THE MATCH OF THE CENTURY

Ever since he qualified for the 1959 Candidates tournament at the age of 15, everybody realized there is something special about Robert James Fischer. By devouring chess books on a daily basis, Fischer single-handedly developed into the youngest grandmaster ever (at a time) and a world-class player. Already back then everybody “knew” it is only a matter of time until he becomes a World Champion.

However, due to his psychological instability and character traits, it would take him almost a decade to actually qualify for the World Championship match. After the controversial end to the 1962 Candidates Tournament, Fischer refused to participate in the 1964-1966 cycle, even though FIDE fulfilled his demand and abolished Candidate Tournament in favour of knockout matches. Then he also withdrew from the 1967 Sousse Interzonal. Only in the 1970-1972 cycle did he compete in the Candidates and break through to the World Championship final. And he did so in a breathtaking and spectacular manner.

However, as has become customary with Fischer things couldn’t unfold without some controversy. As a result of a lengthy dispute with Ed Edmonson, Executive Director of the US Chess Federation regarding the tournament format of the US Chess Championship, Fischer refused to participate in the 1969 National Championship, which was also the Zonal tournament for the next World Championship Cycle. The three qualifying places were won by Reshevsky, Addison and Benko. After some convincing, Benko decided to give his place to Fischer, as everyone was aware of Bobby’s strength at a time. FIDE didn’t object to this state of affairs, and Fischer was allowed to play in the Interzonal Tournament.

The Interzonal tournament held in Mallorca in 1970 marked the start of the legend. Although Fischer was leading the whole tournament, after 17 rounds he was just half a point ahead of Geller. But the 17th round turned out to be the start of the most amazing streaks in the chess history. After winning his concluding 7 games, Fischer won the tournament by a 3.5 point margin and qualified for the Candidates matches.

In the Candidates matches, miracles started to happen. In the quarterfinal, Fischer was paired against Mark Taimanov, a Soviet Chess Grandmaster who was also a classical pianist. In view of Fischer’s dominant performance at the Interzonal tournament, and his halo of invincibility, everyone considered him as a clear favourite, except from…Mark Taimanov himself. He dismissed Fischer are a “mere computer” and believed his own strength. Moreover, Mikhail Botvinnik agreed to guide Taimanov in this match and even put together a dossier about him and his games.

In any case, a tough struggle was expected, but instead, the match turned out to be a whitewash. After two hard-fought but deserved Fischer victories, the third game turned out to be the critical moment of the match. Many years later in an interview, Taimanov said:

„The third game proved to be the turning point of the match. After a pretty tactical sequence, I had managed to set my opponent serious problems. In a position that I considered to be winning, I could not find a way to break through his defences. For every promising idea, I found an answer for Fischer, I engrossed myself in a very deep think which did not produce any positive result. Frustrated and exhausted, I avoided the critical line in the end and lost the thread of the game, which lead to my defeat eventually.“

After the third game, Taimanov crumbled psychologically. It was especially apparent in the 5th game, in which he reached an easily drawn position and then blundered a rook after adjournment. The final score was devastating: 6-0 in Fischer’s favour. However, even Fischer himself said such a score didn’t reflect the true balance of strength. Nevertheless, his victory was impressive. After the match, Taimanov was severely punished by the Soviet authorities:

„The sanctions from the Soviet government were severe. I was deprived of my civil rights, my salary was taken away from me [all Soviet grandmasters received from their government a substantial salary], I was prohibited from travelling abroad and censored in the press. It was unthinkable for the authorities that a Soviet grandmaster could lose in such a way to an American, without a political explanation. I, therefore, became the object of slander and was accused, among other things, of secretly reading books of Solzhenitsin.“

In the semifinal, Fischer faced Bent Larsen, an inexhaustible optimist and second strongest Western grandmaster. Once again Fischer was considered a slight favourite, but once again a very tight struggle was expected. Many thought the catastrophe suffered by Taimanov was something that happens once in a century.

Probably not even Fischer in his wildest dreams could have expected another perfect result. But after six games, the scoreboard displayed the unthinkable: 6-0 in Fischer’s favour. Similarly like Taimanov, Larsen was let down by his nerves and optimism. He wanted to win the game at all costs and lost his objectivity in the process. As he himself said:

„You think I couldn’t have made a draw against Fischer? I could have done that with my eyes closed. I wanted to win!“

His perfect victories against Taimanov and Larsen are to this day probably the best match performances in the history of chess. Together with his seven wins in the Interzonals and the win in the very first game of the final match against Petrosian, Fischer’s victory streak consisted of 20 consecutive victories in the games against the world-class opposition. It is without any doubt one of the most impressive individual streaks in the history. No one else has dominated his contemporaries before.

However, I would like to play the devil’s advocate here. I think Fischer’s streak should be acknowledged, but not overemphasized. As I have argued at length in a previous post, I think we shouldn’t jump to proclaim Fischer greatest of all times solely on the basis of these results. The circumstances of those matches and the character traits of Larsen and Taimanov should be taken into consideration. I don’t think Fischer would be able to make such a streak in 20 tournament games, or if his opponents were, say, Korchnoi or Geller.

As already mentioned, in the Candidates final, Fischer played against the former World Champion, Tigran Petrosian. Despite being struck by a novelty in the very first game, Fischer navigated his way through complications, took advantage of his opponent’s uncertain play and gained his 20th consecutive victory. People already evoked Taimanov and Larsen’s matches, but here a ‘miracle’ happened. Petrosian won the very next game with the White pieces and ended Fischer’s run. After this, three draws followed, in which Petrosian was the one holding the initiative (especially in the third game, in which he allowed an unfortunate repetition of the moves).

