After his successful title defence against Korchnoi in 1981, it appeared Karpov would have no equal for a long time. The old generation was fading slowly, but surely, and it seemed that it would take a while for the new generation to grow, develop and challenge the formidable champion.

Alas, these forecasts were quickly overturned by a sensation from Baku which will become a synonym for chess many decades later – Garry Kasparov.

Born in Baku in 1963, Kasparov demonstrated his colossal chess talent already at the age of 13 by winning the USSR Junior Championship. His subsequent stratospheric rise to the world elite was marked with a number of groundbreaking achievements, such as:

- victory at the Baku Tournament in 1978 (while he was still unrated)

- victory at the World Junior Championship 1980

- tied first at the USSR Chess Championship 1980-1981

- victory against Korchnoi at the Lucerne Olympiad in 1982

- victory at the Bugojno chess tournament 1982

to name a few.

This period was crowned with the victory at the 1982 Interzonal Tournament in Moscow, which earned him a spot in the upcoming Candidates matches. At the age of 19, Garry became the youngest Candidate since Fischer.

After all these triumphs, Garry also became the second highest rated player in the world (according to the January 1983 rating list). It was clear to everyone that Karpov has gained a worthy challenger, but probably no one predicted the rivalry of the two K’s would last for more than a decade.

But we are getting ahead of ourselves.

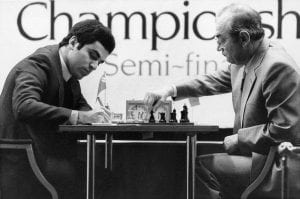

In the Candidates quarter-final, Kasparov was paired against Alexander Beliavsky, whom he beat with ease. In the semi-final, he was paired against Viktor Korchnoi. As has become customary with the affairs involving Korchnoi and the Soviet players, the involvement of authorities caused major controversy. Due to a series moves made off-the-board, Kasparov didn’t appear in Pasadena, California for the beginning of the match and was thus forfeited. Instead of accepting the win on default, Korchnoi insisted for the match to be rescheduled, which he would lose (despite the win in the very first game).

Many years later, Kasparov expressed his gratitude in a Chessbase interview following up Korchnoi’s death:

“Korchnoi had a direct impact on my life beyond his chess. We were scheduled to face each other in a 1983 Candidates match slated to take place in Los Angeles. A great deal of controversy and provocation by the international and Soviet sports authorities around which site would host the match led instead to my being forfeited. It is impossible to say what would have happened had anyone but Viktor Korchnoi been my opponent, but there is no doubt he did what he could to make sure our match was decided at the board, not the boardroom. Despite being 32 years my senior and an underdog in our match, winning without playing was unacceptable to Korchnoi. He was a man who enjoyed picking fights, not dodging them! And if he could antagonize the hated chess authorities of the USSR and Karpov in the process, more the better.

[…]

We met to negotiate at the 1983 Nikšić tournament, when organizers later held a blitz event in Herceg Novi that broke the blacklist by including Korchnoi. (The audience even applauded when he and I shook hands at the board.) I remember Korchnoi telling me that now that I was playing in the West, I had to get better shoes, that you could always tell a Soviet man by his shoes! After negotiations to reschedule our match in London succeeded, I wanted to thank Korchnoi but he was having none of it. This wasn’t a present to me; he was planning to beat me!“

In the Candidates final, Kasparov met an unexpected opponent. Former World Champion Vassily Smyslov, who was 63 (!!) at a time, qualified for the final after beating Robert Hübner with some luck (the outcome of the match was decided by the spin of the roulette wheel) and after a convincing victory against Zoltan Ribli. Alas, the elderly legend was no match for young Kasparov, who qualified for the match against Karpov with the convincing 8.5-4.5 victory.

The long-awaited match between Kasparov and Karpov started in September 1984. Just as in the two previous matches, the number of the games was unlimited – the first player to score six wins, draw not counting, would win the title.

Although everybody expected a tough and nail-biting match, the beginning of the match was a catastrophe for the challenger. After just nine games, he found himself in a desperate situation – the result was standing at 0-4 and champion was completely dominating. By Kasparov’s own admission, the main reason behind his failure was his inability to control his nerves.

