INTRODUCTION

Throughout history, chess was revolutionized several times.

In the late 19th century, the first World Champion Wilhelm Steinitz provoked his opponents to attack him vigorously and laid the foundations of positional chess.

In the middle of the 20th century, the sixth World Champion Mikhail Botvinnik started devoting an enormous amount of time to physical and chess preparation before the tournaments and matches, announcing the era of strict chess professionalism.

In the 1970s, largely under the influence of eleventh World Champion Robert James Fischer, the opening theory went through massive changes. New opening systems such as the Hedgehog were introduced and new ideas were discovered in ancient opening systems, demonstrating the inexhaustible nature of chess.

Nothing else, however, has revolutionized chess so much as the appearance of computer chess engines. Nowadays, even the biggest beginners are familiar with the terms „Stockfish“ and „Rybka“ (especially when they are shouting their names in online chats while kibitzing the games of top chess players). Even a chess computer on your mobile phone is stronger than a grandmaster nowadays. It is not surprising players have started using them as a tool and learning from them.

Even though we all embrace computer chess engines as something normal and use them on a daily basis, most of us aren’t familiar with the challenges and problems previous generations had to face in order to create one. Who devised the first computer chess engine? How long did it take for computers to become stronger than humans? What is the difference between classical computer chess engines and Google’s Alpha Zero?

In this article, we will answer these questions and take a closer look at the history of computer chess engines.

THE 18TH CENTURY: THE TURK

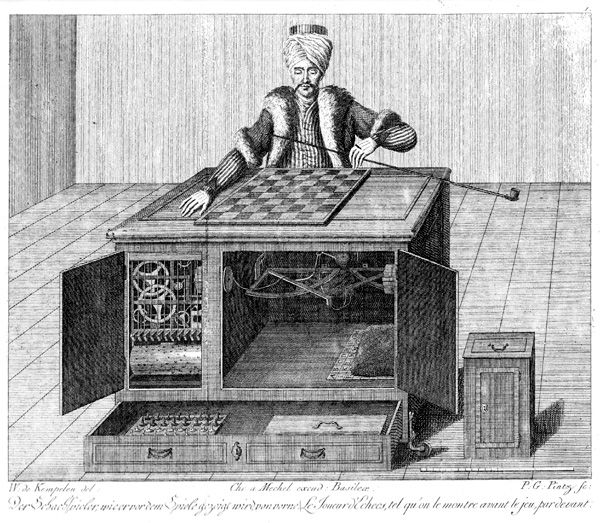

In 1769, French illusionist Francois Pelletier was performing an act in front of Maria Theresa of Austria, at the Schönbrunn Palace in Vienna. Among the onlookers was Hungarian inventor and author Wolfgang von Kempelen. Inspired by Pelletier’s performance, Kempelen immediately started building the invention which would later become one of the most notorious hoaxes in the entire history.

Next year, in 1770, at the exact same place, Kempelen exhibited the Turk – the first chess-playing automaton in history. Its complicated construction consisted of several compartments with various operational mechanisms. It incorporated a life-sized model of a human, dressed in traditional oriental clothes (hence its name).

Turk was capable of playing chess on its own and beating human opponents. It was even able to recognize illegal moves and force its opponents to take them back. In one exhibition, it even solved the difficult knight-tour-around-the-board puzzle.

There was just one problem. It was all fake. The Turk was not the one making all the moves. A human hidden inside it was.

You see, during the construction, Kempelen envisioned several hidden compartments, big enough to fit an adult. He even made sliding hallways, through which a person was able to move from one compartment to another. It was important to preserve the illusion – before each exhibition, Kempelen would invite the audience to examine the automaton, during which the operator of the machine would remain hidden.

And it worked? Kempelen toured Europe exhibiting his invention until his 1804. After his death, the machine changed several owners and continued playing chess until 1854, when a fire in Philadelphia sealed its fate. It is amazing no one realized the fraud during the Turk’s lifetime.

