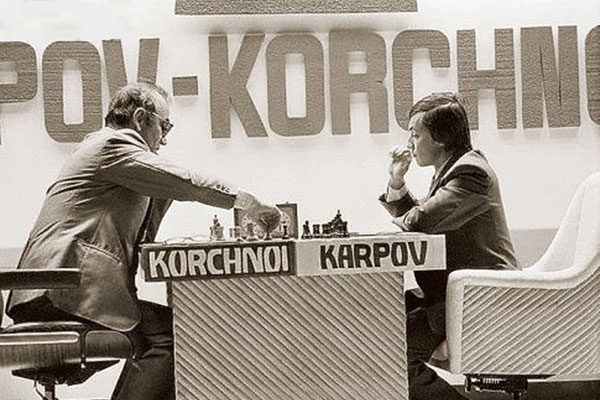

Starting from the early 60s, Viktor Korchnoi has always been one of the top Soviet Grandmasters. As a four times Soviet Champion and a regular participant in the Candidates tournament, he actively participated in the battle for the chess crown, yet he was always overshadowed by a fellow countryman. In the 60s, both Petrosian and Spassky proved to be stronger and in the 70s, young Anatoly Karpov. Their individual clash in the 1974 Candidates final was won narrowly by the younger player. As it later transpired, Fischer’s abdication meant that the winner of this match effectively became the World Champion.

However, the match was not only significant from the competitive point of view, but also from a historical perspective. You see, throughout the 60s, Viktor Korchnoi has always had the feeling he is being sidelined by the Soviet authorities in favour of other players. For instance, although he was the Soviet Champion in 1963 when the organizers of the Pitagoirsky Cup sent three invitations, only Keres and Petrosian were allowed to go. Throughout the 60s, he has always had the feeling someone is working against him. That someone else is the chosen one.

When young Karpov appeared on the horizon, a similar pattern repeated itself. He immediately became the favourite of both the public and the authorities. It is therefore not surprising that prior to their 1974 match, Petrosian made a statement in which he claimed his generation (including Korchnoi) was defeated by Fischer and can’t successfully battle against him. Therefore, they should focus on the development of the younger players…

Naturally, Korchnoi, who had just qualified for the Candidates final, was outraged. After his loss in the match, in an interview for the Yugoslav newspaper Politika, he said that: “He cannot say that a brilliant future awaits him [Karpov]”.

Such a statement was incentive Soviet authorities were just waiting for. They immediately banned him from playing in international tournaments and they reduced his grandmaster stipend by one third. When Keres and Nei invited him to play in the 1975 international tournament in Estonia, he wasn’t allowed to go and Keres and Nei were reprimanded for their behaviour.

Probably somewhere around then Korchnoi started seriously considering the way out – defection to another federation. After Karpov inherited the title of the World Champion, the iron hand of the authorities loosened its grip a bit – they wanted to prove that Karpov was a worthy champion and he needed to compete against the strongest opposition. Thus, in 1976, Korchnoi was allowed to play in the 1976 Amsterdam Tournament, at the end of which he asked Tony Miles to spell „political asylum“ for him. He then went to a nearby police station to defect.

Thus Korchnoi became the first Soviet grandmaster to defect to West. Moreover, the Cold War was not yet over and Leonid Brezhnev had risen to power. Korchnoi’s son and wife remained in the USSR. All these events set the stage for the most controversial match in the chess history, match filled with mutual accusations, drama and high political tensions. Just as in the Match of the Century, Soviet authorities very much feared that chess title would escape to the West. This time it was arguably even worse. This time, the ‘traitor’ was on the other side. But we are getting ahead of ourselves.

The 1976-1978 cycle started with the two separate Interzonal Tournaments, held in Manila and Biel in the summer of 1976. Mecking, Plugaevsky, Hort and Larsen, Petrosian and Portisch grabbed the 6 qualifying spots. They were joined by Fischer and Korchnoi to form the Candidates quarter-final pairings. When Fischer declined to participate, Spassky, as the losing semi-finalist of the previous edition, was granted the opportunity to play instead. In any case, after beating the trio of the Soviet- Grandmasters – his nemesis Petrosian, the great opening expert Lev Polugaevsky and Spassky himself, Korchnoi reached the World Championship final and qualified for the match against Karpov.

The match was played in Baguio City, Philippines. For the first time in the history, the World Championship Match was held on the Asian soil. How did it come to be? As Mark Weeks explains:

„How did it happen that the first match was played in Asia for the World Chess Championship?

The bidding process was straightforward. Five weeks after the candidates final match, sealed bids were to be delivered by interested parties. The players then had two weeks to choose three venues, after which FIDE President Euwe would announce the site.

