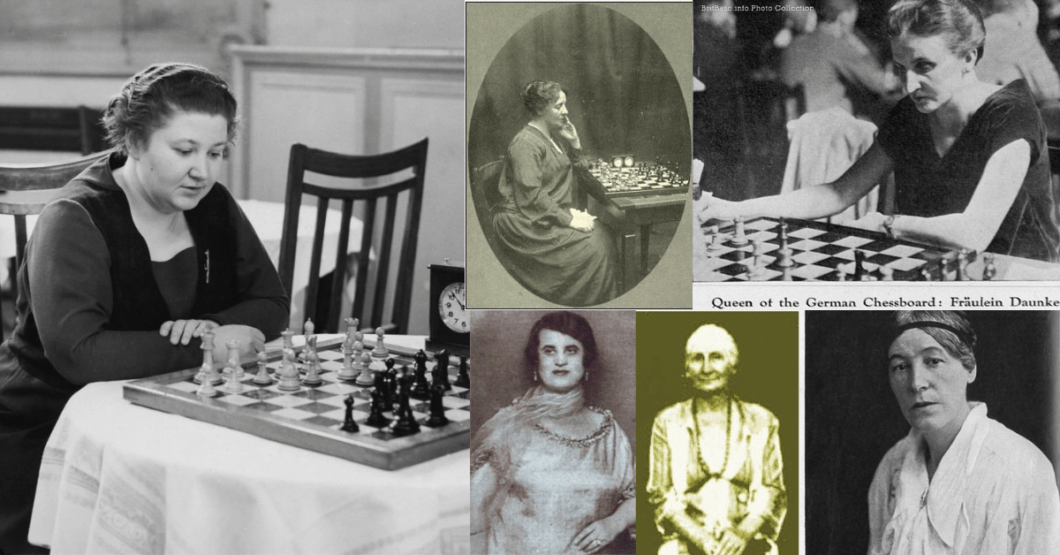

Cover Photo: Vera Menchik (Left), Paula Wolf-Kalmar, Wally Henschel (top), Katarina Beskow and Agnes Stevenson (bottom), Sources: Various, but mostly the fantastic website BritBase by John Saunders and the following Chessbase article

Women’s World Chess Championship 1930

Introduction

Three years after the inaugural edition of the Women’s World Chess Championship, the 2nd edition of the tournament was organized in 1930 – once again alongside the 3rd Chess Olympiad (or Tournament of Nations, as this event was called back in the day). The Olympiad itself – as well as the accompanying events were organized in Hamburg by the president of the Hamburg Chess Club and the German Chess Federation Walter Robinow in order to celebrate the centenary of the Hamburg Chess Club. 1

Walter Robinow. Source: https://www.schachbund.de/news/id-150-geburtstag-von-walter-robinow.html

Participants and format

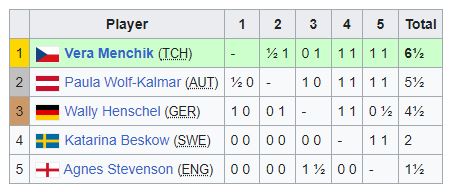

In contrast to the previous edition of the tournament which fielded 12 ladies – in the Women’s World Chess Championship 1930 there were only 5 competitors:

- Vera Menchik – the defending champion and the greatest female player of the first half of the 20th century

- Paula Wolf-Kalmar – third prize winner from 1927

- Wally Henschel – a German chess player and a debutant in this competition. Incidentally enough, just like Robinow – she would also later have to emigrate to the USA due to her Jewish origins

- Katarina Beskow – the 2nd prize winner in the 1927 Women’s World Chess Championship

- Agnes Stevenson – the only other British competitor, apart from Menchik

Due to the much fewer participants than in the previous edition, 2 the format of the tournament was double round-robin (all-play-all).

Games and results

The defending champion Vera Menchik was considered to be the undisputable pre-tournament favourite. Not only did she win the previous edition in a very dominant fashion – but in the subsequent three years she participated in a number of „Open“ tournaments – such as Paris 1929, Karlsbad 1929, and Hastings 1929/1930 – gaining a lot of experience in competing at the highest level.

Indeed, Menchik managed to justify these expectations and defend her title. However, the tournament path toward the title was anything but rosy.

In the first half, Vera drew with Paula Wolf-Kalmar and lost with White to the debutant Wally Henschel. It is hard to emphasize how big of an upset it was – should it suffice to say that this was Menchik’s only loss in all of her appearances in the Women’s World Chess Championships 3 Needless to say, we should take a look at this game 4:

Note: The games are available for free in the following lichess study and can also be downloaded for free (together with many others) on my “Free PGN Downloads” page

Even after enduring such a shock, Menchik managed to retain her composure and continued winning all her other games. By the 2nd half of the tournament, she was very much in the race for first place and her 2nd game against Paula Kalmar-Wolf turned out to be the one to ultimately decide the champion

style=”text-align: justify;”>It has to be said I was unable to figure out in which round the game was played and how many points the players had. In his book Vera Menchik: A Biography of the First Women’s World Chess Champion, R.B. Tanner stated that:

„Shortly thereafter Paula also lost to Wally Henschel and Menchik won her second title“

But given that Wolf-Kalmar finished a clear point behind, I hope it is not a big historical mishap to say that this game decided the tournament. 5

Thus, with the final score of 6.5/8, Vera Menchik managed to defend her title and reinforce her status as the strongest female player of the time!

References and Further Reading

http://www.olimpbase.org/1930/1930in.html

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Walter_Robinow

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wally_Henschel

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/3rd_Chess_Olympiad

- Interestingly enough, Robinow would have to resign from these posts 3 years later when Nazis came to power due to his Jewish origins

- which was presumably due to the fact that the majority of the strong chess-playing women at a time resided in the UK

- Without including her match against Sonja Graf in 1937

- Not only because it is such a historic game – but also because it is one of the only three (!!) games whose scores have been preserved to this day.

- This whole „lack of information“ thing is just one of the examples of how female chess has been mistreated throughout its history. I hope that one day some enthusiastic chess historian will fill in these „blanks“ in the history of our game.

Interesting article.

How big, would you say, is the difference in chess ability between male and female players back then compared to now?

In my opinion, there are many sides to it. For starters, chess is a very ancient game, so generations pick up where previous generations left off — learning from their shortcomings and building on top of their experience. The fact that chess has been viewed as a male game for a very long time means that male players today naturally have so much more of that chess “heritage”.

On the other hand, with the chess supercomputers available today, the role of preparation and theory knowledge is immensely larger, so one may argue that the gap is nowhere near as big as it used to be.

There’s also a lot more media coverage nowadays, so I’m sure that has a role to play.

I’d love to know what you think.