Thus, the first computer chess „engine“ was a major commercial success.

However, if we disregard several similar automatons, the development of chess engines was stalled during the next 100 years. The real breakthrough happened only in the late 1940s and early 1950s. And just like with many other technological advances, a major historical event fulfilled the role of the catalyst.

THE 1950s: THE BEGINNING OF AN ERA

During World War II, Axis and Allies leadership spent a lot of time hiring top scientists and gathering them into teams. The purpose was clear – winning the war. Greatest minds of the 20th century devoted their wartime years to developing technology and weapons that will help overpower the enemy. The science was in service of the war industry.

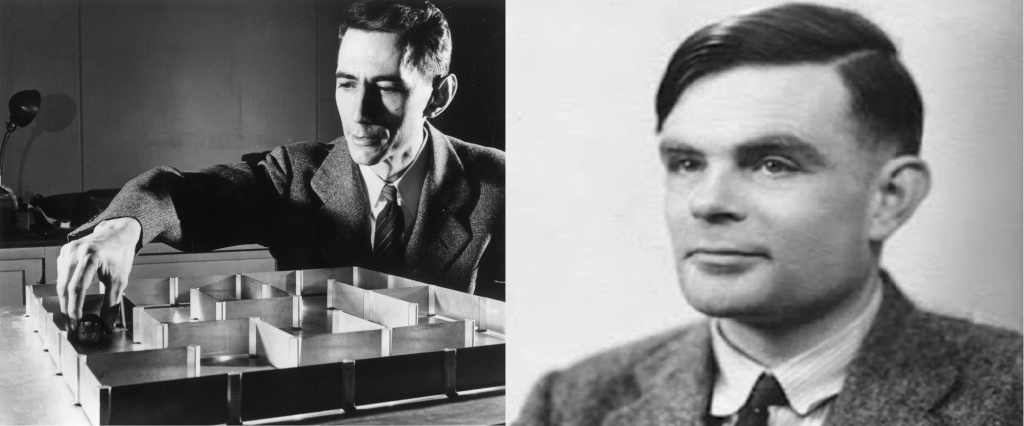

In spite of that, the war led to a startling amount of breakthroughs. Scientists laid a foundation for a number of new fields. In the context of this article, computer science is of particular interest. Two famous names played the crucial role in its development – Claude Shannon and Alan Turing.

Shannon is widely recognized as the father of the modern information theory, while Turing is the father of the modern computer (Turing’s machine!). Their contributions to the field of computer science are well known. What is perhaps lesser known, is that Shannon and Turing are also fathers of chess computer engines.

After finishing their PhDs on the eve of the war, Shannon and Turing both started working on cryptanalysis, in USA and UK, respectively. They closely followed each other’s work and even met in person back in 1943, during Turing’s two-month stay at Bell’s Lab in New York, where Shannon was working. After the war ended, they both took an increased interest in programming a chess computer.

(Main source describing the relationship between Shannon and Turing: Life In Code And Digits – When Shannon Met Turing)

In 1949, Shannon published an iconic paper titled “Programming a Computer For Playing Chess”, in which he described an algorithm for the chess-playing machine. Simultaneously, Turing was developing his own chess playing program. His work on “Turbochamp” started back in 1948 and finished in 1950.

It is noteworthy to mention Turing programmed Turbochamp on paper, without access to an actual computer. He tried testing it on Ferranti Mark I – the first commercially available computer – and failed. In the end, he tested it manually (!) in a friendly chess game in 1951.

(51 years later, none other than Garry Kasparov tested “Turbochamp”. The program didn’t stand a chance, but the greatest players of all times recognized how tremendous Turing’s achievement was – source: Alan Turing Created A Chess Computer).

It is not yet certain whether Shannon and Turing worked independently or were inspired by each other – the content of their conversations in 1943 is not known. However, even if they didn’t collaborate, their contributions were immense. Subsequent generations of computer chess developers all “stood on the shoulders” of these two giants.

