After Capablanca’s victory against Lasker in 1921, the latter claim he will no longer participate in World Championship matches. The first player to challenge Capablanca, immediately in 1921, was Akiba Rubinstein, the Polish champion and one of the leading players of the 1900s and early 1910s. Very soon afterwards, Alexander Alekhine, the leading Russian master, also issued his challenge.

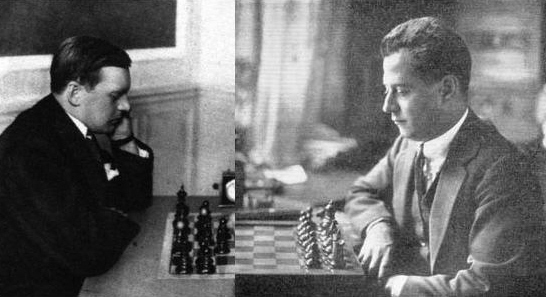

Alekhine, born in Moscow in 1892, appeared on an international scene in 1912, when he won the strong 8th Nordic championship in Stockholm with 8.5/10. During the pre-war years, he won a number of „weaker“ tournaments, and confirmed his status as one of the best players in the world by taking the third place in the iconic St. Petersburg 1914 tournament, just behind Capablanca and Lasker.

After the war, Alekhine continued developing his chess skills further. After winning international tournaments in Budapest, Triberg and the Hague in 1921, he issued a letter to Capablanca, stating that:

„I should be grateful if you would consider the present letter as an official challenge to a match for the World Chess Championship“.

Alekhine was aware Rubinstein’s challenge came before his and he addressed this issue in his letter as well:

„Nonetheless, since I have read that, on the basis of his pre—War successes (in 1912), the Polish master Rubinstein has already sent you a similar challenge and that you have accepted it, I should be quite ready, if that match has already been fixed for a more or less precise date, to await its conclusion to have the honor and pleasure of measuring myself against you. „

In this situation, Dutch chess officials tried organizing a „Candidates match“ between Alekhine and Rubinstein. Although both players agreed to a match, due to some very murky behaviour by Alekhine, who in January 1922 claimed, Rubinstein ended up in the sanitarium due to mental illness. It would appear this claim was false and there was nothing wrong with Rubinstein’s health.

At the end of 1921, Capablanca wrote his version of the „rules“ for the World Chess Championship. He introduced them during the London 1922 tournament (which he won convincingly). The so-called „London Rules“ were signed by the leading masters of the world – top eight prize winners of the London tournament – Maroczy, Reti, Rubinstein, Alekhine, Vidmar, Tartakower and Bogoljubow.

The most important point of the London rules was the so-called „Golden Wall“. The rules envisioned that the world champion should be obliged to defend his title only if the challenger manages to raise 10000$ for the prize fund.

During the London Tournament, Capablanca and Rubinstein agreed their potential match would take place only in 1923. However, it was precisely due to the „Golden Wall“ rule that their match never took place; Rubinstein was simply unable to collect this enormous sum of money.

Neither were Capablanca’s next challengers – Marshall in 1923 and Nimzowitsch in 1926 able to do so. Alekhine was also unable to find financial backers until 1926 when Argentine Chess Federation offered to sponsor the match. Capablanca agreed to the match, but only if Nimzowitsch, whose challenge was pending at a time, would be unable to raise the funds until January 1, 1927. Nimzowitsch was unable to do so, and Alekhine – Capablanca 1927 match was finally agreed.

Before the match, Capablanca was considered as a huge favourite. Alekhine had previously never beaten him. Capa had also won the New York 1927 tournament before the match, 2.5 points ahead of challenger, beating him in their individual encounter in the process. Whole chess world was flashed by Capa’s genius and it would appear Cuban himself started believing he was invincible.

The match started on September 9, 1927, in Buenos Aires. The regulations were in accordion to London Rules: each player had 2.5 hours for 40 moves and the first player to win six games, draws not counting, was to be declared the winner. Although some sources have claimed Capablanca would keep his title in the event of the 5-5 score, Edward Winter claims such a proposition was never a part of the match agreement.

In any case, the match started with a shock for Capablanca. Already in the first game, he played terribly as White against the French defence and lost his first game against Alekhine. As a result, he would only play d4 on the first move during the remainder of the match. Since Alekhine also played only d4 and both players played only d5 in reply, the match would become a lengthy discussion on the Queen’s Gambit Declined theme.

Capa retaliated in the 3rd game and built upon his success in the 7th game. It would appear everything is back to „normal“, but then Alekhine created a fantastic double in the 11th and 12th game and took the lead. It would appear this pair of games made Capa realize that loss of a title is a legitimate option and the second half of the match was more tense, nervous and dramatic.

Thus, in the 20th game, the challenger missed an excellent winning chance. Nevertheless, in the 21st game, he completely destroyed Capa with the Black pieces and increased his lead to 4-2. Still, in the 22nd game, he failed to deliver the coup the grace and let Capa escape with a draw. It would appear this result encouraged Capa and gave him new lease of life.

It was Alekhine’s turn to suffer. First, he barely saved the 28th game with the help of a brilliant defence. Then he lost the 29th game after blundering heavily and somehow survived in the 31st game. Had Capa won that game, the result would have been 4-4 and the match would virtually start a new.

As it turned out, the 31st game was the decisive moment of the match. Alekhine retaliated in the 32 game and then „finished“ the job in the 34th game, which the champion played without any energy or hope whatsoever.

Thus, with the miraculous 6-3 result, Alekhine accomplished one of the greatest surprises in the history of chess and became the fourth World Champion.

In his book Garry Kasparov on My Great Predecessors, page 328, the greatest player ever gave his own opinion about Capablanca’s failure:

„On the whole, the reasons for the champion’s failure are clear: excessive self-confidence and, as a consequence, weak preparation, a habitual inclination to try and win with little expenditure of effort, without tension and the calculation of ‘dangerous’ variations, hence the tactical errors, and then, after encountering an incredibly resourceful opponent and a number of heavy defeats – shock, despair, loss of belief in himself…“

Sources:

Chesshistory.com: Capablanca vs Alekhine 1927

Chessgames: Capablanca – Alekhine, 1927

Chesspedia: Capablanca – Alekhine, 1927