However, just as everyone started expecting an abrupt finish to the match, Kasparov started making draws and, slowly, but steadily, gaining some ground. After a series of 17 draws between games 10-26, Karpov managed to score another victory in game 27. It would appear that this victory did him a disservice because he obviously relaxed assuming challenger’s final collapse is merely a matter of time.

Kasparov refused to give up and in the 32nd game, managed to score his first victory in the match. After this, another long series of 14 draws followed, after which something incredible happened – Kasparov won games 47 and 48. The score became 5-3. The memory of the match in the Baguio City (where Karpov blew a 5-2 lead only to close the match by the narrowest of margins) was still fresh. After six months of play, both players were on the verge of exhaustion. Also, the playing venue was required for other purposes which put the organizers in a difficult position.

In such a situation, FIDE President Florencio Campomanes took an unprecedented decision. On 8 February 1985, he announced the termination of the match. At the press conference announcing the termination, he cited the health of the two players as the main reason. A new match with the short-castling starting score (0-0. I know, I know, I will show myself out) and the limited number of games, was set to start in September 1985. To this day, this remains the only match in the history of the World Chess Championship that ended prematurely. Whose outcome was not determined over the board!

Even 33 years later, it is very hard to determine the circumstances which led to Campomanes’ decision and to judge objectively whom the decision favoured. It is beyond my expertise and knowledge to determine who was right and who was wrong – the matter has been investigated by a number of chess journalists and historians for quite some time. In my opinion, the most accurate and objective summary of the Termination incident is the report written by a notable Chess Historian Edward Winter on his website chesshistory.com. The short wrap up below is largely based on his two articles, Termination and Kasparov’s Child Of Change.

Both players claimed the decision was in favour of their opponent. Karpov claimed he was leading the match 5-3 and that the termination took his lead away. Kasparov, although he allegedly initially claimed his chances to win the match are 20-30%, later wrote he had every chance to win the match, due to his opponent’s exhaustion, to the fact he just won two games in a row and to the fact the quality of his play was increasing, and not decreasing. However, Kasparov’s accounts of the events are full of contradictions and inconsistencies, which are all pointed in the aforementioned articles.

There has also been a lot of confusion regarding who initiated the very idea of the termination. Kasparov claimed in his books Child of Change and Garry Kasparov On Modern Chess, Part 2: Kasparov vs Karpov, 1975-1985 that the decision to terminate the match was the result of a conspiracy between Karpov and Campomanes. These claims have slowly become truisms due to the fact Karpov has never has spoken about his role in the negotiations and the fact Campomanes himself also refused to talk about the matter in great detail. On the other hand, there are indications Kasparov himself initiated the idea before the 47th game, during the conversation with Campomanes’ representative in Moscow, Alfred Kinzel.

Thus, Winter’s 2005 conclusion regarding the Termination is topical even 13 years later:

„As matters stand, in 2005, is any consensus possible about the Termination, despite all the claims and counter-claims? We believe that few readers will disagree with the following summation:

-

The truth about the Termination has not been established, and may never be, and thus the only reasonable attitude is agnosticism;

-

Regardless of whether the decision taken by Campomanes was right or wrong, or a mixture of both, he handled the affair incompetently, both in Moscow and later;

-

The account by Kasparov in Child of Change was untruthful and self-contradictory;

-

Karpov has provided inadequate explanations to exonerate himself from suspicion;

-

A number of chess writers have handled the Termination decision inaccurately, and, above all, Keene has often attacked it with abject falsehoods.“

Who knows whether we will ever find out the real truth about the Termination and the events that happened behind the scenes.

In any case, the very first match between Karpov and Kasparov was concluded without a clear winner. In a way, it predetermined the infinite clashes that would await these two chess greats in the future.

Sources:

Edward Winter: Kasparov’s Child Of Change

Chessgames: Kasparov vs Karpov, 1984/1985

Chessbase: Kasparov pays tribute to Korchnoi

nytimes: Chess; Should chance decide the outcome of a match?

Garry Kasparov On Modern Chess, Part 2: Kasparov vs Karpov, 1975-1985

Garry Kasparov: Child of Change