The following article is a guest post by Nikolaos Ntirlis. Nikolaos is a strong correspondence player and a renowned book author and some of you might know him from his opening theory threads he regularly publishes on his X/Twitter.

But apart from being “the chess guy”, Nikolaos also has a profound interest in (business) philosophy and ethics. A couple of weeks ago, he reached out to me and expressed his interest in writing a guest post on the topic of ethical behavior within the chess world. Since I have written about similar topics in the past, I thought it was an important and challenging topic, and since I had several positive interactions with Nikolaos in the past, I gladly accepted his offer.

Once he delivered his work, I knew it was the right decision. Because the article in front of you was one of the most interesting and enlightening pieces of writing I have seen from someone within the chess world. 1 Apart from teaching me a lot about ethics and philosophy, it has also made me re-examine how I approach complex moral issues and made me realize they can be approached from many different angles.

I do hope you will find it as enlightening and interesting as I did. Or at the very least, that you will learn something new about giants such as Plato, Kant, or Aristotle.

And now, without further ado, I give it to Nikolaos.

Table of Contents

Introduction

The Motivation For This Article

A typical day for a chess fan on Twitter these days seems to go like this:

- Start scrolling

- Read a few tweets about the new drama of the day

- Become angry with the person who tweeted something controversial or with those who criticized them

- Repeat the same cycle the next day…

I am certainly not the first one to notice it. The chess world is in a permanent state of controversy. The usual suspects these days are Hans Niemann, one of the biggest prospects of US chess right now, and the former world champion Vladimir Kramnik. But these controversies often involve a cast of characters ranging from Women Grandmaster Dina Belenkaya to the GOAT (?) Magnus Carlsen himself.

As these dramas unfold, everyone forms an instant opinion on who is right and who is wrong. But unsurprisingly, these opinions clash, with people found on both sides of the argument, disagreeing on the fundamental ethics of the situation.

Even when they agree, they may have different reasons for their judgments. The next day, when a similar situation arises, the same individuals might evaluate the case differently, based on personal preferences and biases.

Chess fans are not unique in this regard. It is a common occurrence in every aspect of social life, both on social media and out of them (what some people call, real life). Think about the last time you found yourself among relatives, discussing politics, and you’ll know what I mean…

However, what sets chess players apart is their capacity to understand this: Ethics are similar to chess openings!

Over the centuries, a huge body of theory has been developed in a branch of philosophy called Ethics. In the same way we study a book or a course and learn the intricacies of the Spanish or Italian opening, we can study philosophy and ethics. We can use the tools that great thinkers have developed to analyze a chess drama and evaluate, similarly to Stockfish, who is right or wrong.

Ethics, along with another branch of philosophy called aesthetics, is often referred to as ‘value theory’ because it helps assess the value of how good or bad something is.

Imagine something like this:

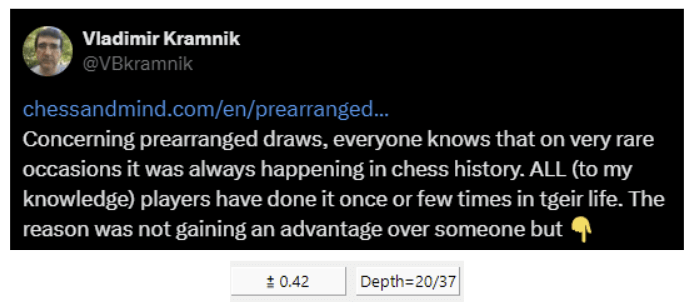

Imagine being able to evaluate the above argument in terms of “centipawns” with an engine called Ethicsfish. Please email me if you want to invest in creating such an engine!

So, I decided to write this article to discuss the analytical tools that ethical theories like consequentialism, deontological ethics, contractarianism, and virtue theory can offer us.

We’ll see specific examples and analyze them with the help of these tools, like a grandmaster scrutinizing a complex position, and see how they might offer clarity amidst the chaos.

The goal of this article is twofold. Primarily, I aim to inspire you to examine moral issues from diverse perspectives. As is often the case with philosophy, the process of studying how great minds approached and analyzed a particular topic can be intellectually gratifying. However, at the end of the day, we can adopt the frameworks or aspects that resonate most with us. So, I invite you to open your mind, analyze moral dilemmas through the lenses of different ethical theories, and ultimately retain what makes the most sense to you.

