Note: This post is a part of the series of posts about chess openings. Each opening will have two posts devoted to it: „What every chess player should know about XYZ opening and „Best chess books about XYZ opening“. If you are wondering how I select the books I recommend or what other openings I have covered at the moment, I refer you to the reference post of the entire series.

Note 2: You can find the post devoted to the best chess books about the French Defence here.

Note 3: All .pgn files (game texts) used in this post are available to download for free on .pgn downloads page

Table of Contents

Introduction

The French Defence is a chess opening employed by the player handling the black pieces in reply to the advance of the king’s pawn by White, arising after the moves 1 e4 e6!?.

According to Batsford’s Modern Chess Openings, the French Defence was named after a correspondence game between the London and the Paris Chess Club in 1834, in which the French team employed this defence and scored a convincing win (even though the opening itself was known since the 15th century).

The French Defence belongs to the so-called Semi-Open group of openings, the characteristic of which is White playing 1 e4 on the first move and Black replying with anything else apart from 1…e5 (which would lead to Open Games).

The intention behind the move 1… e6 is clear – Black delays the fight for the center for one move and prepares to move his queen’s pawn on the next move (2… d5). Black avoids the symmetry from the very first move and allows White to grab space with eventual e5 advance, claiming that he will be able to undermine White’s advanced center later in the game.

The French Defence is, therefore, regarded as a counter-attacking opening, utilized by ambitious players who want to play for the win with the Black pieces. Considering that Black does concede space, it is sometimes considered risky. But in the majority of games, it will lead to a sharp, uncompromising and double-edged battle 1

In the remainder of the post, we will first make a brief overview of the common opening variations of the French defence. Then we will describe typical pawn structures resulting from these variations and we will describe typical plans, ideas, and maneuvers connected to the pawn structures in order to increase our understanding of the resulting middle game positions.

Finally, we will wrap this article up list of prominent players who have played the French Defence throughout their life.

Hope you will enjoy it and find it useful!

An overview of variations

After 1 e4 e6, 9/10 games will see White advancing his queen’s pawn and Black replying in the same fashion – 2 d4 d5.

This can be considered as the main tabiya 2 of the French Defence. Now White is at the crossroads and has 4 big moves at his disposal. We will mention them in turn.

The Winawer Variation

In the diagram position above, by far the most theoretical (and critical) move is the move 3 Nc3:

This move defends the e4 pawn and also influences the important d5 square (in contrast to 3 Nd2, which we will examine later). The drawback is that the knight on c3 obstructs the pawn on c2 (preventing the reinforcing c3 move).

Also, the knight can easily be pinned after 3… Bb4, which leads to one of the main opening variations of the French Defence – the razor-sharp Winawer Variation:

This variation has fascinated chess-players for almost 100 now. It leads to a complicated tactical melee, where both sides have to be ready to make ‘ugly-looking’ moves and sacrifice material. White usually advances e5 and plays on the kingside, while Black counter-attacks on the other side of the board.

The Classical Variation

Of course, Black is not forced to enter the Winawer variation. Apart from the minor third moves after 3 Nc3, such as 3… Nc6!?, 3 ….a6!? and 3… h6!?, a big theoretical move is the „simple“ development of the king’s knight with 3… Nf6, leading to the so-called Classical variation:

The Classical Variation usually leads to a more positional play (compared to Winawer) after 4 e5 Nfd7, entering the so-called Steinitz variation:

although 4 e5 is also not forced – the development of the bishop to g5 – 4 Bg5 is also fairly common, after which Black plays either the more fighting 4… Bb4 (McCutcheon variation), 4… dxe4 (Burn Variation) or 4…Be7 (which may lead to the dangerous and fascinating Alekhine-Chatard attack arising after 5 e5 Nfd7 6 h4!?).

The Tarrasch Variation

As we have seen above, White players playing 3 Nc3 need to be prepared for both 3…Bb4 and 3… Nf6, which is the reason why 3 Nc3 is considered to be most difficult and demanding move to play.

It is not surprising that many players choose the alternative development of the knight on the third move – 3 Nd2 – leading to the so-called Tarrasch Variation:

The idea behind the move is simple. White defends the e4 pawn, doesn’t block the c-pawn and renders any potential Bb4 pin useless. The downside is that the knight on d2 obstructs the bishop on c1 and doesn’ control the d5 square.

Black now has two main moves at his disposal – 3… c5 or 3… Nf6. In both cases, the play is slower, more strategical and positional in nature than in the Winawer variation.