However, starting from the game six, Petrosian ran out of steam and started playing much less strongly. Fischer, having gained the psychological edge, became unstoppable and ended the match with the series of four consecutive wins. Botvinnik’s comment on the match basically tells it all:

„When Petrosian played like Petrosian, Fischer played like an ordinary grandmaster. When Petrosian started making mistakes, Fischer was transformed into a genius.“

Finally, after so many years, Fischer has reached the World Championship final. Despite having to face an opponent he had never beaten before (Spassky had a +3=0-2 score against him), he was considered as a huge favourite. His stunning run in the Candidates has increased his rating to the record height of 2785, a full 125 points(!) more than Spassky’s 2660.

Even before the match started, it was already jeopardized by Fischer’s behaviour. The choice of venue was already an issue. Fischer insisted on playing in Belgrade or on the American soil, dismissing a generous offer from Reykjavik (125 000 dollars). In the end, Max Euwe exerted his authority as the FIDE president and chose Rejkjavik, threatening to default the challenger if he didn’t show up. However, even then, Fischer didn’t sign any sort of official participation agreement. He kept demanding an increase in the prize fund, a percentage of the television rights and other customary demands, such as improvement of lightning and cushion seats.

It has to be said that throughout his life, Fischer was well known for having a list of demands in virtually every tournament in which he appeared. Fischer’s demands have improved the conditions and rights of chess players worldwide ever since. If it weren’t for him, who knows when would have chess organizers started considering players and the conditions in which the tournaments are held and not only their pocket. However, I agree with Kasparov’s assertion that Fischer more often than not used these demands as psychological weapons. Petrosian’s remark is worth noting:

„Long before the start of play Fischer achieves all those privileges and conditions that he wants. At the same time, his opponent does not obtain and cannot obtain the same. It is hard for a player, when he knows beforehand that he is playing in that town or that venue where his opponent wants to play, that the lighting has been arranged in the order of his opponent, that one player is receiving an additional appearance fee and the other is not[…]All this creates in Fischer’s opponent a definite complex[…]“

Larsen wrote something similar:

„Many consider Fischer to be a ‘big child’, and to some extent, that is indeed so. However, it should not be forgotten that children are sometimes very cunning and contrive very cleverly to impose their will on others…“

(Quotes taken from Garry Kasparov on My Great Predecessors Part IV, pages 407 and 437)

Anyhow, mere days before the match start, Fischer still wasn’t present in Reykjavik. He even missed the opening ceremony of the match and kept demanding an increase of the prize fund. Only after English sponsor Jim Slater doubled the prize fund and wrote a personal letter to Fischer in which he said ‘Now come out and play, chicken!’ and Henry Kissinger made a famous, ‘We want you to fight for America!’ phone call, until Fischer finally appeared.

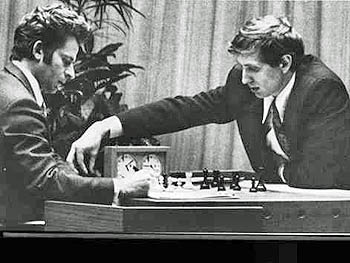

The match generated unprecedented media interest. It has to be remembered it was played at the height of the Cold War. Many people perceived Fischer as a lone genius on a task to dethrone the whole Soviet system. An exceptional and gifted individual like Fischer was a hero American public needed. It is not surprising that despite being an ‘ordinary’ World Championship Match, due to its significance it was labelled ‘The Match of the Century’ (Kasparov himself christened it as ‘Battle of Gods’).

Finally, on 11th July 1972, the match started. Already in the very first game, miracles started to happen. In a dead drawn endgame, Fischer captured a poisoned pawn and after multiple adventures went on to lose. Afterwards, he claimed the presence of TV cameras disturbed him and demanded their removal from the playing hall. After failing to appear for the second game, he defaulted. Spassky gained the 2-0 lead and the fate of the match once again hung by a thread.

At this particular moment, Spassky played a noble move (or committed a fatal blunder, depending on how you look at it). He agreed to play the third game behind the curtains, in a closed room, away from the TV cameras. There, Fischer beat him for the first time in his life and gained the necessary confidence and Fischer hurricane had started. By switching from e4 to d4 from the first time in his life in game 6 (a possibility mentioned by Korchnoi before the match that wasn’t taken very seriously by Spassky) he completely threw Spassky off the balance. After 10 games, the score was already 5-2 in Fischer’s favour and although the second half of the match was more peaceful, the outcome was never in question. After 21 games, Fischer won the match with the 12.5-8.5 result and became the 11th World Champion.

Sources:

Chessgames: Palma De Mallorca Interzonal 1970

Chessgames: Fischer- Taimanov Candidates Match

Chessgames: Fischer-Spassky, 1972

Chesschamps: US Chess Championship 1969

Wikipedia: World Chess Championship 1972

Chessbase: Interview with Mark Taimanov

Chesshistory: Spassky – Fischer

Garry Kasparov on My Great Predecessors Part IV

The most chaotic chess event of the 20th century. Spassky, who had troubles with the soviet federation and selecting his own team, did not play to his usual high standards. Stronger and more steady in the second half of the match, but with a 3 points deficit, it was too late. He lost the match largely for psychological reasons, in my opinion.