My second goal is a bit riskier and more challenging. Still, I want to accept the invitation from my editor to attempt to provide you with a formula, an algorithm of sorts, that you can employ when analyzing real-life moral dilemmas.

Of course, in the modern ongoing discussion between philosophers, many (and much more sophisticated) such formulas get created. But, I think that it will be instructive to see an amateur philosopher like me, trying to construct one. It will be a similar experience to watching someone streaming their chess games online. The games are not perfect, but you can see the struggle of someone who possibly is a bit ahead of their audience in terms of knowledge and experience.

Thinking about Ethics – Enter Metaethics!

Before we start the discussion on ethics – the branch of philosophy that studies what is right and wrong behavior, let’s take a minute to talk about metaethics, the study of the very foundations of morality itself (yes, it’s going to be that kind of journey…).

Among those without academic training in ethics 2, the most common metaethical view is the belief that there are moral facts, more or less the same way there are scientific facts.

In this view, some things are just wrong, and others are indisputably right. That’s what the gut intuition of most of us tells us. That’s how we understand the world since we were kids.

However, that’s one of the easiest things to argue against. If there were just moral facts, where would they come from? Maybe that’s an easy answer if you are a religious person, but it is a subject of constant debate. 3

Can we test and falsify these moral facts as we do with scientific facts? And, regarding scientific facts, we can arrive at some consensus. Why can’t we do the same with ethics? 4

But, if there are no moral facts, what does this mean? Could two moral views be correct at the same time? And what are they based on? Our feelings? 5 Our reason? Our social environment?

This is often called the “Grounding Problem” in Ethics. We need some rule, some assumption, something to hold on to, on which we can build our ethical theory. That’s what thinkers have done for thousands of years now. So, each of the theories, the analytical tools we’ll talk about, has a foundation. If you don’t accept this foundation, the whole theory collapses. 6

So, let’s dive into the ethical theories…

Four Big Ethical Theories

Consequentialism – The Sicilian Defense

- Foundation: What matters is the outcomes of actions.

- Why similar to the Sicilian: In the Sicilian, we tend to have complex positions where the consequences of every move must be carefully calculated.

Consequentialism is an ethical theory that evaluates actions based on their consequences. Nothing is right or wrong on its own, and intention doesn’t matter. All that matters is the outcomes. It is a simple theory to understand, and incredibly practical.

Consequentialism is becoming the dominant framework in domains like public policy and business management today. 7 It is very convenient to link it with finance and economic indicators and measure its results.

If you feel that your government is frequently making ethically wrong decisions, not caring about certain groups of people, for example, that’s because most administrations today adopt a consequentialist perspective. But, be careful. This doesn’t mean that you are always right, thinking that an administration is wrong. It might be the case of missing the whole picture, and not understanding the overall consequences. 8

This theory is often associated (or confused) with utilitarianism, a specific form of consequentialism that says the right action is the one that maximizes happiness for most people (or minimizes the pain). The idea of measuring things based on pleasure and pain is called hedonism.

So, consequentialism + hedonism = utilitarianism. 9

Consequentialism’s main critiques point out that the theory may lead to ignoring the rights or well-being of some for the benefit of the many.

But on the personal level, there is another, at least, equally serious issue. In complex situations, it is very difficult to assess the implications of an action. We simply don’t have access to the full picture, no matter how hard we try.

To understand this theory, let’s look at it through the lens of a famous philosophical dilemma: the trolley problem.

The trolley problem and consequentialism

The basic scenario of the trolley problem is that a runaway trolley is heading toward five people who are tied to the tracks, and the only way to save them is to divert the trolley to another track where one person is tied.

You are the one who can pull a lever that will switch the trolley to the other track, killing one person but saving five. Would you do it?

The theory requires that you pull the lever. You kill one person to save five.

But, doesn’t this mean that you are choosing to take the life of an innocent person? After all, it’s not your fault that the situation is so terrible. You shouldn’t have to get blood on your hands to try and fix it. Right?