The Rubinstein Variation

White is not the only one who has a choice in the main lines of the French Defence. If Black doesn’t want to learn a lot of theory and differentiate between 3 Nc3 and 3 Nd2, he can always exchange his d for the enemy e-pawn early in the game with 3… dxe4:

[Event “?”]

[Site “?”]

[Date “2020.03.21”]

[Round “?”]

[White “The French Defence”]

[Black “The Rubinstein Variation”]

[Result “*”]

[ECO “C10”]

[PlyCount “6”]

1. e4 e6 2. d4 d5 3. Nc3 dxe4 {The starting point of the Rubinstein Variation.

Note that Black can play this irrespective of whether the White knight is on

c3 or d2 – White doesn’t have a better move than recapturing himself.} *

This leads to the so-called Rubinstein Variation. It is considered somewhat passive for Black (less space and influence in the center), but very solid (no weaknesses).

The Advance Variation

Instead of developing the knight, White can choose to advance his e-pawn on move 3 with 3 e5, highlighting one of the reasons why the French Defence belongs to the so-called Semi-Open games:

The Advance Variation leads to what is considered the 'proper French' pawn structure 3 and leads to maneuvering play behind the pawn chains.

It was considered as the most principled variation in the past, but has lost its popualrity in the modern era (although some players – like Grischuk and Svidler – still play it on the highest level).

The Exchange Variation

If White wants to avoid all risk whatsoever, he can always consider taking on d5 on move 3 with 3 exd5, leading to the so-called Exchange Variation:

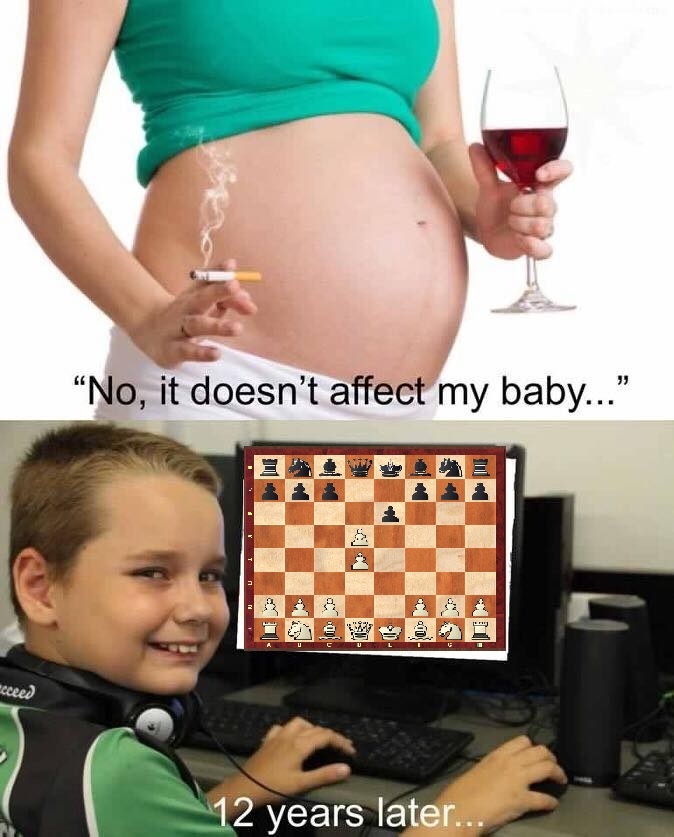

The Exchange variation immediately leads to a symmetrical pawn structure and has a rather drawish reputation. Many French defence players dislike playing against it – especially when they are faced with a lower-rated opponent the expect to beat.

On the other hand, it is not the most ambitious approach by White (he can hardly count on a serious advantage) and is widely regarded as tasteless and 'cowardly', as the following meme testifies:

(I am sorry if you expected something funny, I should have warned you about the kind of memes I make 😀)

Miscellaneous Variations

Last but not least, since French is relatively flexible opening, there is a bunch of miscellaneous lines that do exist, but are not encountered as often as the main variations.

By far the most serious of these alternatives is the move 2 d3, leading to the Fischer's favourite King's Indian Attack:

while other options such as 2 b3!? or the Wing Gambit 2 Nf3 d5 3 e5 c5 4 b4!? do have a right to exist, as well.

An overview of typical pawn structures

After getting acquainted with the introductory opening moves of most important variations of the French Defence, it is time to learn something about the typical French Defence middlegame.