In 1951, Turing’s colleague Dietrich Prinz managed to implement the algorithm on Ferranti Mark I and created a program capable of solving mate in two. In 1956, a team of scientists led by Stan Ulam (one of the inventors of the h-bomb)created a program capable of playing chess on a 6×6 board. And finally, in 1957, IBM engineer Alex Bernstein created the first automated program fully capable of playing a complete game of chess.

The era of computer chess has officially begun.

THE 1960s AND 1970s: SMALL STEP OR A GIANT LEAP?

The first computer chess engines were rather weak and primitive. During the 1960s and the 1970s, however, their strength increased rapidly. Two major factors contributed to this qualitative leap:

- Improved and more sophisticated algorithms

In the 1960s and 1970s, algorithms for the computer chess engines were significantly improved. The foundation was set by the genius of John Von Neumann, who developed the MiniMax algorithm, perfectly suited for the game of chess (it minimizes the score of one player while maximizing the score of another). In the decades that followed, MiniMax search was improved with advanced heuristic techniques and “iterative deepening”, which gradually increased the depth of the search by MiniMax.

- Improved and faster hardware

The greatest restriction for Turing and other pioneers was computing power. In the 1960s and 1970s, however, hardware speed increased exponentially – according to Moore’s law, the computing power doubled every two years. It allowed the implementation of advanced algorithms – the search time for MiniMax was significantly decreased.

It was not only the matter of raw computing power, though. In the 1960s and 1970s, computer chess gained prominence. The first all-computer chess championship was staged in 1970 in New York. Shortly afterward, in 1974, first World Chess Computer Chess Championship was staged in Stockholm. The appearance of the “scene” inevitably led to the foundation of specialized companies which started developing customized chess playing software and hardware. Which allowed computer chess engines to get even better.

How good “get better” was? How good were computer chess engines compared to humans at a time? Experience showed – good enough to beat an amateur, not good enough to compete with a master.

For instance, in 1967, MacHack VI became the first computer chess engine to beat a human opponent. It’s playing strength revolved around 1300 USCF rating. But already in 1976, a significant leap happened – chess computer engine Chess 4.5 won the Class B Section of the Paul Mason tournament in Northern California. In 1977 it also won Minnesota Open with the performance rating of 2271 and beat a Class A player Stenberg – rated 1969.

However, the computers weren’t on equal terms with stronger humans. In 1968, International Master David Levy bet 3000$ he would be able to beat any chess computer engine in the next 10 years. In 1977, he won his bet in a match against chess computer engine KAISSA. He also beat the newer version of MacHack in 1978.

Therefore, at the end of the 1970s, could compete against humans, but couldn’t play on a master level.

But then the 1980s arrived.

THE 1980s: CHALLENGE TO HUMANITY

By the start of the 1980s, computer chess engine programming has become a lucrative business. Personal computers have become widespread in households. The interest in customized and specialized software – including computer chess engines – exploded. In 1982 alone, computer chess companies topped 100 million in sales.

It is not surprising, thus, that computer chess engines continued improving. In 1980, their programming became a serious competition. Edward Fredkin, professor of computer science at Carnegie Mellon University, introduced the Fredkin Prize. He offered monetary prizes for various achievements in the world of computer chess programming (5000$ for the first engine to reach Master level, 10000$ for the first engine to reach Grandmaster level, 100000$ for the first engine to beat the World Champion).

The race was on. The number and strength of computer chess engines continued increasing.

Fredkin’s colleague from Carnegie Mellon University led the way. The most notable project and the spearhead of an entire generation is Deep Thought – the first chess computer engine which reached Grandmaster Level. In 1988, it shared the first place with Grandmaster Tony Miles in US Open Championship. In 1989, it easily beat International Master David Levy four games to zero.