So, you see that consequentialism is a very demanding moral theory. We live in a world where sometimes people do terrible things. And, if we’re the ones who are there, and we can do something to make things better, we must. Even if that means getting our hands dirty.

But, things are not always that simple. What if this one person we decided to kill is important, let’s say an influential scientist, or has a family and kids that will suffer from this loss, while the five people are old and sick with no relatives left? In this case, wouldn’t the consequences be worse if we switched the trolley to that one person? How could we know? 10

The trolley problem sounds too abstract and hypothetical? Let’s try to take a step further and apply the principles of consequentialism to a real-life example from the chess world.

Kramnik and the cheating problem in chess

Should Kramnik point out potential cheaters, risking some false positives?11

A consequentialist will argue that such an important figure has so much power in the community that he can change things for the better. And even if some people get negatively affected, we should judge his actions based on the overall outcome and if that will be positive, for example, if the cheating problem in chess gets reduced or solved. 12

As you can see, that’s much more difficult for an individual to do than say a big organization like chess.com or FIDE. As mentioned above, it is very difficult for an individual to assess the implications of an action in a highly complex situation. A big organization might be able to do a more informed measurement of these outcomes.

Deontological Ethics – The Nimzo Indian Defense

- Foundation: Moral rules derived from reason which we should feel a duty to follow.

- Why Nimzo-Indian: Logical, principled, where the moves are guided by sound reasoning.

When you ask someone why they think a certain decision or action is bad, you might expect a profound answer. But often, you’ll get a “because it’s… bad.” And if you feel that that’s a lame answer, according to deontological ethics, it’s not!

“Deontological” comes from the Greek word “deon,” meaning obligation. It’s a branch of ethics that’s all about duty and rules. It insists that you should always do what’s right, no matter the consequences.

But where does this sense of obligation come from? If you believe in God, then this question has an easy answer. That’s what it is called “Divine Command Theory”. However, philosophers have been poking holes in this theory since ancient times. 13

Consequently, even theologians found ‘Divine Command Theory’ lacking, leading them to develop alternatives such as Aquinas’s Natural Law Theory. 14 This theory has become the foundation of Catholic Ethics to this day.

But, deontological theories based on divine or natural definitions of right and wrong are way older than that, even older than philosophy itself. Take Homer’s epics, for instance, where doing the right thing was all about bravery and heroism, and about keeping the cosmic balance—a central theme in many ancient cultures.

The issue here is that philosophy is essentially humanity’s noble quest to solve problems using reason and logic, rather than relying on faith or superstition. So, we’re focusing on ethical systems grounded in reason here. And surprisingly, ethical systems that are based on the “obligation of doing the right thing” that are purely based on reason, are a much more recent development.

Typically, deontological ethics is connected with one name: Immanuel Kant. And I have to admit that despite my best efforts, I don’t understand Kant. So, take the following with a pinch of salt—I might be missing the mark. 15

Obligations based on reason

Kant was all about morality being rooted in reason and reason alone. Not feelings, not preferences, not cultural backgrounds, and certainly not divine memos. He believed that an action is morally sound only if it’s done out of duty, not self-interest or for any potential outcomes.

He laid down his moral laws, the “categorical imperatives,” which are like the universal rules everyone should follow, no matter their wishes or situations.

Two of the most famous such laws, in the way I understand them, are:

“Live by the rule that you’d be okay with everyone else following too.” 16

Consider a chess game where using an engine will give you an edge. But, what if everyone did the same? The game would be ruined. According to Kant, that’s why cheating at chess is a no-go.

That’s a very practical way to understand if something is right or wrong. That’s typically one of the lessons on morality we learned from our parents and teachers during childhood. 17

“Always treat people as valuable in themselves, not just as tools to get what you want.” 18

This means seeing yourself and others as individuals with worth and dignity, not just as a means to your ends. 19

Kant also defined what gives human beings dignity. And that’s autonomy. Think about it this way. What happens when we lie to someone? We’re messing with someone’s ability to decide based on truth. Or because we want to use someone to do something for us. Intentions are a central part of deontological ethics. The reason we do something, matters.

