Disclaimer 1: The following article contains several affiliate links to Amazon.com, meaning that if you go to Amazon and buy the recommended product (or some other product in an allotted period of time), the author of these lines will get a commission % from the purchase

Disclaimer 2: The following article is an excerpt from my article titled Best Chess Books 2022 in which I reviewed 20 chess books

Jacob Aagard: Attacking Manual 1: Basic Principles

If anyone out there is not familiar with the name of GM Jacob Aagaard, he is a Scottish Grandmaster of Danish origin with a peak FIDE rating of 2542. However, rather than for his playing achievements 1 he is much better known nowadays due to his work as a chess trainer, chess writer, book editor and publisher.

He is one of the main coaches of the American superstar and former US Champion GM Sam Shankland 2, the founder of the platform Killer Chess Training and also the founder of the Quality Chess book publisher (who published the aforementioned book Think Like A Super GM, among a myriad of other high-quality titles).

Aagaard is also a very prolific chess writer, who has written more than 20 books since 1998. However, it is not only about quantity – his books are well-known and highly regarded due to their very high quality. Almost any stronger chess player will be familiar with at least one of Aagard’s titles and it is not really surprising a number of his publications have received multiple awards.

Aagaard has written books on different topics. But since I was focusing on improving my attacking play in 2022, I decided to start with the first part of the two-series book devoted to this very topic, titled Attacking Manual 1: Basic Principles.

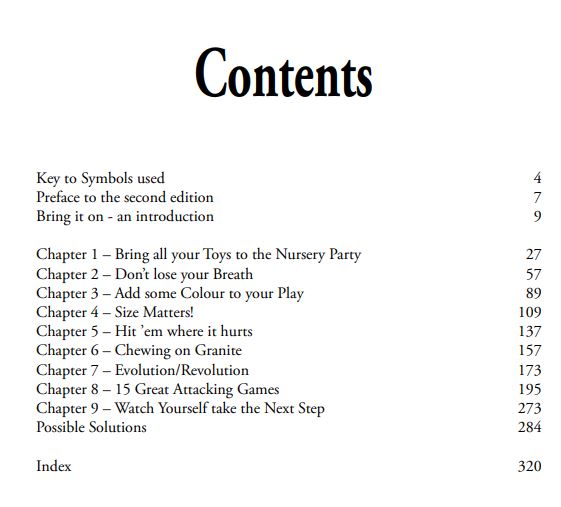

As the title suggests, the book focuses on what Aagaard considers to be the basic principles of attacking play, as follows:

- Chapter 1: Bring All Your Toys to the Nursery Party – a chapter about including every single piece into the attack

- Chapter 2: Don’t Lose Your Breath – a chapter about momentum and maintaining it throughout the attack

- Chapter 3: Add some Colour To Your Play – a chapter about attacking the weakened colour complexes around the king

- Chapter 4: Size Matters – a chapter about sacrificing the material in order to keep the attack going

- Chapter 5: Hit ’em where it hurts – a chapter about attacking your opponent on their weakest point/square

- Chapter 6: Chewing on granite – a chapter about attacking your opponent on their strongest point/square 3

- Chapter 7: Evolution/Revolution – a novel concept I have never stumbled upon prior to reading this book. Evolution is, very simplistically, a concept of building up the position and revolution is the concept of changing the nature of the position. 4

In the final two chapters, the author provides us with fifteen great attacking games and with a set of 50 positions we can solve as exercises, or use as starting positions for training games.