Before getting to the concrete typical plans, ideas and maneuvers, I have decided to take a moment to reflect on the typical pawn structures arising from different variations of the French Defence. I think that middlegames plans and ideas are tightly connected to the resulting pawn structure and that understanding of the structure determines the understanding of the opening as a whole (and the strength of the player).

Therefore, I have singled out four most common pawn structures resulting from the French Defence.

c3+d4+e5 by White vs e6+d5+c5 by Black

Typical of: Winawer Variation, Classical Variation, Advance Variation, Tarrasch Variation

The characteristic pawn structure of the French Defence, often called “The French” structure. White grabs space on the kingside with the move e5. Black tries to undermine the pawn chain at its base (d4) with the c5 advance, to which White replies with c3 (or has a pawn on c3 already in case of Winawer variation).

In subsequent play White tries to utilize his kingside space advantage, while Black tries to attack the center by attacking c3 or d4 (or undermining it with f6).

c3+d4+e5(+a3) by White vs e6+d5+c4 by Black

Typical of: Winawer Variation, Advance Variation

A subvariation of the previous structure. In certain lines of the Winawer and Advance variations, Black closes the French structure with c4. This results in a very closed position, where both sides maneuver behind their pawn chains.

White tries to win on the kingside where he has space (f4-f5 advance) or to undermine the structure on the other side with b3. Black usually tries to bring his pieces to the kingside and use the opening of the position to create threats against White’s king.

f4+e5 by White vs e6+d5 by Black

Typical of: Classical Variation

A typical pawn structure for the Classical variation, where Black manages to get rid of the pawn on d4. On one hand, it weakens White’s pawn chain, on the other hand, it gives him the d4 square for his pieces.

In the resulting play, White usually tries to advance f5 (and potentially f6) and mount attack on the black king. Black, on the other hand, tries to advance his queenside pawns and create play on the opposite side of the board.

c2/c3/c4+d4 by White vs e6+c6 by Black

Typical of: Rubinstein Variation

The Rubinstein Variation leads to a completely different pawn structure where White's d-pawn faces the pawns on e6 and c6 – the so-called „scissors“. The similar structure (resulting from the exchange of the White's e-pawn and the Black's d-pawn) can arise from many other openings (Caro-Kann, Scandinavian, Philidor, Steinitz Ruy Lopez etc.). GM Alexander Delchev (with whom I took 2 private lessons way back in 2014) called it the „Spanish Structure“.

In general, White's position is considered to be slightly better due to his space advantage and free piece development. His active ideas include queenside advance with b4-b5 and/or timely break in the center with d4-d5. His pieces can often spring to life and create direct threats against the black king.

However, Black's position is very solid and he has very clear plans (connected with c5 or e5 pawn break). Therefore, many Black players decide to go for this structure – and enjoy good results.

c2/c3/c4+d4 by White vs d5+c7/c6 by Black

Typical of: Exchange Variation

Last but not least, the dreaded symmetrical structure arising from the Exchange Variation. The same pawn structure can arise from several other openings (such as the Petroff or the Berlin Ruy Lopez).

Due to the symmetry and lack of pawn weaknesses, this position is considered to be very drawish (and French Exchange very boring). White has some ideas connected to the kingside expansion, or with the creation of the weaknesses on the queenside (with Qb3 or c4, for example), but objectively he can't hope for much. For Black, it is very difficult to create imbalances and play for the win, though.

An overview of typical plans, ideas and maneuvers

The French Defence one of the most complicated and difficult openings to handle for average club players. Due to the variety of resulting pawn structures and the fact the typical French Defence structure is locked, leading to maneuvering, non-forcing play, understanding plays a crucial role. Playing behind long pawn chains, strategical maneuvering, ragged play, tactical variations, open center, closed center, etc…You name it - French Defence features it all.

The complexity and the nature of play are reasons why many club players find it difficult to handle (especially with White pieces).

Nevertheless, there are some common strategical concepts and ideas typical of French defence play that might help you to handle it more successfully.

I will try to describe them in the remainder of this answer and connect them to the opening variation of the French chosen.

It is important to retain the flexibility of thinking and not to take them as axioms. Thinks of these French laws as rules of thumb; they are not to be followed blindly and are highly dependant on the position on the board.

Black’s light-squared bishop is a problem piece in the opening

Considering that Black erects his pawn chain on light-squares (e6-d5-c4), his light-squared bishop on c8 is often restricted and turns out to be a problematic piece.