I didn’t use the example of lying out of an accident. Kant was famously rigid in his stance against lying, arguing that it is never morally acceptable, even in situations where lying might prevent harm.

The catch with deontological ethics is this: if you stick to the rules without weighing the consequences, you could inadvertently cause more harm than good. It’s a common critique that such unwavering commitment to rules, regardless of the outcome, can sometimes lead to results that clash with our innate sense of morality.

Are pre-arranged draws in chess immoral?

Are pre-arranged draws in chess immoral? To answer this, we can apply Kant’s categorical imperatives to see if such actions hold up morally.

First Imperative: “Live by the rule that you’d be okay with everyone else following too.”

If every player pre-arranged draws, the essence of competition would vanish, rendering a chess tournament meaningless. It’s pretty clear that if such behavior were universal, it would undermine the very nature of the sport.

Second Imperative: “Always treat people as valuable in themselves, not just as tools to get what you want.”

That’s a bit tougher to apply, but one possible way to think of it is that pre-arranging a draw could be seen as using the opponent merely as a means to an end. That’s securing a favorable outcome without the genuine effort of play. It doesn’t matter if both sides do it for the same reason. The reason is bad, so the action is immoral.

This fails to respect the dignity and autonomy of both players as rational agents capable of competing.

In conclusion, pre-arranged draws in chess seem to fail Kant’s moral test on both counts. They disrupt the integrity of the game and treat participants not as autonomous individuals but as tools for achieving a predetermined result. Therefore, from a Kantian perspective, pre-arranged draws could indeed be considered immoral.

Still, many chess players don’t think of it this way. I think that the next ethical theory may explain this phenomenon.

Contractarianism – The Slow Italian Game

- Foundation: It’s based on an unspoken social contract that dictates moral conduct.

- Why Slow Italian: It’s like this slow-paced Italian opening where players agree not to launch into early attacks, following instead established opening principles for developing and castling early.

People often think of contractarianism as a political idea, but it’s also useful when talking about ethics.

It suggests that everyone in society has an unspoken agreement to follow the rules. This may refer to laws, customs, or traditions that guide their interactions.

Take the handshake before a game as an example. Expecting a handshake before a chess game is a tradition that goes beyond the official rules. It’s been a sign of good sportsmanship for ages, showing respect for the game and the opponent. If someone refuses to shake hands, it’s seen as disrespectful and leaves a sour feeling among players.

However, contractarianism isn’t without its critics. It’s been pointed out that it fails to account for societal evolution. If we always follow tradition, and that’s what is considered the right thing to do, then how can societies become better?

The social “contract” is believed to benefit the members of the society it serves, but as societies evolve, these agreements may become outdated. Yet, there’s often a sense of obligation to adhere to them.

When Kramnik had to justify why top-level players don’t think that pre-arranged draws are a bad thing, that’s what he came up with:

This is contractarianism. Top-level players have agreed that this is accepted behavior. Everyone has done this from time to time and expects everyone else to do this from time to time as well.

This is contractarianism. Top-level players have agreed that this is accepted behavior. Everyone has done this from time to time and expects everyone else to do this from time to time as well.

Kramnik linked to the following article, where opinions on the matter are collected from top-GMs. For example, Grischuk offered another contractarian perspective:

“I don’t see an issue with them, honestly […] It’s part of chess culture for a century at least”.

By now, you can see how different theories may attach a different moral value to an action.

- For a contractarian, pre-arranged draws are acceptable.

- For a Kantian, that’s completely unacceptable.

- A consequentialist might evaluate them on a case-by-case basis. For example, a pre-arranged draw in a critical match could be deemed unethical, but the same action between two hobbyists at a local tournament might be considered harmless.

Contractarian thought fundamentally examines the reciprocal relationship and obligations between the individual and the community they are part of.

On one hand, by living within and benefiting from an organized community, individuals are expected to uphold certain moral duties and responsibilities as their part of the social contract. 20

On the other hand, this social contract is a two-way street – just as individuals have duties to the community, the community itself has a profound moral obligation to respect the fundamental rights, and dignity of each individual member.

So, we should choose. Who comes first? The individual, or the community? Luckily, most philosophers agree on that. The guarantying of inviolable individual rights should come first.

