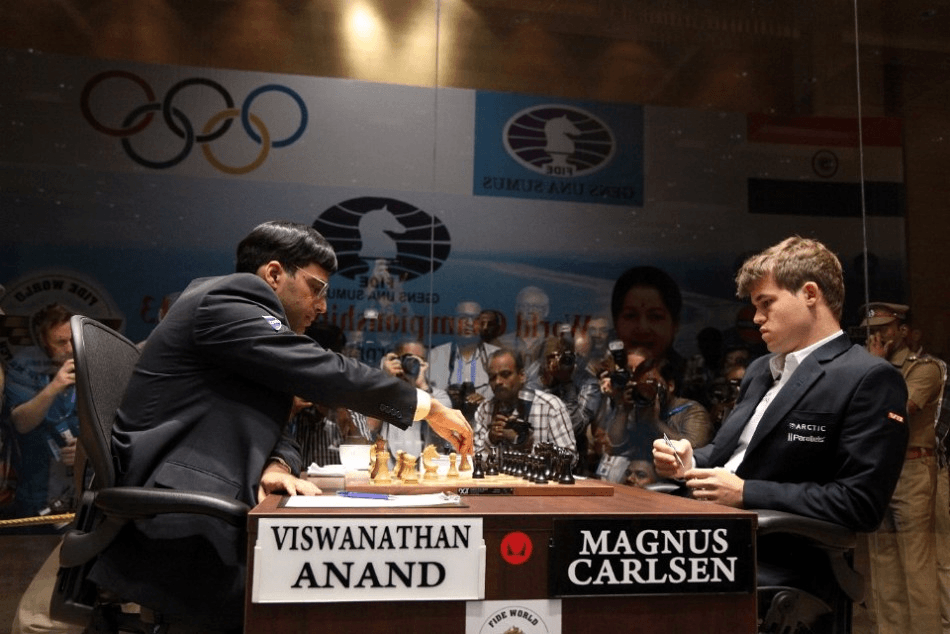

Since capturing the title of the World Champion in 2007, Viswanathan Anand has successfully defended his crown on three occasions. In the Anand – Kramnik, Anand – Topalov and Anand – Gelfand matches, he has mainly played against players of his own generation.

Therefore, his match against the new challenger, the Norwegian prodigy Magnus Carlsen in 2013 was awaited with great anticipation. Magnus has been a serious contender already in the previous World Championship Cycle. But back in the day, he took a surprising decision – he withdrew from the Candidates tournament, as a way of protesting against the knock-out format.

In 2013, though, the format of the Candidates tournament was changed to round-robin. This time Carlsen participated, after qualifying via average rating. Together with Peter Svidler, Alexander Grischuk and Vassily Ivanchuk (Chess World Cup 2011 qualifiers), Levon Aronian and Vladimir Kramnik (other two rating qualifiers), Teimour Radjabov (Organizer Wild Card) and Boris Gelfand (runner-up of the previous World Championship), he gathered in London in March to determine Vishy’s challenger.

Carlsen and Aronian were considered as the main pre-tournament favorites. And indeed, after the first half of the tournament, they were tied for first, one and a half point ahead of Kramnik and Svidler. But then, an incredible turn of events started unfolding.

First of all, Levon Aronian lost three games in the second half. On the other hand, Kramnik started berserking and won four games. Carlsen managed to maintain his lead until round 12, when he lost to Ivanchuk, allowing Kramnik to overtake him by half a point.

In round 13, Carlsen ground down Radjabov in an epic endgame, while Kramnik drew with Gelfand. Before the last round, the players were tied, but Carlsen had a superior tie-break (more wins). Carlsen was playing White, but incredibly enough – lost against Svidler. Alas, since Kramnik didn’t think such a result is very probably, he played for the win with the Black pieces and went for a risky Pirc. His opponent, Ivanchuk, gained a firm advantage and went on to outplay him from the beginning of the end.

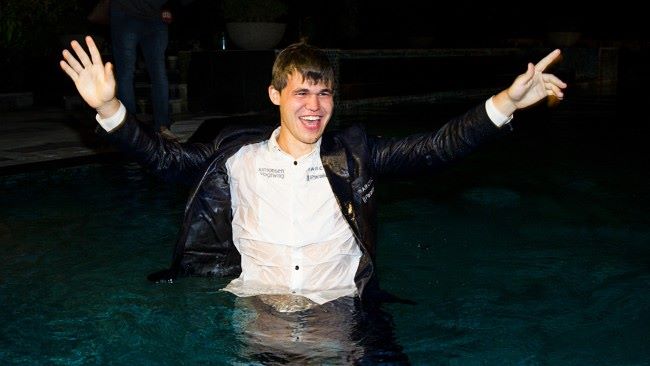

This dramatic turn of events allowed Carlsen to win the tournament and challenge Anand. The match took place on Anand’s home soil, in the Indian city of Chennai, from 8th to 22nd November 2013.

Although Anand had a huge support of the home crowd, Carlsen has been regarded as a huge favorite. The Norwegian has been the youngest player ever to break the 2800 rating barrier, has been the World number one since 2010 and has been dominating tournament play, while Anand hasn’t won a super-tournament for quite some time.

Most of the forecasts ignored their head-to-head score, which was the only thing standing heavily in Anand’s favor (6-3 in terms of decisive games). Anand won many games long before the match when Carlsen was much younger and still under development.

The match itself confirmed the pre-match forecasts. After the first four games, in which Carlsen played cautiously with White (1.Nf3) and solidly with Black (the infamous Berlin Defence), he managed to open his account after outplaying Anand in typical Carlsen style in a Queen Gambit endgame.

Carlsen immediately built-up on his success in the sixth game, where he outplayed Anand in yet another endgame. This time, Anand avoided the Berlin endgame in favor of 4 d3, but didn’t gain any substantial advantage. In a resulting rook endgame, Carlsen skillfully built pressure, sacrificed his queenside pawns for activity, and exploited Anand’s error by creating a strong passed f-pawn that ultimately decided the game.

This win put Carlsen firmly in control. Anand, not giving up completely, switched to d4 and chose the very sharp 4 f3 system in the 9th game, obtaining precisely what he wanted; a sharp position with mutual chances.

However, Carlsen didn’t falter, defended brilliantly, and went on to win that game as well after Anand blundered in a very complicated position.

After a quick draw in game ten, Carlsen won the match ahead of schedule and became the World Champion. The chess public saw this as a logical outcome of his dominance established over the preceding couple of years.