The fight “for-and-against” the development of the light-squared bishop is one of the central ideas in the French Defence and the evaluation of the position often depends on who wins this battle. It is often considered that once Black solves the problem of his bishop, he has equalized (at the very least).

However, there are certain caveats. There are some variations where Black can head for an early exchange of the light-squared bishops. You might think it solves the problem immediately, but it usually costs some time(tempi) and creates other type of problems (mainly connected with lack of development).

This is indirectly proven by the existence of the so-called Advance variation of Caro-Kann:

Since his bishop is developed outside of the pawn chain, on the active g6-b1 diagonal, this is often regarded as the “good version” of the French Defence. However, the practice has proven that the early development of the bishop has its drawbacks – mainly connected to the inability of the bishop to return to the defence of Black’s queenside, which might become vulnerable.

Therefore, don’t just blindly follow the rule and try to exchange/solve the problem of your bishop. As usual in chess (and life) – timing is of the essence.

White erects a c3-d4-e5 pawn chain and tries to maintain it as long as possible.

Typical of: Advance French, Steinitz Variation, Winawer Variation, Tarrasch variation

In almost all variations of the French, White tries to gain space in the center. If he manages to stabilize and gain control there, he might use his space advantage to attack the weaknesses on the kingside.

Most typical moves include Qg4, Nh3-Nf4, h4-h5 followed by Rh3, etc.

Black tries to undermine the center with the c5 and f6 breaks.

Typical of: Advance French, Steinitz Variation, Winawer Variation, Tarrasch variation

This is tightly connected to the previous point. When White errects a central pawn chain, Black has to try to break it somehow. With c5 Black tries to put pressure on d4, with timely f6, Black tries to undermine White’s position from the other side.

White tries to plant a knight to d4.

If this knight is maintained and supported, White should get some advantage. Because this often comes in combination with the typical “bad French bishop”, even the driest and simple positions don’t lead to automatic equality.

White avoids castling and keeps his king in the center

In many lines of the French Defence, White (and Black also) don't necessarily castle, but prefer to keep the king in the center. A very famous example is the very first game between Mikhail Tal and Mikhail Botvinnik from their 1960 World Championship Match:

White plays a4, followed up by Ba3 (even at the cost of a-pawn)

Since his pawns are on dark-squares (c3-d4-e5), White often has trouble finding a useful role for his own dark-squared bishop. One possible way of developing it is by developing it on the a3-f8 diagonal. That is why White often plays a4 to open the a3 square for the bishop – even when it costs a pawn. The following game between Leonid Stein and Tigran Petrosian is a beautiful example:

Therefore, Black often prevents White from playing the a4 advance whatsoever – for example in the following line of the Winawer:

Model players

Last, but not least, in order to get acquainted with the opening (and to study it properly) it is important to look at th model games. Fortunately, throughout the history of the game, several players have been great proponents of the French Defence. On this list, we will mention a few notable names (in no particular order):

- Mikhail Botvinnik – sixth World Champion was a huge champion of this opening and played it almost during the entire life (he switched to Caro-Kann toward the end of his active years)

- Viktor Korchnoi – „Viktor the terrible“, one of the greatest players never to become World Champion, also played the French during his entire life. It perfectly suited his fighting, counter-attacking style.

- Tigran Petrosian – the ninth World Champion also played a hell lot of French Defence games throughout his life.

- Nigel Short – the French was the main weapon of the former World Championship finalist, even though he didn't dare venture it in the match against Kasparov in 1993.

- Wolfgang Uhlmann – a strong German grandmaster who played the French defence almost exclusively and later wrote a book about the opening on the basis of his games.

- Nikita Vitiugov – a member of the 2700 club and a huge French Defence expert.

Honorable mention: Vassily Ivanchuk, Veselin Topalov, Magnus Carlsen, Lev Psakhis, Alexander Morozevitch, Varuzhan Akobian, Rafael Vaganian, Smbat Lputian..

... and many others! 🙂

Conclusion

Phew! We have finally reached the end of this lengthy introductory post to the French Defence.

I hope you have enjoyed it, found it helpful and that it has provided you with an idea of what the French Defence is all about.

Let me know what you think about it and about this format, and also which opening would you like to see covered next 🙂

Until next time!

- With the exception of the so-called Exchange variation, which is considered fairly drawish. But then again, there is no chess opening where White is unable to dull the game if he wishes to do so.

- An Arabic term taken up by chess players, depicting a standardized opening position

- c3+d4+e5 by White vs e6+d5+c5/c4 by Black. See the section about pawn structures for more details.