Virtue Theory – The Ruy Lopez

- Foundation: Developing good character traits

- Why the Ruy: Like the Ruy Lopez, virtue theory is a classic. It’s been around since the start of philosophical thinking, but it still is trendy and influential.

Let’s say a friend asks you for help. What would you do?

- From a consequentialist view, you’d want to think about the possible results of helping them. If assisting is unlikely to cause harm and could lead to good outcomes, then you should probably help.

- Taking a deontological approach, you might be guided by the moral principle of treating others how you would want to be treated yourself, meaning helping your friend in need.

On the other hand, a virtue ethicist would think that helping a friend is the obvious thing to do. It is a matter of compassion and generosity. Why should we make any calculations?

From a virtue ethics perspective, the primary consideration is not the consequences of the action or adhering to a moral rule, but what an action says about one’s character.

Just like you don’t think about breathing or playing the first moves of your favorite opening, try to be a person who does good things without having to think hard about it.

Virtue ethics is just a different way to see things. And, as we’ll see, this can solve many practical problems.

Consequentialism, deontological ethics and virtue theory

For the most part, consequentialism, deontological ethics, and virtue theory agree on what’s right or wrong. They may not agree on the “why” and the “how you get there”, but for any reasonably simple real-life situation, choosing just one of these theories to guide your thinking, will be enough. Also, each one of these theories does consider what is foundational for another one, just not as something central.

For example, in the Kantian approach, there is space to consider outcomes, as there is space to consider individual rights for a consequentialist. Just, these considerations are not the central part, the foundations of these theories.

Most discussions in the academic sphere on ethics today revolve around the “outcome vs obligation” question, and what is the right mix. But in some other disciplines, virtue theory is the central topic of discussion. Some notable examples are psychology, education, and business. 21

As Kant is the main person who we should always mention when we discuss deontological ethics, for Virtue Theory, this person is Aristotle, who taught what we will discuss below around 350 BCE, or about 2,400 years ago.

Aristotle and virtue theory

First of all, why should we work daily to develop our character? According to Aristotle, that’s how we reach the state of “eudaimonia” (well-being). For the philosophers of Aristotle’s time 22, answering the question “how to live a happy life” had a central part in their thinking. They believed that people with good character are not only good about themselves but for everyone around them. So, there was a strong link between personal development and how this affects the society. 23

Aristotle thought that human beings have a natural tendency to develop virtues24 that help them achieve eudaimonia. He classified them. The “cardinal virtues” that everyone should develop, are prudence, justice, temperance, and courage. You can choose to develop more, those that make the most sense for you, but these four, are a must.

According to Aristotle, having the virtue of something sits at the middle end of two extremes which he called “vices”: one of excess and one of deficiency.

For example, the virtue of courage is a mean between rashness (excess) and cowardice (deficiency). 25

Socrates, before Aristotle, taught that virtue is a form of knowledge and that ignorance is the cause of wrongdoing. According to Socrates, when someone behaves immorally, he is doing it out of ignorance. He/she isn’t educated enough. So, instead of punishing this individual, they need to go back and learn what is good and bad.

Aristotle disagreed with the idea of virtue = knowledge. He believed that becoming a virtuous person isn’t about reading books, but it means practice. To do rather than know.

He also suggested observing. To find “good influencers”. Those who have developed these virtues, and follow them as examples.

Discovering Your Values

Aristotle’s teachings are still relevant today. But, besides these basic virtues, we should create and use our own “ethical compass” by identifying our own set of virtues, or what we usually call them today: values. These values act as a personal guide, helping us when faced with moral dilemmas. And as Aristotle said, just defining them, isn’t enough. We need to work daily to develop them and live by them.

To identify your core values, reflect on moments when you felt particularly proud or ashamed. These feelings can reveal what truly matters to you.

Following Aristotle’s advice, consider the qualities of people you admire. Their guiding principles can help shape your own set of values.

Start by writing a comprehensive list. Initially, it’s okay for this list to be extensive. Gradually narrow it down to the 3-5 values that feel most authentic to you.

Once you’ve made your list, consult with trusted individuals, like friends or family. See if they associate these values with you when you share your list. If they don’t, it’s time to reassess. Are these values a true reflection of who you are? Why might others not perceive them in you?

