After the endless Kasparov – Karpov battles in 1984, 1985, 1986, the time has come to organize the next World Championship cycle.

However, due to the clause that granted Karpov the right to return match in 1986, the natural course of the cycles has been interrupted. Kasparov was to defend his title only a year after his battle against Karpov in London and Leningrad.

The qualifying cycle was also somewhat different than before. Three Interzonal tournaments were held back in 1985. Four best players from each tournament, together with three best players from the previous cycle and one wild card, formed the line up for the Candidates tournament. Candidates tournament was held later in 1985. Four top players were seeded in the semi-final of the Candidates cycle and played a series of the match to determine the final winner.

After all these battles, Andrei Sokolov emerged as a winner and as a result, he was to play Anatoly Karpov in the final Candidates match, the winner of which would gain the right to challenge Kasparov. The decision to seed Karpov directly into the final was highly controversial and in the next cycle FIDE took a step back and seeded him in the quarterfinal instead.

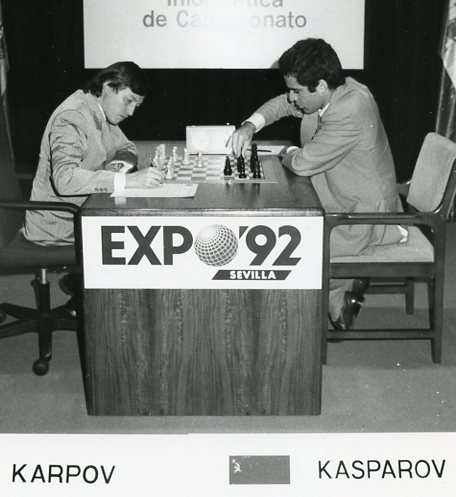

In any case, Karpov scored a convincing 7.5-3.5 victory and stage was set for yet another Kasparov – Karpov match, already the fourth in four years. The match took place in Seville in Spain, from October 12 to December 19, 1987.

By his own admission, psychologically this was the most difficult match so far for Kasparov. Having just won two matches in a row, he already felt that he has secured the title and it was very hard for him to tune for the full-fledged fight. He experienced similar difficulties like Smyslov in 1958 or Tal in 1961:

„The forthcoming clash was somehow very remote from my mind, and I couldn’t help wishing that I didn’t have to go through with it. Why did I have to play again? I’d already proved my superiority – I’d already won and then defended my world title… Although I realised that far more was at stake this time than in the previous matches, I really didn’t want to play the match, and my whole being rebelled against the very thought that I must once again, (for the umpteenth time!) mobilise myself for battle.

On the whole, my preparations before the match were of quite an adequate standard, but, alas, my playing mood did not match them. In the end my confused condition generated a fear of defeat, which had a paralysing effect on me.

Nikitin: ‘As the match approached, Garry became increasingly nervous; he kept saying that defending the title was far more difficult than winning it, and that he no longer had the same energy that drove him to the top. In an interview he said he would arrange a first-class burial for his opponent. This hackneyed method of intimidation, employed by boxers, merely confirmed his uncertainty…“

(Source: Garry Kasparov On Modern Chess Part Three: Kasparov vs Karpov, 1986-1987, pages 273-274)

His nervous state was apparent already in the 2nd game. After employing a prepared variation, he went on to think for 93 minutes (!) about his 9th move and lost rather convincingly in a double-edged, combative and typical ‘Kasparov’ position.

The players then exchanged blows in the 4th and 5th game, but after winning the 8th and 11th game Kasparov took the lead. He later said that the win in the 11th game did him a bad service; after finally taking the lead he thought that the match is virtually over and continued playing draw after draw in the second half in expectancy of the end of the match.

Even after the warning signal and loss in the 16th game, he didn’t change his approach and as a result, the end of the match turned out to be the most dramatic in the history of the World Championship matches.

In the 23rd game, after obtaining somewhat inferior, but perfectly defensible position, Kasparov, blundered heavily and went for the combination he and his trainers refuted during the adjournment session and lost the game.

Thus, before the 24th game, he found himself in a must-win situation; winning the last game was his only chance of retaining the title; a feat that only Emmanuel Lasker accomplished in his match against Schlechter, way back in 1910.

Kasparov’s thoughts before the game are best described by an excerpt from his book, How Life Imitates Chess:

„I can look back at my chess career and pick out more than a few crisis points, but only one Mount Everest. I would like to share the tale to investigate the means I used in winning the most important game of my life. …

After a tough, prolonged defense I suffered one of the worst hallucinations of my career and blundered to a loss in game 23. Suddenly, Karpov was up by a point and was only a draw away from taking back the crown he had lost to me two years earlier. The very next day after this catastrophe, I had to take the white pieces into a must-win game 24.

Caissa, the goddess of chess, had punished me for my conservative play, for betraying my nature. I would not be allowed to hold on to my title without winning a game in the second half of the match.

Only once before in chess history had the champion won a final game to retain his title. With his back against the wall, Emanuel Lasker beat Carl Schlechter in the last game of their match in 1910. The win allowed Lasker to draw the match and keep his title for a further eleven years. The Austrian Schlechter had, like Karpov, a reputation as a defensive wizard. In fact, his uncharacteristically aggressive play in the final game against Lasker has led some historians to believe that the rules of that particular match required him to win by two points.

When preparing for my turn on the other side of this situation, I recalled that critical encounter. What strategy should I employ with the white pieces in this must-win final game? There was more to think about than game 23 and game 24, of course. These were also games 119 and 120 between us, an extraordinary number of top-level encounters between the same two players, all played in a span of thirty-nine months.

It felt like one long match, with this final game in December, 1987, the climax of what we had started in September 1984.

My plan for the final game had to consider not only what I would like best but what my opponent would like least. And what could be more annoying for Karpov than my turning the tables and playing like Karpov?”

After a quiet opening, a dramatic series of events took place that could have changed the course of the chess history forever. Kasparov gained the chance to seize the advantage, but in the heat of the moment, he placed his queen on the wrong square, allowing Karpov an equalizing combination, with which he would most likely finally win a match against Kasparov. However, Karpov failed to capitalize on this chance and made a historic blunder. As a result, the game was adjourned in the position where Kasparov was a pawn up, which he managed to convert and retain his title.

This is what he had to say about this historic moment:

„While the adjournment session was in progress, the FIDE President Florencio Campomanes was holding a special meeting with the match organisers to discuss the details of the closing ceremony planned for that evening, and the unexpected problem of what to do if the session were to last its full six hours and the game were again adjourned. After all, the following morning all the interested parties were due to depart for home… The problem seemed a very real one, but both crises – chess and organisational were resolved in an instant, when someone rushed into the room where the meeting was taking place, and exclaimed: ‘ Karpov has resigned!’.

The ovation was undoubtedly the loudest and most prolonged (roughly 20 minutes) I had ever been awarded outside of my own country. […] This adjournment session was one of the most memorable moments in my life. The ex-champion’s defeat, dashing his almost accomplished dream of a return to the summit, was like a psychological knockdown“

(Source: Garry Kasparov On Modern Chess Part Three: Kasparov vs Karpov, 1986-1987, pages 426-427)

(The final moments of the 24th game)

Sources:

Garry Kasparov On Modern Chess Part Three: Kasparov vs Karpov, 1986-1987

Garry Kasparov: How Life Imitates Chess

Chessgames: Kasparov Vs Karpov, 1987

Quora: Vjekoslav Nemec’s answer to: What is the greatest chess match ever? Why?

Riveting retelling.