The downfall of humanity seemed inevitable. In the search for its Champion, it turned to the reigning World Champion and arguably the greatest player of all times – Garry Kasparov. First, in an iconic simultaneous exhibition in Hamburg in 1985, he played against 32 (!) strongest chess engines – and beat all of them (!!). Then, in 1989, he faced Deep Thought in a two-game match, which he also won.

(Source: Kasparov And Thirty Years Of Computer Chess)

Therefore, in his encounters with engines in the 1980s, Garry became the “chosen one”.

Alas, in the 1990s, he too would fall.

1990 – 1997: ENGINES TAKE OVER

Thus, in 1989, humanity won the battle, but not yet the war. In the 1990s, many more clashes between humans and computer chess engines were held. Top chess engines even competed in elite chess tournaments – with mixed success. Several “human vs machine” matches were organized, but none of them became famous as the match in which the engine defeated the World Champion in 1997.

In 1989, researchers involved in the Deep Thought project were hired by IBM. They started developing a more powerful version of the engine.

The name of the project was Deep Blue. In 1996, only 7 years after the Kasparov – Deep Thought match, round two of „man vs. machine“ was held: the first Kasparov – Deep Blue match. In the very first game, Deep Blue shocked Kasparov and became the first chess computer engine to beat a World Champion in a classical game. However, Garry composed himself and won the match with the result 4-2, prolonging the inevitable once again.

The failure didn’t dishearten Deep Blue programmers. During the next year, they continued to improve the engine’s strength. They even hired Grandmaster Joel Benjamin as a consultant to help them build the opening book. After thorough preparation, they challenged Kasparov to a rematch again – and as they say – the rest is history.

In the celebrated match, Kasparov won the first game. But the engine’s counterintuitive 44th move confused him. It shook his confidence and he missed serious drawing chances in the 2nd game. Then Deep Blue crushed him in 6th game with a knight sacrifice early in the opening. This sealed Kasparov’s fate and earned Deep Blue team the Fredkin Prize.

(Source: Deep Blue Inventors Win Fredkin Prize)

After the match, he claimed IBM cheated and that a human was actually making the moves (Joel Benjamin). Other sources speculated a bug in Deep Blue’s code brought him victory.

(Source: Did Deep Blue Beat Kasparov Because Of A Glitch?)

In any case, 1997 symbolically marked the end of human domination over the chess computer engines.

However, humans didn’t yet resign.

1997-2006: HUMANITY’S LAST STAND

After Deep Blue’s victory, everyone expected the gap between the humans and machines to widen further. However, over the next six years, until roughly 2003, humanity made its last stand.

For instance, in 2000, computer chess engine Deep Junior participated in the Dortmund Elite Supertournament – and scored just 50%. In 2002, new World Champion Vladimir Kramnik drew his match against computer chess engine Deep Fritz (despite a catastrophic mate-in-one blunder). In 2003, Garry Kasparov drew two matches against Deep Junior 7 and X3d Fritz.

Alas, this small ray of hope was quickly destroyed by computer chess engine Hydra. In 2004, it beat GMs Evgeny Vladimirov (3-1) and Ruslan Ponomariov (2-0). Then, in 2005, it destroyed Michael Adams, a member of the world top 10, with a devastating score: 5.5-0.5.

And in 2006, Deep Fritz drove the final nail in the coffin of humanity by beating the World Champion Vladimir Kramnik 4-2.

2006-2017: THE GOLDEN ERA OF COMPUTER CHESS ENGINES

The 2006-2017 decade is the golden era of the computer chess engines.

On an everyday basis, computer chess engines infiltrated all areas of chess – from broadcasting and analyzing to playing. They became an integral tool for any chess tournament player. They raised a generation of strong youngsters – the so-called computer generation. When smartphones appeared, their Android and iOS versions were immediately developed, to the horror of any tournament anti-cheating committee.