This method is widely used in business management training 26 and by marketers when they’re defining a brand’s identity.

Companies need to set their values as well. I have learned through experience as a manager, that you cannot anticipate anything that can happen during the communication with a client, or inside a team. Companies have “standard operating procedures” (known as SOPs), but always something happens that gets you out of the normal procedure. What should you do then? This is when the company’s values come to the rescue! 27

Put simply, when things are unclear, following your values will guarantee that you will not mess up. Things might end up badly, but you’ll know that you did the best you could. From an ethical point of view, you did the right thing. 28

An Ethical Guide For Chess Players

So far in this article, I have described the analytical tools with which each of the different ethical theories described above provides us. I have also shown how these tools can be applied to analyze deep and complex issues and how different ethical theories can have different viewpoints regarding the morality of a specific issue.

In the final part of the article, I would like to try to go a step further and build upon these tools/theories to create an algorithm for the potential “EthicFish” engine, which would enable us to analyze and evaluate complex moral issues. And then apply that very same algorithm to a concrete, real-life example that caused a lot of controversy at the time.

Theoretical Framework: Nikos’ Step-By-Step Guide To Ethics

Step 1: Consequentialist Consideration

First, carefully consider the potential consequences of your action or decision on all those who may be affected. Strive to maximize overall well-being, minimize harm, and promote the greater good.

However, if the outcomes are unclear or too difficult to predict, move to the next step.

Step 2: Deontological Principles

Apply the test of universalizability – could the reasons behind your action be willed as a universal law? Additionally, respect the autonomy, rights, and dignity of all persons involved.

If these Kantian principles do not provide a clear resolution, proceed to the next part.

Step 3: Social Norms and Traditions

Examine relevant laws, cultural traditions, and established practices pertaining to the ethical dilemma.

If this exploration still does not yield a satisfactory solution, advance to the final step.

Part 4: Personal Virtues and Values

Ultimately, draw upon your virtues, and values to guide your decision. Strive to act with integrity, compassion, and courage. If needed, seek advice from individuals you regard as morally exemplary.

Practical Application: How do female chess influencers promote chess?

To see how we can use the ethical guide described above in practice, let’s try to apply it to a real-life example. The following post on X by WGM Dina Belenkaya caused a lot of controversy at the time when it was posted and became a topic of many debates:

Should female chess influencers promote this type of content? Do they do it for the clicks and to get FanHouse subs, or to promote female chess players’ empowerment? Or we shouldn’t care, as they have the right to do whatever they want?

Let us use our ethical formula, to see if we can get an answer.

Step 1: Consequentialist Consideration

This type of content brings eyeballs to female chess. The above post had more than 600k impressions. That’s a positive. But, some female chess players didn’t feel well with it. Please remember, that if they were right to feel offended, or not, doesn’t matter at this point. What we know, is that a significant number of women didn’t like this content and expressed it openly.

Do we know if this post brought financial benefits to those involved? Directly, possibly yes, and that should be counted as a positive. Do we know if this had any measurable effects, positive or negative on the community of female players? That is much more difficult to judge.

Different people will weigh differently the balance of the outcomes. I do think that the most significant element here is the number of people that saw the post, and the number of people that liked it (which was also big).

But, even though I feel that so far we are on the positive side, let’s move on to the next step to see if this will offer us a different perspective.

Step 2: Deontological Principles

To apply Kant’s principles to this promotional post, we should ask:

- Would it be acceptable for all influencers to promote content in the same manner?

- Are the influencers respecting the autonomy, rights, and dignity of themselves and others?

- Are they treating themselves and their audience as ends in themselves, not merely as a means to gain followers or subscriptions?

Different people can argue about the answers to these questions. But, I accepted the risk of offering my point of view, so I’ll not back up now.

I will say that for the first two questions, it is a clear “yes” for me.

But, for the third question, it feels to me that the answer is that the influencers involved, seem to want to use their post as a way to gain paid subscriptions. The reason I think this observation is fair is that the message has 1 photo and 2 sentences. One of the sentences is about following the influencers on their FanHouse profile. This consists of 50% of the message they communicated.

