and objectivity. And indeed, he is virtually the first chess annotator (apart from maybe Alekhine) who searched for the truth in his games. Apparently, he didn’t have problems in admitting he was wrong:

Botvinnik’s modesty was proverbial. You felt it in his manners, in his everyday life (he was washing up and shopping himself!), in the simplicity of his apartment. Me first chess teacher the late and unforgettable Yuri Brazilsky who worked as an editor of chess literature of the Fizkultura and Sport publishers in Moscow, happened to collaborate with Botvinnik editing his chess books. Brazilsky told me with what trepidation and respect he used to watch Botvinnik analysing chess positions. He was particularly amazed when Botvinnik admitted having made some blunders or mistakes in his commentaries.

How often he admitted he was wrong is another thing. But this stubbornness and conviction he is often right also had a positive side – Botvinnik was very principled. His sense of justice was developed and he detested authority of any kind:

When in 1976 after Korchnoi’s defection almost all Soviet grandmasters signed the letter against the “traitor”, Botvinnik was also asked to put down his signature. But at this moment Botvinnik really made the move of his life, the move explaining his supremacy in chess for many years.

He said that he wanted to write his own letter denouncing Korchnoi. In my opinion, Botvinnik was well aware that for the bureaucrats of the 70s he was a figure of the past and nobody would ever give him this “privilege”.

And so, his name cannot be found under this shameful document.

This immortal quote also comes to mind.

I believe thinking with your own head is a very important trait – especially today when we are being bombarded by information.

When it is hard to determine what is a lie. And what is the truth.

Finally, the reason Botvinnik is often perceived as a “bad guy” is simply because the chess community is heavily biased (me included).

I think people often underestimate his results during the say 1935–1948 period and simply watch him through his World Championship matches. Common complaints include:

- Oh, but he drew his two matches against Bronstein and Smyslov, he could never win a World Championship Match

- Oh, but he had a right to Return Match every time, it is easy to play like that

- Oh, but he didn’t win any major competitions in that period

Yes, I will be the first to say Botvinnik shouldn’t have a place in the GOAT debate. But I think it is not fair to disregard his results completely. For a long time, he was number one (perhaps with Keres). In his later years, he was an incredible match player. And he DID solve the Tal-enigma.

(Also, don’t forget he was also affected by WWII – lack of competitions surely hindered his development as a chess player!)

He is not considered as a Patriarch of the Soviet Chess for nothing. His games are instructive, he was the first to pay attention to opening preparation, to develop professional tournament regime, he discovered multiple original plans (e.g. advance of the f-pawn in isolated queen pawn positions), etc…

Also, I think the fact he was a staunch communist in the Stalin era didn’t help his image. I think many people, especially in the west, see him through this lens.

He was definitely not the first (nor the last) chess player with a big ego and disregard for other people around him. But he is the one that gets chastized for it the most. And I think it has a lot to do with his political preferences. And the system behind him.

For instance, Robert James Fischer had several similar traits like Botvinnik. Competitiveness above all. Entitlement. Conviction in his own superiority. Paranoia and suspicion toward everyone around him. Disregarding other people’s needs. Treating those around him badly. Etc.

However, Fischer is very often praised. Simply because he grew up in such an environment. In the era of individualism. Of pursuit of the American Dream.

Of course, Fischer did most of the work on his own. Botvinnik had the support of the system. But that is relevant as long as we are talking about them as chess players.

Not when we are talking about them as humans.

As humans, they had many things in common.

To conclude, I guess it is fair to say Botvinnik was the “bad guy” of the modern chess.

But it is also fair to provide arguments. And to explain what “bad guy” actually means.

Because Botvinnik was not “bad” in a sense he was inherently evil.

He just sometimes behaved like an asshole.

But – don’t we all?

Other articles on this blog featuring Botvinnik:

- Botvinnik’s best chess games

- Best Players Never To Become World Champion, Part Two: Paul Keres

- World Chess Championship Tournament 1948

- Botvinnik – Bronstein, 1951

- Botvinnik – Smyslov, 1954

- Botvinnik – Smyslov, 1957

- Botvinnik – Smyslov, 1958

- Botvinnik – Tal, 1960

- Botvinnik – Tal, 1961

- Botvinnik – Petrosian, 1963