World Chess Computer Championship continued growing. Due to the prestige and money involved, some controversies ensued. The most infamous case is the disqualification of the computer chess engine Rybka, the consecutive winner of the four editions between 2007-2010, due to code plagiarization.

(Source: Rybka, The World’s Best Chess Engine, Outlawed and Disqualified)

Apart from the World Chess Championship, a new competition was introduced in 2010 – Top Chess Engines Competition. In contrast to the WCC, TCEC features longer games played using high-end hardware, which leads to a higher quality of chess.

The human-machine matches proved the gap is widening. Over the decade, a number of handicap matches were held, in which engines gave various odds to strong grandmasters. The results were depressing for humanity. For instance, in 2014, computer chess engine Stockfish defeated GM Daniel Naroditsky who used the assistance of an early version of Rybka. In 2015, computer chess engine Komodo played 6 odds games against Sergei Movsesian, a former top 10 member and crushed him easily. And in 2016, Hikaru Nakamura, a current member of world top 10, feel down to Komodo as well.

(Sources: Man Versus Machine Historical Archive and Komodo Beats Nakamura In Final Battle)

In any case, during the 2006-2017 period, classical computer chess engines dominated. Until the end of 2017, nothing revolutionary happened. Their strength changed consistently, but slowly. Everything seemed familiar and nobody expected any radical changes, any major breakthroughs.

Then AlphaZero happened.

2017-ONWARD: A NEW REVOLUTION?

On 5th December 2017, a group of scientists from Google AI company Deep Mindshattered the chess world.

In the paper titled “Mastering Chess and Shogi by Self-Play with a General Reinforcement Learning Algorithm“, they described the development of a new chess engine, AlphaZero, based on a completely new approach. Instead of alpha-beta searching and linear approximation function for position evaluation used by traditional engines, AlphaZero uses non-linear approximation function based on a deep neural network and Monte Carlo Simulation. As a consequence, instead of brute-forcing through the analysis, AlphaZero is able to “self-learn” chess.

The team tested the strength of the new engine in a 100 game match against the strongest classical chess engine available at the moment – Stockfish 8. The result of the match was staggering – +28-0=72 in AlphaZero’s favor. But what was even more impressive was AlphaZero’s style of play – it was much more intuitive and human-like than the play of the traditional engines.

The reactions to the paper were mixed. Many chess players were amazed – the mighty Stockfish suffering such a defeat was indeed a miracle. But on the other hand, there was a lot of skepticism. A lot of criticism has been directed toward the playing environment of the match – Stockfish ran on inferior hardware and played without an opening book. One interesting article on Medium was very careful to label Alpha Zero a scientific breakthrough in AI.

However, on 7th December 2018, another paper was published by the Deep Mind team, titled “A general reinforcement learning algorithm that masters chess, shogi, and Go through self-play“. In it, they presented the results of another match between Alpha Zero and Stockfish. Out of 1000 games, A0 won 155 games and lost only 6. Even though the older version of Stockfish was used, it is an impressive result.

Irrespective of whether skepticism is justified or not, Alpha Zero made a significant impact on the chess world. They forced everyone to start pondering about what is coming next. They might signify the start another revolution.

One thing is certain: with the entry of AI, computer chess engines will never be the same.

REFERENCES AND ADDITIONAL READING

The Best Schools: Brief History Of Computer Chess

Bill Wall: Early Chess Computers

HPC Wire: Deep Blue Inventors Win Fredkin Prize For Computer Chess

David Levy defeated Chess 4.7? As the main match of the bet, it was a best of 6 as I remember, the other 2 matches were best of 2. There are many other important gaps in the history of chess computers.

Humanity’s last stand? That sounds as if computers are aliens that came to Earth and started beating people at chess; when of course all computer advances are from human engineering….

Hi RM, the reason its worded like this has to do with the singularity idea that proves AI is smarter than humans have or will be.

I don’t see AlphaZero listed on any 2022 list of top chess engines. Seems like it just has some mythical status…