If the message contained other elements, I would be less certain, but as things stand, I cannot but consider that the Kantian consideration makes this post fall somewhat on the negative side.

However, we still don’t have clarity. Let’s continue then to the next step.

Step 3: Social Norms and Traditions

For this step, this is what we should consider:

- Legal Framework. I do believe that there is nothing wrong here.

- Cultural Expectations. What are the cultural attitudes towards the portrayal of women in media and sports within the community where the content is being shared?

- Industry Practices. What are the common practices within the chess community and the broader field of influencer marketing? Does the content adhere to or deviate from these established practices?

The contractarian perspective doesn’t strongly oppose the influencers’ approach, although it’s unusual to see prominent female chess players in such attire. While this is more common in other sports, society today isn’t generally shocked by women in lingerie.

We’ll now consider the final step to see if it helps us reach a clearer conclusion.

Part 4: Personal Virtues and Values

For those who follow me on social media, you likely have an idea of the things that are important to me. I greatly value providing meaningful content to my audience, whether that’s sharing knowledge or practical advice. While I don’t oppose lighter, entertaining posts, I take issue with content that aims to draw attention to individuals solely based on their physical appearance rather than conveying a broader, positive message or highlighting a worthy cause.

“Girls do it better than Messi and Ronaldo” feels like a lost opportunity to me to highlight a bigger message about the multifaceted talents and creative power of women beyond just physical comparisons or objectification.

So, ultimately, this post left a bitter taste in my mouth, but I have to admit that when I analyzed this with the help of all the tools presented here, my opinion became less strong. The above tools forced me to see different angles, and even consider at some point changing my opinion from a negative, to a positive one (although, never strongly positive).

I hope that you were able to find the same exercise as useful and enlightening as it was for me.

Conclusion

That was a lengthy article covering many ethical concepts and examples. If you made it this far, congratulations!

As you saw, I personally lean more towards a consequentialist/utilitarian approach because “providing value” is one of my guiding principles. But I also recognize the importance of moral obligations, as well as how traditions significantly inform many people’s decisions.

Aristotle’s idea that shaping an ethical character is a constant, daily effort resonates with me. The tools examined here have helped me in this ongoing pursuit. Hopefully, they’ll aid you as well.

Lastly, I presented an amateur attempt to create a formula by combining core elements from different ethical theories into “Nikos Ethics.” I am not unhappy with what I came up with but don’t take that seriously. What you can do instead, is follow modern philosophers, and study their frameworks. Developing new approaches by synthesizing fundamental theories is central to modern ethics discussions.

See you on X, Facebook or LinkedIn when the next chess drama unfolds!

- And not only chess world

- Think of the typical chess Twitter fan. Or typical Twitter use, for that matter.

- Let’s not dive into this now, but that was a central part of study for centuries

- In philosophy, finding a consensus on anything is generally tough, especially in the field of Ethics. When philosophers reach a consensus, it is probably time to leave the details to scientists to figure out, and for philosophers to move on to another topic. Generally, philosophy operates in areas of human inquiry where consensus has not yet been reached. I can quote any introductory book on philosophy on this, but I’ll propose the amazing intro from AC Grayling’s “The History of Philosophy” where he explores this idea more deeply.

- For more about the role of emotions in Ethics, you can read about Emotivism here: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Emotivism or check the course “Introduction to Philosophy” from the University of Edinburgh in Coursera. It is not by chance that Emotivism is at a central place in the discussion about Ethics in Scotland, as David Hume, a Scottish Philosopher set the foundations of the theory. In this article, I’ll follow a more traditional approach and I’ll not examine Emotivism.

- But, don’t be too quick to dismiss these foundations; they are well-thought-out. Just as you cannot refute the Dragon Sicilian overnight, don’t expect to refute that easily what took giants of thought like Aristotle or Kant a lifetime to develop. There’s a reason people still study these theories (and people still play the Dragon). Both have something that speaks to the minds and hearts of those who study them.

- One example of this, is the “SBI” model on which many business managers and executives get trained. You can read about it here.

- Also, please note, that all the theories we will present, evolve to address their weaknesses (like consequentialist public policy theories accounting for the rights of minorities.