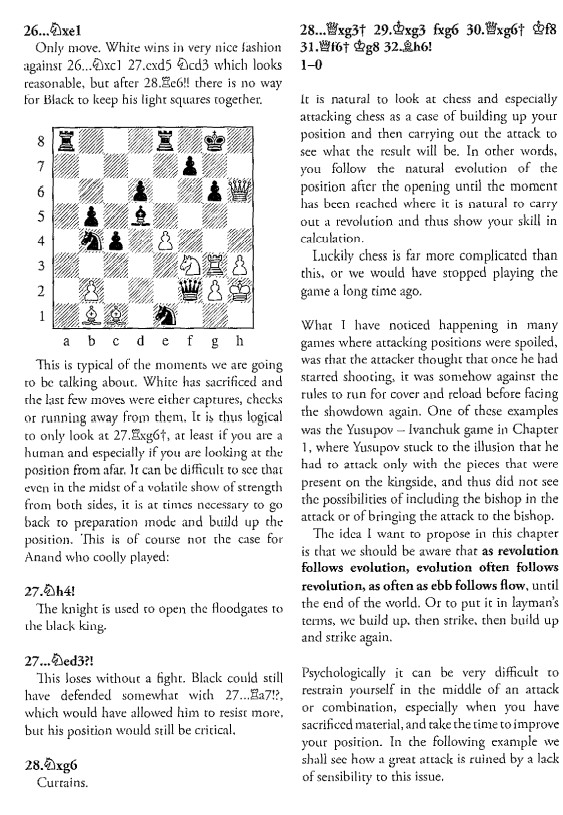

Every chapter consists of a series of deeply annotated and analyzed games. And when I say deeply – I really mean it. Attacking Manual – just like many other Aagaard works – is one of the most deeply annotated books I have ever seen. The number of textual explanations are quite astounding, irrespective of whether we are talking about explanations of concepts at the beginning of each chapter, annotations to the games themselves, or chunks of texts between the games in each chapter, which often talk deeply about the concept studied, while often digressing into other chess-related topics.

One additional aspect I really like about this book is simply – how it looks. As mentioned earlier, one of the things I really like about Quality Chess books is their outline, editing, and structure. I am simply very much a fan of how their books look visually – from font, text outline, diagram size, diagram placement, etc. In general, I do think their books are very pleasurable and enjoyable to read.

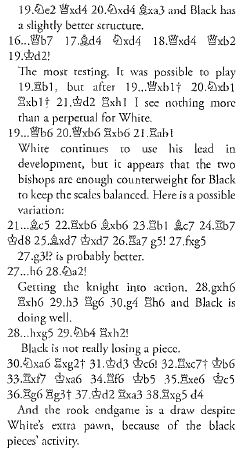

So much about the good sides. Alas, one of the big issues I have with this book is its sheer complexity. As mentioned earlier, the level of its depth is astounding, both in terms of the textual explanations and in terms of computer analysis provided. However, while it is definitely desirable in terms of the former, I am not 100% sure if it is desirable when we are talking about the latter. There are quite a few places within the book where the analysis of the subvariations goes on for 15+ moves long, for example on page 211:

I understand how it is very necessary to check everything thoroughly with the modern engines when you are a chess book author in the 21st century, but I am not 100% sure whether it is beneficial to have a major chunk of that analysis presented in a book – especially a book with the title „Manual” with the clear educational/pedagogical purpose.

I understand that such an approach is quite characteristic of all of Aagaard’s books 5 and that it was also endorsed by another great trainer Mark Dvoretsky, but I have personally never enjoyed having a long-computer analysis presented in books and usually don’t bother checking it in greater detail anyway.

The other way in which the complexity manifests itself is the material itself, which is very complex and difficult in itself. Even though the concepts themselves are explained extremely clearly and are simple to grasp, the games provided are definitely NOT. The material is definitely not aimed at lower-rated players and even I have a feeling a lot of it went way above my head.

Of course, in a world constantly pushing for oversimplification and where people are more and more seeking to have everything spoonfed to them, it is refreshing to have a school of thought that insists that the most reliable path toward chess improvement is deep thinking and immersing yourself in the difficult material. 6

However, it can be very tricky to balance between making things too difficult and too easy and I do feel that Aagaard sometimes errs on the side of making things too difficult. 7

Thus, while I do respect the enormous effort that goes into Aagaard’s books and do genuinely think they are high-quality and excellent for higher-rated players, I definitely wouldn’t recommend them to anyone rated, say, below 2000 FIDE.

- Which are not to be dismissed, given that he, for example, became the Scottish National Champion in 2012

- Among others

- As you can notice, attacking play is not straightforward given that this is directly in contradiction with the previous chapter. However, in some cases, attacking the weakest point is not possible (or there is not one), which only leaves us with the option of attacking at the strongest one to keep the attack going.

- As you can see, this is somewhat complementary with the rest of the chapters, given that bringing all the pieces into the attack can be regarded as evolution in itself, but in the given chapter a bigger emphasis is put on this sudden switch from building up the attack to actually executing it

- One could even argue it is more pronounced in some other works, say, in the Grandmaster Preparation series

- I myself believe in that approach and have become a member of Aagaard’s Killer Chess Training and have been solving their weekly Killer Chess Homework for a few months now. And even though it is extremely difficult for someone of my level, I do put in the effort, manage to find it enjoyable, and am also starting to see some tangible improvements. Although it can be discussed whether constantly working on a difficult material might make you lose confidence/motivation. So far it hasn’t been the case with me, but whether all the work will eventually lead to an increase of playing strength remains to be seen. I do believe it will.

- This is not only my opinion – after years of immersion in the chess world, I have noticed similar sentiment toward Aagaard/Dvoretsky’s books expressed by a number of average club players. Furthermore, in episode number 26 of the Chicken Chess Podcast, GM Jan Gustafsson expressed similar doubts, by claiming that he doesn’t see the point in solving overly difficult exercises, as he felt they often don’t have as much relevance for actual practical play.