Seven bids were received. Substantial offers were made by Graz, Hamburg, Baguio City, and Tilburg, while token offers were made by Lucerne, Paris, and Il Ciocco. Neither player wanted to choose the other player’s known preference. Karpov chose Hamburg, Baguio, Graz, while Korchnoi chose Graz, Baguio, Tilburg, Hamburg. Euwe chose the second site on each player’s list and announced in March that the match would take place in the Philippines.“

Match venue wasn’t the only novelty introduced. Match conditions were also changed. For the first time since the Alekhine – Capablanca match, the number of the games was unlimited. The first player to win six games draws not counting, would be declared the winner. Also, the rematch clause, abolished back in 1963 (before the Botvinnik – Petrosian match) was reintroduced.

As already mentioned, the match was played under dramatic political circumstances. It is not surprising there were numerous off-the-board intrigues (in my opinion, this match is the most controversial match in the history of chess, surpassing the infamous Kramnik – Topalov, 2006 Toiletgate in Elista by a small margin). Some of the notable off-the-board events were:

- Korchnoi insisting on bringing his own chair and Karpov demanding it is exhibited. A couple of days before the match, the chair was X-rayed in a nearby hospital.

- Korchnoi wearing sunglasses and Karpov complaining it deflected light in his eyes.

- A yoghurt being passed to Karpov during one of the games and Korchnoi claiming it contained some sort of prohibited substance.

- Korchnoi complaining about the infamous Dr. Zukhar, a parapsychologist and the member of the Karpov’s team. Korchnoi said Zukhar’s stare contained hypnotic powers. As we will see, the battle „for“ and „against“ Zukhar remained the main controversy throughout the whole match.

- Starting from the 18th game onwards, Korchnoi started bringing his own yogis, Dada and Didi, as a measure against Dr. Zukhar. These two members of the Ananda Darga movement supposedly helped Korchnoi meditate and relax before the games. The only problem was they were wanted for the murder of the Indian diplomat in the very same country the match was held.

The events happening on the board were no less dramatic. After the initial series of draws, Karpov breached Korchnoi’s Open Ruy Lopez in the 8th game. Korchnoi retaliated in the 11th game. But then in the 13th game, he outplayed the Champion with the White pieces, but then made a tragic blunder that lost the game. Karpov built upon his success after breaching the Open Ruy for the second time in the 14th game.

Then, in the 17th game, another shock followed. Korchnoi once again outplayed Karpov convincingly but was once again unable to find the most precise way of converting. On the move 39, in a drawn position, he made yet another blunder, overlooking a mating threat, and the score became 4-1 in Karpov’s favour.

(I have annotated that fatal game in a separate post dedicated to Korchnoi)

At this point, almost everyone expected a smooth end to the match for Karpov. But in the second half, miracles started to happen. First Korchnoi won the 17th game: 4-2. Then a long series of draws followed, demonstrating for the first time the absurdity of the unlimited match format. Then, in the 27th game, Karpov won once again and Korchnoi found himself in a desperate situation.

However, incredibly enough, in the next four games, Korchnoi managed to win three times and to level the scores. The crisis had reached its peak – the loss of the title became a reality. In this situation the Soviet authorities made a very important move – they managed to ban Korchnoi’s yogis from attending the 32nd game and they also made sure dr. Zukhar (who has been sitting in the back seats beforehand) sits in the very front row. It seems that crucial role in this coup de grace was played by one of Korchnoi’s seconds, Grandmaster Raymond Keene (see an excellent Kingpinchess article titled Backstabbing in Baguio for the more extensive elaboration).

In any case, in the 32nd game, Korchnoi played rather badly, mishandling the Black side of the Pirc defence and suffering quite a devastating loss. Thus, after 32 dramatic games, Karpov managed to endure the pressure and to remain the World Champion, while Korchnoi would have to wait for another three years for the next opportunity.

The controversy of the 1978 match did not end with the match as well. Many years later, Korchnoi claimed he very much feared for his life in the event of him becoming the World Champion. According to Kasparov, there were even rumours Soviet’s authorities already prepared plans for Korchnoi’s elimination:

“But what would have happened in the event of him losing? Ten years later, already in the era of perestroika and glasnost, Mikhail Tal, appearing on television, was to say with a smile: ‘ We could not imagine the consequences if an anti-Soviet player, not a Soviet, had become world champion[…] There, in Baguio, we were all afraid for you (Korchnoi) – if you had won the match, you could have been physically eliminated. Everything had been prepared for this…”

(Garry Kasparov On My Great Predecessors Part Five, page 340)

Sources:

Wikipedia: World Chess Championship 1978

Rappler: Karpov- Korchnoi Chess Championship

Chessgames: Karpov – Korchnoi, 1978

Kingpinchess: Backstabbing in Baguio

Viktor Korchnoi: Chess is my life