- The reason for this discussion on the subtle difference between consequentialism and utilitarianism, is to help those who will try to explore these ideas further on their own. The constant challenge when you read articles about ethics online is the use of terminology which can be a bit confusing and hard to digest at first.

- Do note that philosophers have been debating these questions for the last 250 years. So don’t worry if you don’t get it right in your first try

- A word of caution. In this article, when I mention real-life examples from the chess community, I will be greatly simplifying things. There might be legal implications which I don’t touch upon, as I am not an expert. So, take the analysis of these examples for what they are: a first, incomplete attempt to look at real examples through a specific lens.

- Although the number of people getting affected negatively – just like in the trolley problem – is an important parameter.

- For the geek among us that wants a deep dive into this debate, check out Plato’s dialogue “Euthyphro”. For a video presentation of this, you can check the excellent video from “Crash Course Philosophy” here.

- You can check Wikipedian’s article on “Thomism”

- Before we dive into Kant’s ideas, here’s an interesting tidbit about his life. Imagine if Kant had passed away before turning 50, we wouldn’t know his name today. He’s what you’d call a “late-bloomer.” Sometimes, people wrongly think that after reaching a certain age, there’s not much left to achieve. But Kant proves that’s not true. He’s a reminder that no matter our age – and I’m saying this as someone about to hit 40 – we can always make meaningful contributions.

- This is my personal attempt to phrase it simpler. The original states: “Act as if the maxims of your action were to become through your will a universal law of nature.”

- A variation of this is the so-called “Golden Rule”, which states “Don’t do to others what you don’t want them to do to you” or something along these lines. It is called a “Golden Rule” for many reasons. It is practical and easy to understand, and versions of it can be found in almost all cultures with recorded history. So, it has a global reach.

- Again, my attempt to simplify the original, which goes: “Act in such a way that you treat humanity, whether in your own person or in the person of any other, never merely as a means to an end, but always at the same time as an end.”

- If you still unclear what exactly this means, I can recommend a great article by one of my favourite authors, Mark Manson, on this topic – Vjeko.

- Possibly the first constructed argument in favor of doing this, can be found in Plato’s “Crito”. The main character of the book, Socrates, uses a social contract argument to explain to Crito why he must remain in prison and accept the death penalty, even though he was offered a chance to escape.

- Especially marketing and sales. If you read books on branding, communication, or influencer marketing, it is like reading an updated version of the teachings of Aristotle. Aristotle’s Framework “Ethos, Pathos, Logos”, which he described in his book “The Rhetoric“, still plays an important part in modern marketing, updated with scientific advancements in behavioral psychology.

- When we mention this, we’re usually thinking of three philosophers: Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle. They are connected in a lineage of mentor to pupil.

- However, this perspective shifted during the Roman Empire’s ascendancy. In contrast to ancient Greece’s democratic ethos, where citizens felt compelled to actively participate in governing their city-states (sadly, not ALL citizens, but that’s another discussion) and safeguard societal welfare as much as their own, the Roman era presented limited avenues for individuals to influence the political status quo. That’s why philosophical systems like Stoicism developed and flourished. Stoics focused on what one can control—namely, one’s own thoughts and actions—and accepting what one cannot control.

- He argued with his teacher Plato on this. Plato believed that the virtues are inside us, and we “discover” them.

Right now, there is a HUGE discussion, politically heated, on this (you may come across it as the “Blank State” or the “Tabula Rasa” hypothesis, although there are many more names).

- Aristotle calls this the doctrine of the mean in one of the most influential books on ethics of all times, the “Nicomachean Ethics”. He also says that the mean is relative to us, meaning that it depends on our circumstances and capacities.

- HBR for example, has a ton or articles (and books) on this. One example: https://hbr.org/2023/02/how-to-find-define-and-use-your-values

- As an example, these are the values we have defined in the company I work for: https://databox.com/how-were-bringing-databox-company-values-to-life

- Sticking to your values, helps you also build trust and allows others to know what to expect from you and understand where you are coming from.. I will not explore this topic further, but why and how you build trust, is an important part for personal and professional development. Just one of the thousands of good resources on that: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EFeEAtXdzFU

Very Useful and Honest Points are handled.Many Thanks